- ARAB NEWS

- 14 Jul 2025

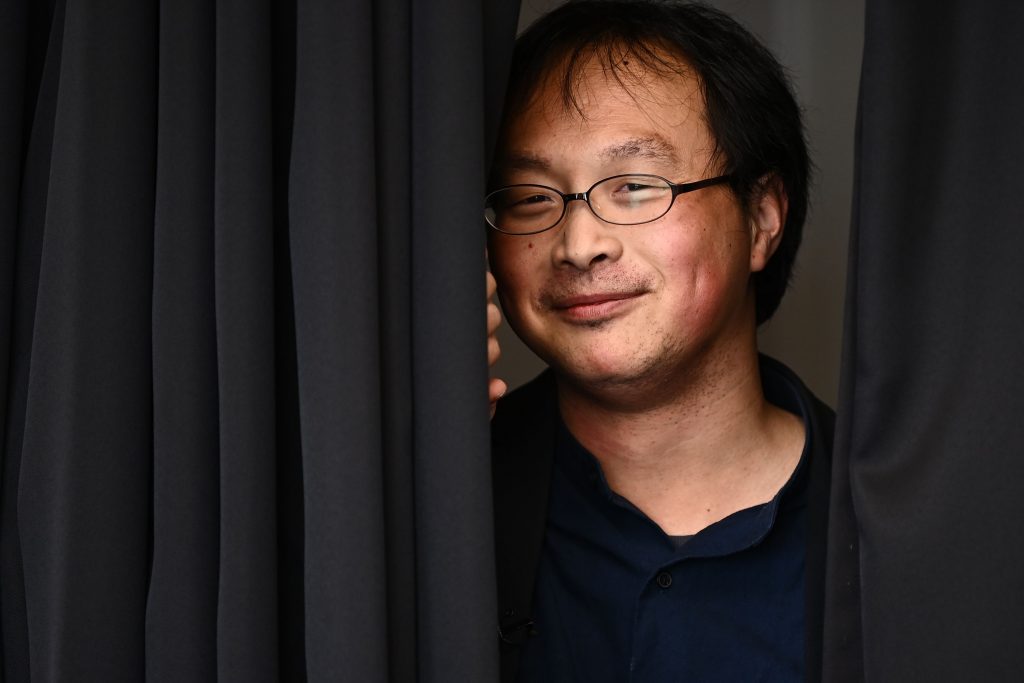

TOKYO: Japanese cinema needs an overhaul. At least that’s what acclaimed director Koji Fukada thinks, calling for less reliance on manga adaptations, more money for arthouse and better treatment of workers.

The 40-year-old’s latest film “The Real Thing” was chosen for the main selection at this year’s Cannes film festival, four years after he won a jury prize for emerging talent.

The glitzy French gathering was scrapped this year because of the coronavirus, but that has given Fukada more time to reflect on his concerns about the film industry at home.

Among them is what he sees as an over-reliance on adapting popular graphic novels rather than commissioning original ideas, he told AFP in an interview.

He is not opposed to manga adaptations — his latest movie is one — but he warns that the genre’s ubiquity has “a negative effect on diversity”.

“It’s difficult to produce non-commercial films in Japan, where a lot of importance is given to their marketability,” he said.

Japan’s film industry long found the greatest international success through its animated output, most famously those produced by the multi-award-winning Studio Ghibli.

That trend has shifted in recent years, however, with Hirokazu Kore-eda’s 2018 drama “Shoplifters” — the story of an impoverished family forced into crime to survive — nominated for the Best Foreign Film category in the Oscars last year.

But the country offers no government funds for arthouse movies, and studios prefer to minimise risk by backing what they see as sure-fire hits.

“At this rate, Japanese cinema is going to go down the drain,” Fukada warned.

He has made around a dozen films, ranging from his 2010 hit comedy-drama “Hospitalite” to 2016’s award-winning “Harmonium”.

They tackle subjects from xenophobia and loneliness to regret and revenge, subtly revealing secrets and lies hidden within families.

But in recent months he has turned to activism, launching a crowdfunding campaign for arthouse cinemas in Japan, which he said were “in danger of extinction” even before the pandemic.

“They are often owned by people who barely earn any money and are only motivated by their love of film,” he said.

“It’s not sustainable. We have to come up with a funding system that can withstand a second, or third wave of coronavirus.”

So far, his campaign with fellow director Ryusuke Hamaguchi has raised more than 330 million yen ($3.1 million).

He has also sought to raise awareness of working conditions in Japanese cinema.

“Some directors think that making a film is a battle,” he said, describing having been punched, kicked and insulted when he started his career.

While the #MeToo movement and associated calls for better treatment have made their mark on Hollywood and other film industries around the world, Japan still offers “a hostile climate” for those who call out harassment, according to Fukada.

A selection of his work will be screened as part of a special showcase at this year’s Tokyo International Film Festival, which kicks off on October 31.

“In the era of coronavirus, we thought that the public should have the chance to review his films,” festival director Kohei Ando told AFP, praising Fukada’s “critical eye on society and its absurdities.”

His films often confront themes of isolation — now in sharp focus as people are forced to stay home during the pandemic.

Fukada said he has paid close attention to the devastating effect the pandemic has had on society, noting a rise in suicides in Japan in recent months.

“Our everyday life, the things that we cherished, our loved ones, have been taken from us in one swoop,” he said.

His work, he said, tries to address universal subjects — including loneliness.

“It is in every one of us, and we try to live with it, to put a lid on it,” he said.

“But there is always a moment where it re-emerges, and forces us to ask ourselves about the meaning of life.”

AFP