Nader Sammouri

OSAKA: What is the noblest thing an architect or a designer can do? It is probably designing for the ones who are most in need.

When a natural disaster strikes, the majority of people flee away from the tragedy zone. However, Shigeru Ban heads towards it.

It is hard to meet a person like Shigeru Ban and not be left wondering about higher life purposes. Meaning in life came to Ban after noticing that architecture is not serving the purpose it is supposed to.

Power and money are invisible. Throughout history and up until now, architecture has been rendered as a display for both. Architects and designers gravitate towards delivering high-end, luxurious and aesthetically pleasing projects. They utilize their creative talents to serve privileged people and hop between prestigious commissions, disregarding people who need their skills the most.

“Any architect can be influenced by popular culture, and many international architects do, but I don’t want to be influenced by the fashionable style of the time,” Ban said.

Ban doesn’t want to mirror the transient trends in his work and wants to emerge from his own set of values.

“I found out that the few architects who weren’t influenced by the style of the time were Buckminster Fuller and Frei Otto. Those two invented their own structural system and texture approach, and I wanted to develop my own as well. I found my style in paper, or to be more exact, cardboard tube structures,” Ban told Arab News Japan.

Stepping into a Paper Office

Ban’s Tokyo office meeting room has a dozen of chairs made of paper tubes, which could not be more apt when considering that he is a master of paper architecture. Ban initiated the discussion humbly by disregarding his successes and articulating how many of his projects were never realized in the Middle East. He also added how he lost various competitions in Lebanon and the UAE, like the Sheikh Zayed’s museum competition where he used sand as a building material.

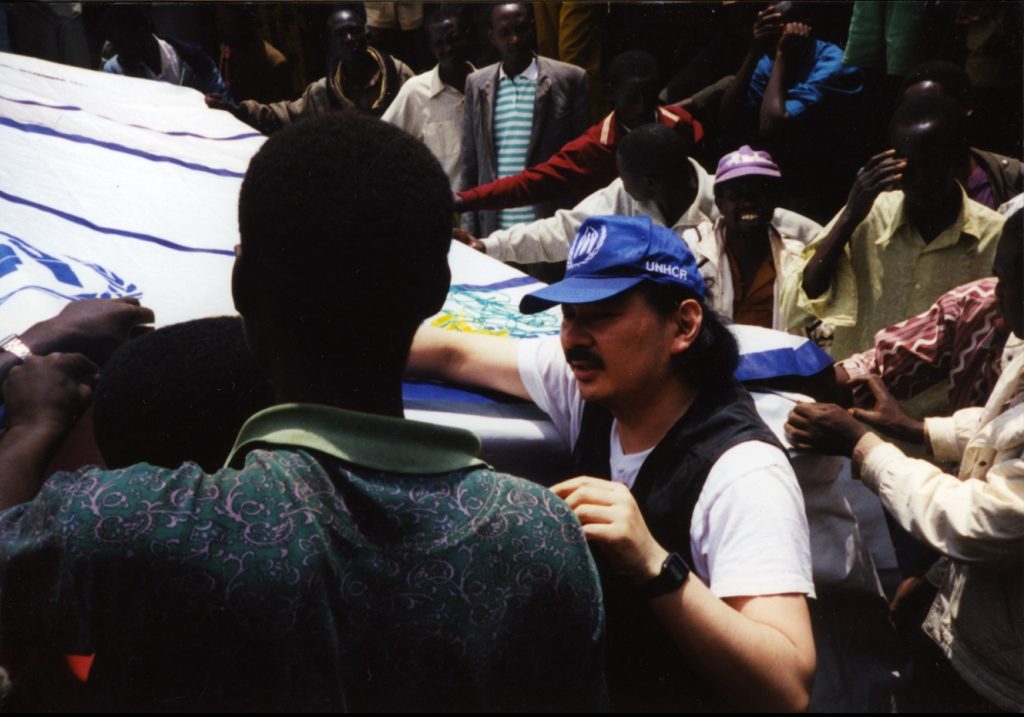

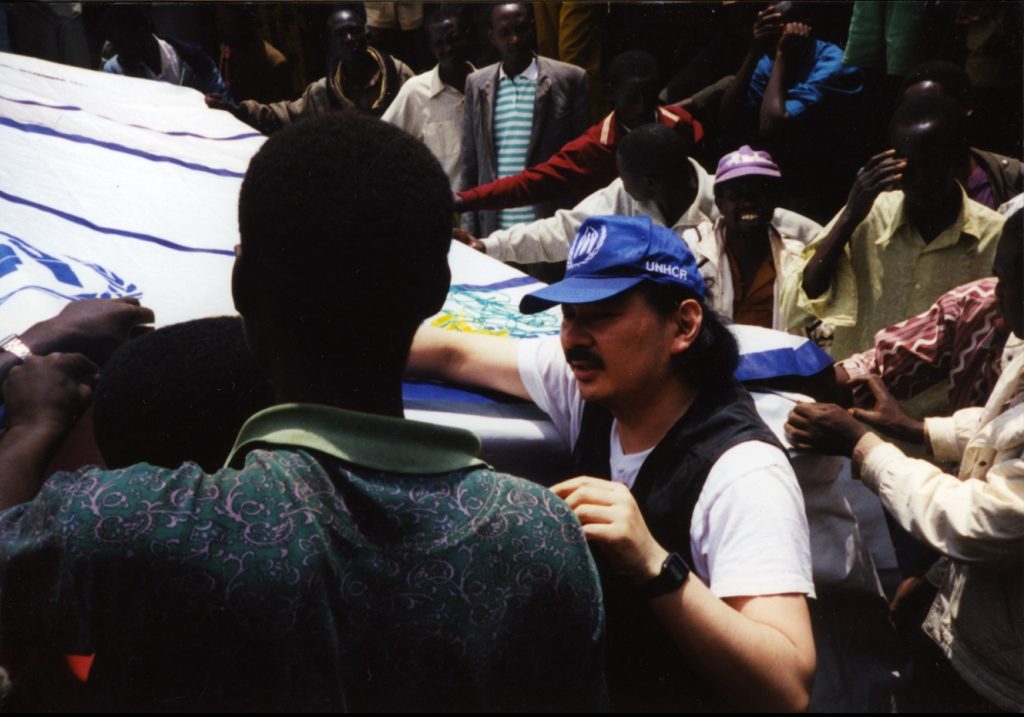

When a devastating earthquake hit Izmit in Turkey in 1999, almost 500,000 people became homeless. Ban stepped in to contribute to disaster-relief of the area by constructing the iconic paper log house. He did similar projects for post-disasters in Japan, Ecuador, India, China, Rwanda, Kenya, Sri Lanka, Italy, and more. Because of the project requirement, many of Ban’s architecture was almost occasional and stood temporarily until they served their purpose.

Ban is a Japanese architect who is well-recognized for his experimental use of unusual building materials and innovation, in particular waterproof and fireproof recycled paper-tube structures.

His compassionate approach to design touched a largely disregarded segment of society, and his commitment to humanity granted him the most prestigious prize in modern architecture in 2014, the Pritzker Architecture Award.

Read more: A world redrawn: Japan architect Ban urges virus-safe shelters

An Inflection Point

In 2003, Ban won an international competition to design Pompidou Center-Metz in France, a contemporary art center, an inflection point which he declared to have changed his life.

“Winning the competition for Pompidou Center-Metz changed my life because from there, I created my office in Paris and started commuting weekly between Tokyo and Paris,” Ban said.

Ban made his own cardboard studio on the top of the Centre Pompidou in Paris and worked there for 6 years. He jokingly mentioned how friends who visited him had to buy a museum ticket to see him.

The Permanence of “Temporary” Structures

Ban introduces a new perspective, questioning that a building’s strength and durability have nothing to do with the strength of the material. He said that if a timber building is structurally well-designed, it cannot be destroyed by an earthquake as opposed to many concrete structures, which an earthquake can quickly destroy.

“Even cardboard tubes, though weaker than wood, can be a good structural material for durable buildings. I realized that logically, and I just needed to prove it through testing. We tested cardboard many times to understand its characteristics so that we can design a structure because building safety is the most important,” Ban explained.

Ban started building temporary structures little by little, bigger and better, learning after every experience until he started making permanent paper buildings.

Ban questions that if a temporary building survives decades, then what is temporary and what is permanent?

“Even a concrete building is temporary if the building is made to make money. The high-rise Grand Prince Hotel Akasaka, designed by the famous Kenzo Tange, was demolished in less than 30 years and replaced by a new one. On the other hand, some of my temporary structures that are made with paper like the paper church in Kobe city was used for ten years since 1995, and then disassembled and moved to Taiwan after an earthquake and became permanent and standing until today,” Ban explained and added, “So what is permanent and what is temporary doesn’t depend on the material but whether people love the building or not.”

“I don’t believe paper is good for high-rise buildings, but what is more important for emphasis is that I don’t believe we need high-rise buildings anymore. Those don’t exist out of necessity, but out of people’s desire to build individual or corporate symbols or, in other words, identities to exhibit authority,” Ban thought.

Mobile Architecture

Ban predicts that we may change our way of work and living quite often in the future. Therefore buildings don’t need to be permanent. On that basis, we should make our facilities mobile, and compared to concrete which we use pretty often, steel and timber are suitable building materials for that mobility that we require.

“I don’t imagine a mobile future with concrete buildings being a part of it. Concrete isn’t recyclable, creates a lot of CO2, and takes too long to construct. Steel and timber are ideal as long as the building is not high. My biggest interest presently and what I like to realize in the future is the moving city project or mobile architecture,” Ban declared and continued saying:

“I am currently doing some research regarding mobility and moving capitals. At the end of the 90s, the Japanese government decided to move its capital outside of Tokyo and elected three cities, but then gave up because they couldn’t finalize a decision. Australia, Brazil, and Myanmar moved their capitals in earlier times, and Indonesia is planning to do so as well,” Ban said.

He added that although moving a capital is an excellent chance to rejuvenate different areas of the country, it isn’t realistic anymore because of the loss of natural fields that it requires. Nevertheless, moving parts of capital functions, like the parliament building to different cities every 4-5 years, could be feasible.

Ban compared the latter to Olympic events, saying:

“The Olympics is interesting in the way that best athletes meet. It is like in the parliament where chosen politicians from each city gather in one of the cities, so as long as transportation is decent, the parliament can be anywhere.”

A Message to Beirut

“I think it is good to have small-sized earthquakes to release the tension of earth gradually and to expose weak buildings before big earthquakes occur. Also, to inform us which buildings need be reinforced or rebuilt to avoid maximum injuries,” Ban said and elaborated that earthquakes could even destroy bulky buildings if they aren’t feasible.

Ban believes that earthquakes never kill people, but concrete does. On the other hand, cardboard and wood can stand up against earthquake vibrations.

Ban brought up the August 5 port incident in Beirut to the discussion with a positive outlook saying that “these big kinds of disasters give us the chance to change. After the 2011 Tohoku earthquake in Japan, the Japanese government only built a wall between the sea and land and disconnected nature with what I thought was a big mistake. We should have learned better. Disasters can be opportunities to improve something.”

Ban expressed his love to Beirut while he was smiling, saying:

“I love Beirut so much. It is such a beautiful city. I love its culture because it has a natural mixture between local traditions and western culture and has gone through many natural layers of change. I think that makes a city very charming.”

“One of the solutions for refugees in Lebanon or its nearby countries can be something similar to what we do in Japan. When disasters occur here, people usually evacuate under a big roof, a gymnasium, or a basketball court. If refugees can be provided with one big tent with separate spaces inside it, it becomes easier to shelter people while giving them privacy. Food supply is better controlled when refugees are housed under one big tent. Putting them in separate tents makes it problematic, and individual tents aren’t strong enough in the wind,” Ban said.

When a crisis happens, many people look for ways to help out but don’t know where to start. One of the reasons is that they may lack good leaders of positive change.

“I go to the disaster field and form a team to lead with a plan in mind. Usually, I contact students from local universities that are close to the disaster field. For example, when a flood happened last July in Kumamoto, Japan, I contacted Kumamoto University to seek the help of the local students there,” Ban explained.

Ban also expressed the lack of order that he sometimes finds when he visits evacuation facilities when some families add partitions little by little to extend their space.

“When there is no particular system, refugees start to expand the boundary of their private spaces however they like. By creating a particular system, it is like we are forming a small city inside the gymnasium, with certain room boundaries,” Ban clarified.