Ephrem Kossaify

NEW YORK CITY: On Sept.11, 2001, the recently inaugurated President George W. Bush suddenly found himself a wartime president.

“Today, our nation saw evil,” he declared in a calm, composed speech from the White House. Thanking the world for its outpouring support, Bush said “America and its allies stand together to win the war against terrorism.”

Any nation that harbors terrorist groups was now considered a hostile regime, Bush declared. Before a joint session of Congress, he announced a new approach to foreign policy: “Our war on terror begins with Al-Qaeda, but it does not end there. It will not end until every terrorist group of global reach has been found, stopped and defeated.”

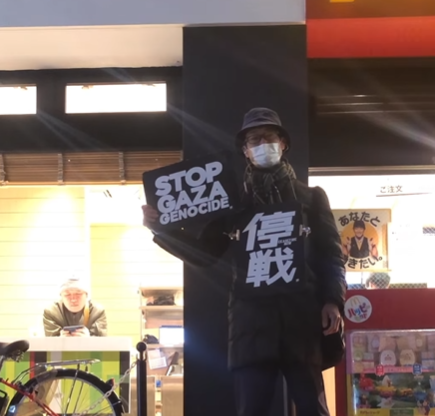

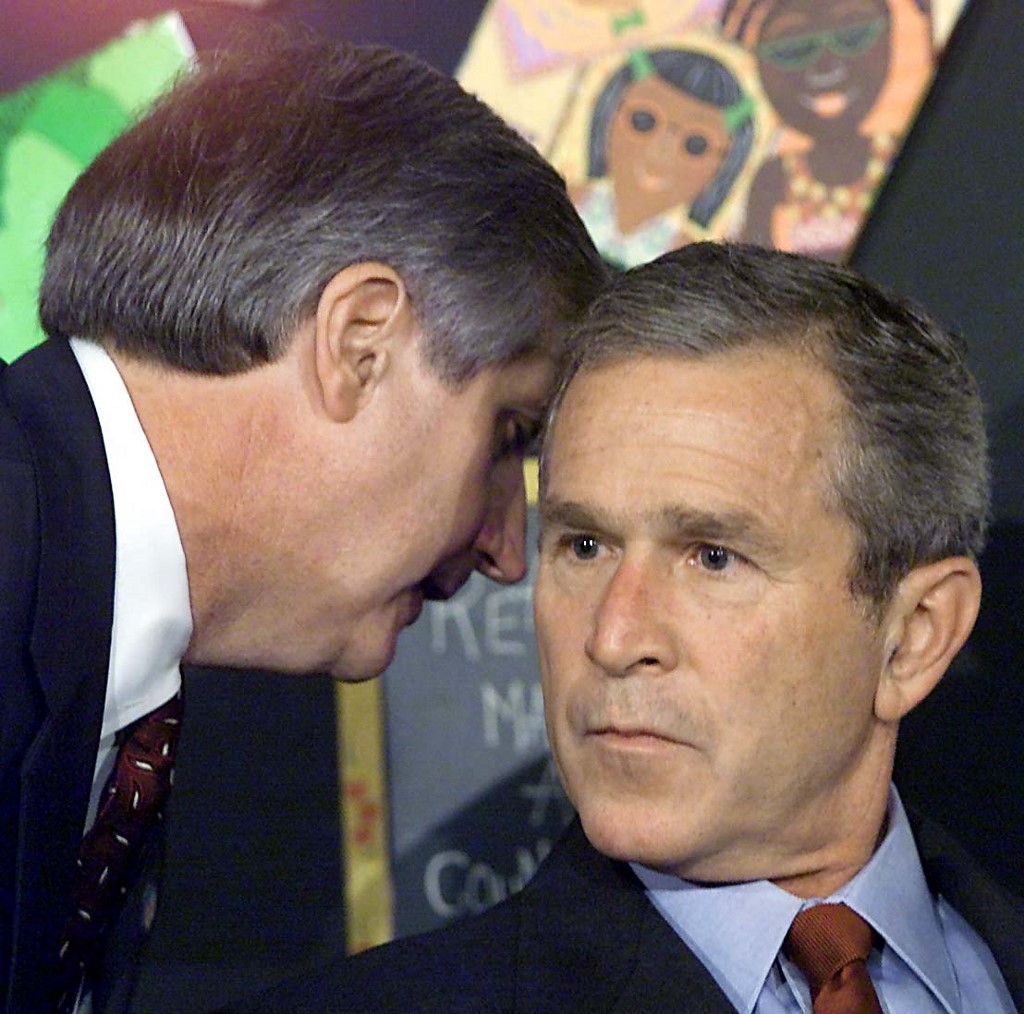

In this photo released by The White House 16 September, 2001, US President George W. Bush (R) speaks to his staff 11 September, 2001. (File/AFP)

The post 9/11 era of American history had thus begun, and for the next two decades achieving victory in the “war on terror” took center stage. In the aftermath of the attacks, Americans feared that the enemy who had perpetrated the carnage would escape punishment.

A bullseye was thus drawn on Al-Qaeda. Osama bin Laden was identified by federal authorities as a prime suspect, believed to be under the protection of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan. Bush demanded the Taliban hand over Bin Laden and all other leaders of Al-Qaeda or share in their fate. The Taliban refused.

A frame grab (L) taken 29 October 2004 from a videotape aired by Al-Jazeera news channel shows Al-Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden. (File/AFP)

Bush then signed into law a joint resolution by Congress authorizing the use of force against the perpetrators of the 9/11 attacks.

The resolution would later be cited at various occasions by the Bush administration as a legal basis for measures to combat terrorism: From invading Afghanistan and Iraq, to expanding government surveillance power, to building the detention camp at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba.

Marines from Gun Team Two of the 11th Marine Expeditionary Unit prepare to fire at targets down range during artillery direct fire training in late August 2002. (File/AFP)

On Oct. 7, 2001, the Afghan war, branded “Operation Enduring Freedom,” began. US and British airstrikes targeted Al-Qaeda and Taliban fighters, while most of the ground combat was later conducted between the Taliban and their Afghan opponents, the Northern Alliance and ethnic Pashtun forces.

Two years later, in 2003, while approximately 8,000 American troops remained as part of the International Security Assistance Force overseen by NATO, US Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld declared major combat operations had come to an end in Afghanistan.

A US Air Force Chaplain identified only as “Fred” leads US Air Force crew members from Charleston, South Carolina, in prayer prior to takeoff 18 October, 2001. (File/AFP)

Almost simultaneously, America was getting ready for another war.

In a State of the Union address, Bush had called out an “Axis of Evil” consisting of North Korea, Iran and Iraq. He declared them all a threat to American security. And on March 20, 2003, he announced that US forces had begun military operations in Iraq, vowing to destroy Saddam Hussain’s weapons of mass destruction along with his dictatorial rule.

The initial effort to decapitate Iraq’s leadership with air strikes failed, clearing the way for a ground invasion.

Less than two months later, on May 1, 2003, Bush declared the end of major combat operations in Iraq from the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Abraham Lincoln, emblazoned with a giant sign that read: Mission Accomplished.

Rumsfeld dismissed lawlessness and skirmishes in the country as the desperate acts of “dead-enders.”

Saddam Hussain’s army was disbanded. He was captured, tried and hanged. Democratic elections were held.

Photo dated 11 September 2001 shows US President George W. Bush (R) being informed by his chief of staff Andrew Card of the attacks in New York. (File/AFP)

Meanwhile, 100,000 Iraqi civilians were killed along with over 5,000 US and allied troops. With the US fighting a war in Iraq, the Taliban, who were initially defeated in Afghanistan, regrouped, and their attacks escalated, keeping the war raging for 20 years, killing tens of thousands and displacing millions.

As for the elusive Bin Laden, he evaded capture until May 2, 2011, during the Obama presidency. His demise came during a raid by a US Navy SEAL team in his hideout in Pakistan.

This summer, when foreign forces announced their withdrawal following a deal between the US and the Taliban, the latter launched offensives and began a rapid advance across the country, capturing the capital Kabul on Aug. 15.

Harvard Kennedy School estimated that the total cost of the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq was up to $6 trillion, making them the most expensive wars in US history.

The estimated average cost of deploying just one US soldier in Afghanistan was over $1 million a year, at a cost of approximately $4,000 per taxpayer.

In parallel with two wars overseas, the war on terror was also being waged on American soil where a reorganizing of the security state was launched.

On Nov. 13, 2001, Bush signed an order that established military tribunals to try non-US citizens affiliated with Al-Qaeda or involved in any terrorist activity. His administration held the accused terrorists at Guantanamo, where the legality of the detentions could not be challenged.

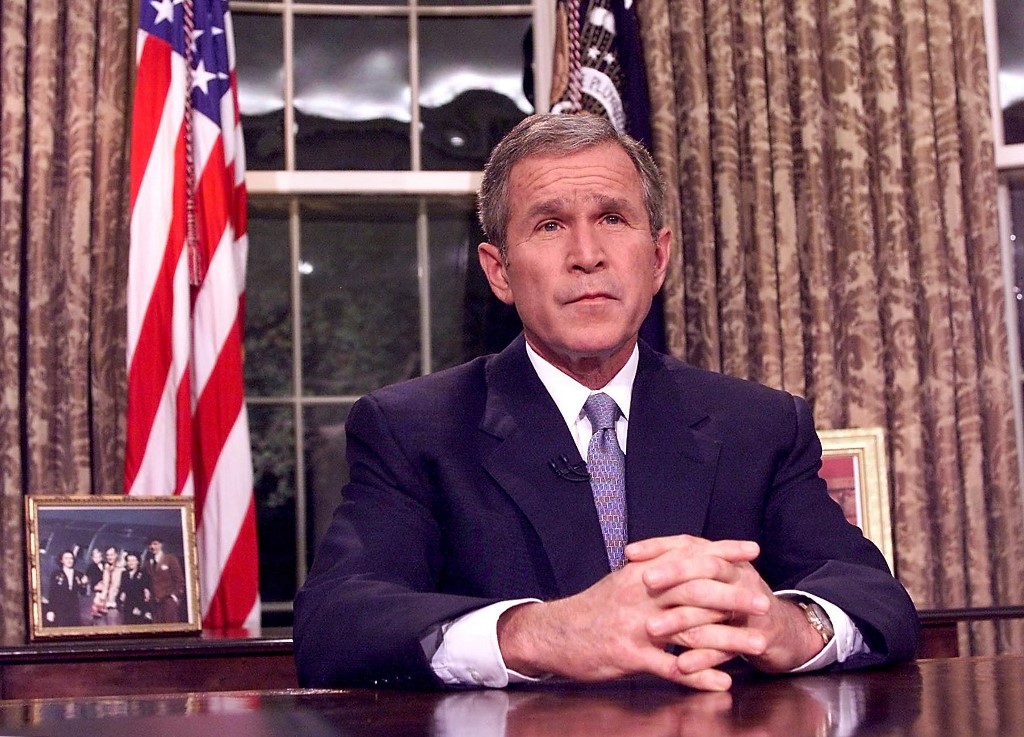

US President George W. Bush addresses the nation from the Oval Office 11 September, 2001 at the White House in Washington, DC. (File/AFP)

The initial 158 detainees were designated as enemy combatants which placed them outside the protections of the Geneva Convention.

“Enhanced interrogation methods” at Guantanamo included sleep deprivation and waterboarding. There was much debate in the US about the legality, the quality of information that prisoners might surrender under duress, and the ethics of such methods, which critics said amounted to torture.

Later in 2004, when photographs emerged of prisoners being abused in the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq, it led to intense worldwide scrutiny of US policies.

Family members and friends of the victims of the 11 September 2001 attacks gather around a memorial circle at the “Ground Zero” site on 11 September 2002 in New York. (File/AFP)

Meanwhile, Arab Americans, South Asians and Muslims in general became an instant target for attacks, threats, verbal abuse and harassment across the country.

Molotov cocktails were thrown into Pakistani mosques, assault rifles were fired at businesses belonging to Yemenis, and traumatized Kuwaiti students sought mental counseling at their embassy in Washington.

The politically charged term “Islamophobia” entered the American lexicon.

Bush urged people not to take vengeance. “Our nation must be mindful that there are thousands of Arab Americans that live in New York City who love the flag just as much,” he said.

US President George W. Bush (R), his wife Laura (C), National Security Advisor Condoleezza Rice (L) observe a moment of silence 11 September, 2002 at the White House in Washington, DC. (File/AFP)

Two controversial government actions were blamed for years of harassment of the vulnerable communities while also sparking outrage from average Americans who feared the loss of basic civil liberties and ideals upon which their country was built.

A mere 10 days after 9/11, as his administration faced tough questions over what clues various agencies had missed about the imminent attacks, Bush announced the creation of a new umbrella office to oversee domestic security.

No fewer than 22 agencies were then absorbed into the new Department of Homeland Security. DHS’s missions included counterterrorism programs, recovery from natural disasters, protecting and regulating the US border, and defending the nation from cyberattack.

Caption

The name “homeland” alone was a problem for many. Rumsfeld himself once said “homeland defense” sounded more German than American. “It smacks of isolationism, which I am uncomfortable with.”

DHS also absorbed the entire Immigration and Naturalization Service, moving its functions into the Immigration and Customs Enforcement. Of all the agencies within DHS, perhaps none has attracted so much contempt as ICE.

Every year since 2001, ICE has detained hundreds of thousands of people without criminal records. That figure jumped by 40 percent during the Trump presidency.

ICE agents have carried out arrest operations at courthouses, hospitals and even schools where targets were dropping off their children. An example includes the arrest of Syed Jamal in Kansas on his front lawn while he was getting his children ready for school.

The most vibrant city on earth fell briefly silent 11 September 2002 as New Yorkers remembered with tears, anger and defiance the that an unimaginable act of extremism shattered their lives. (File/AFP)

Jamal was a chemistry teacher who had lived in the US for 30 years and had no criminal record.

Many have since made the case for abolishing DHS as “wasteful, incompetent and abusive mega-agency,” with Republican Senator Tom Coburn of Oklahoma, who served on the Senate Homeland Security Committee, declaring at the end of his tenure that “DHS’s main domestic counterterrorism programs are yielding little value for the nation’s counterterrorism efforts.”

Prior to the existence of DHS, another symbol of the expansion of government surveillance powers was the USA Patriot Act, also overwhelmingly passed by Congress just weeks after 9/11, which gave the government a range of new powers including provisions that made it much easier to collect communications records and interrogate anyone it suspected of terrorism.

A hijacked commercial plane crashes into the World Trade Center 11 September 2001 in New York. (File/AFP)

A review by the government’s Privacy and Civil Liberties Oversight Board said: “We have not identified a single instance involving a threat to the US in which the telephone records program made a concrete difference in the outcome of a counterterrorism investigation.”

The Obama administration said that the Act had been “extremely helpful” in terrorism investigations.

Twitter: @EphremKossaify