LONDON: At first glance, the description of a new exhibition and accompanying book celebrating a decade of the British Museum collecting contemporary art of the Middle East and North Africa appears unnecessarily cumbersome, if not evasive.

The exhibition “Reflections: Contemporary art of the Middle East and North Africa,” writes Venetia Porter, the museum’s curator of Islamic and contemporary Middle East art, is “about a collection of works in the British Museum … made by artists born in or connected to countries that include Iran, Turkey, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia, Egypt and Tunisia, states that belong within the region known today as the Middle East and North Africa.”

In fact, far from being evasive, Porter is exercising precision, and mounting a challenge to what she sees as the frequently misused term “Islamic art,” and the perception in the West that there is only a single narrative at play in a region rich with a vast diversity of cultures, histories and current concerns.

“There’s a lot of misunderstanding about what this material from the modern and contemporary era is,” said Porter as the museum put the finishing touches to an exhibition that was due to open on Feb. 11 but which, thanks to COVID-19 restrictions, will now be launched only virtually.

“Some people will call it contemporary or modern Islamic art and I have issues about that. For a start the term ‘Islamic art’ is very complicated. It was created by western scholars and to a certain extent we are stuck with that now.”

But it is, she says, a “very reductive,” or simplistic term, and “the modern and contemporary art from this wide region is something that is so far removed from that description.”

Talking about Middle Eastern or North African art, she admits, “isn’t perfect either, although I feel it just gives it a bit more flexibility.”

But in the future, she says, “perhaps we shan’t have to use these terms at all.” One day, perhaps, “we will be able to talk just about ‘art’.”

This is not the first time the concept of modern and contemporary “Islamic art” has come in for robust scrutiny. In 2006 New York’s Museum of Modern Art staged “Without Boundary: Seventeen Ways of Looking,” an exhibition of 17 artists of diverse nationalities “who explore contemporary responses to Islamic art while also posing questions about issues of identity and spirituality” and who “work outside the expectations suggested by the term ‘Islamic art’.”

For MOMA curator Fereshteh Daftari, to describe the creativity of a region that stretched from the west coast of Africa to Indonesia as “Islamic art” was equivalent to “calling the art of the entire Western hemisphere ‘contemporary Christian art’.”

Porter could not agree more. The problem with the term “Islamic art,” as she writes in the foreword to the book accompanying the exhibition, is that it “perpetuates notions of a single identity, implying a unity within the vast output of production from across this slice of geography.”

In fact, she says, there are multiple narratives at play, as both the book and the collection of art from the region that she and the British Museum have built up over the past ten years demonstrate graphically.

A great deal of the importance and veracity of the British Museum’s collection stems from the guidance offered by the members of its Contemporary and Modern Middle Eastern Art group (CaMMEA), a body of patrons and art collectors whose views — and donations — have played a key part in the selection of works collected by Dr Porter and the museum since 2009.

The book’s preface is written by London-based art collector and philanthropist Dounia Nadar, whose husband Sherif Nadar, the founder and CEO of asset management company Horizon Asset, is also a member of CaMMEA. It was Mrs. Nadar’s meeting with Porter at the British Museum’s 2006 exhibition “Word into Art: Artists of The Middle East” that led to the formation of the group in 2009.

The list of members who have supported CaMMEA since 2009, recorded in the acknowledgments at the end of the book, reads like a Who’s Who of wealthy art lovers from or connected to the region. They include Sheikh Zayed bin Sultan bin Khalifa Al-Nahyan, grandson of Sheikh Khalifa, the president of the UAE; arts patron Sara Alireza, a member of the Saudi Art Council; and the British-Iranian art collector Mohammed Afkhami, the founder of Dubai-based financial consultancy MA Partners DMCC.

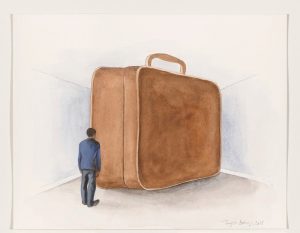

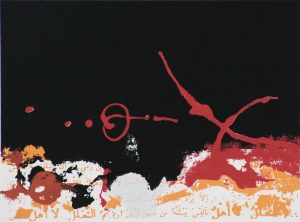

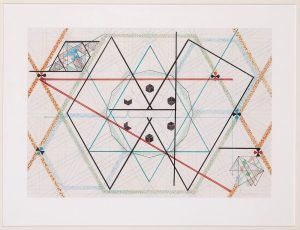

The works going on show, most of which have been acquired with the collaboration of the museum’s CaMMEA supporters, demonstrate that the art from or related to the region, and the experiences of the people who call it home or whose lives are rooted there, are hugely diverse.

There are, says Porter, “ideas about poetry, music and war. Some of these works also examine traditions of Islamic art — such as calligraphy or miniature painting – or even turn them on their head,” while “others narrate personal stories, highlight taboos, convey expressions of faith or nostalgia, and evoke exile.”

But “as we dig deep into what lies behind the image, however, and as the multiple histories of the region are seen through the prism of personal experience, that reflection becomes refracted: there is no one narrative but a multiplicity of stories.”

Porter has made enough contemporary artists from the region to know that few choose to be “pigeonholed” by the term “Islamic art … which is why I don’t use it at all in the book or the exhibition, except to set out the argument.

“You will have some artists who may consider themselves to be deeply religious and continuing an Islamic art tradition, but I want to hear it from them first before I actually put that label on them.”

The exhibition testifies to the right of any artist to represent any aspect of the human condition as they see fit, without having their art stifled by the expectations of artificial categorization.

For example, “Nu,” a gouache and charcoal drawn in 1969 work by the Lebanese artist Shafic Abboud, who died in 2004, is a figurative work that owes more to his training and life in Paris than it does to any overt Islamic influence.

By contrast “Le Bouna,” an earlier work by the same artist, evokes a folk tale told to him by his grandmother in the village of Mhaidse, northeast of Beirut, where Abboud spent much of his childhood.

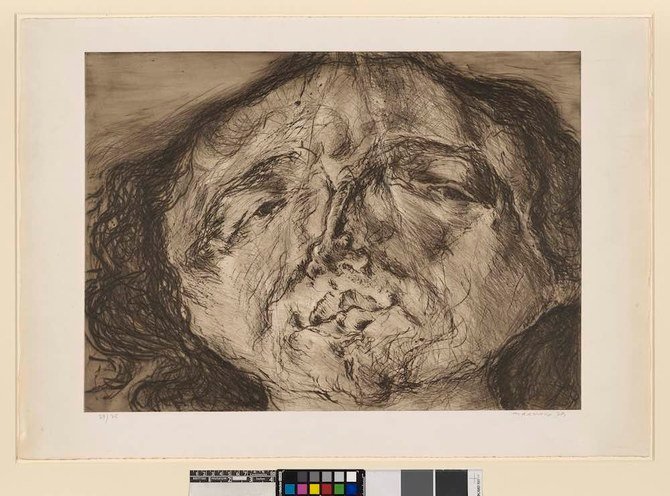

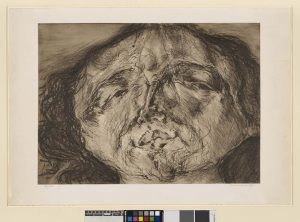

The exhibition opens with “The Accident,” a 2013 ink drawing by the Iranian-born artist Nicky Nodjoumi, which draws on his own experience of being interrogated by Iran’s secret police in the 1970s upon his return to the country from studying in New York. This work, says the British Museum, “challenges preconceptions about Middle Eastern art and highlights the complexities of being an artist in diaspora.”

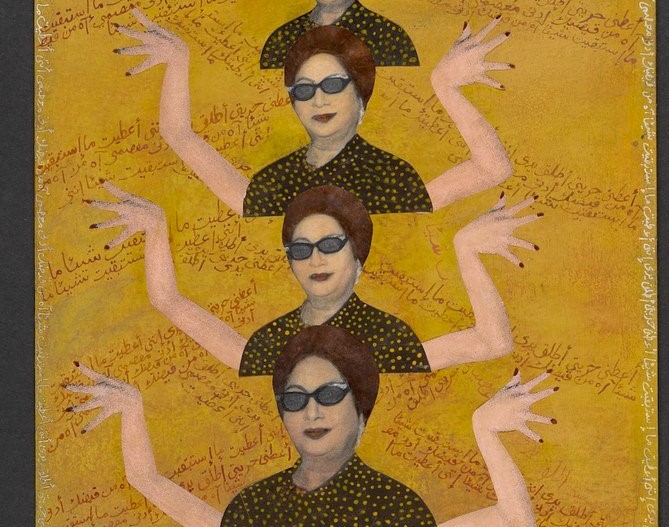

The Cairo-born Huda Lutfi’s striking “Al-Sitt and her Sunglasses,” on one level a paint-and-collage portrait of the singer Umm Kulthum, includes a handwritten verse from Al-Atlal (The Ruins), by the Egyptian poet Ibrahim Naji, and is part of a body of work that is “rich in allusions to, as well as criticism of, the cultural and political concerns of contemporary Egyptian society.”

Perhaps the most resonant work in the exhibition, highlighting “one of the defining issues of our time,” is “Natreen” (We Are Waiting), a 2013 portrait by the Moroccan-French photographer Leila Alaoui of Syrian refugees attempting to flee the terror of their bitterly divided home country.

To Alaoui, who was brought up in Marrakesh, “the subject of migration and its humanitarian consequences was of paramount interest.” She was killed in 2016, aged 23, in a terrorist attack in Burkina Faso while working on a photographic project about women’s rights for the charity Amnesty International.

——————-

Twitter: @JonathanGornall