- ARAB NEWS

- 14 Jul 2025

Deema Al-Khudair

JEDDAH: Storytellers across the Kingdom have received massive support in recent years, and the rewards are being shown on big screens near you.

The Red Sea International Film Festival has celebrated Saudi filmmaking talent with the “Saudi Cinema Nights” event at Muvi theaters in Mall of Arabia, Jeddah, where they screened several short films made in the Kingdom. The screenings were a celebration of creative minds, breaking barriers and showcasing the progress made by Saudi talents on the big screens.

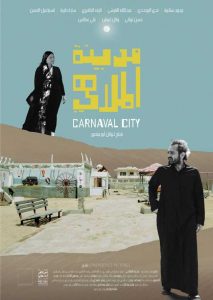

The cinematic event screened “Carnival City” along with four short films: “… And when do I sleep?” (2020), “Ongoing Lullaby” (2020), “The girls who burned the night” (2020), and “Goin’ South” (2019).

“Carnival City,” tells the story of a couple, Massoud and Salma, and their whirlwind of a journey when their car breaks down on a road trip. Searching for a mechanic in a shady small town, Massoud’s wife waits for him in the desert and the couple’s separation makes the characters go on their “own rides” in life until they meet again.

Wael Abu Mansour, the director, told Arab News that he intended to ensure that viewers interpret the story subjectively as the movie tells a random story.

“We didn’t want to force ideas on the audience or make them think in a certain way, we wanted them to interpret it in their way; we wanted to question things or try to raise questions — it is open for interpretation from different audiences,” he said, adding that the finale’s twist will have viewers questioning their initial thoughts of the main characters.

Plot twists are welcoming and fresh, “this is a smart take because the whole idea of the movie is to have a story that doesn’t have meaning to it, it is a random story. The mechanic was evil, but he wasn’t that evil. He told him he would return Massoud’s car in a day, but then returned it in about three days,” Abu Mansour told Arab News.

“It wasn’t a big deal in his point of view, but in Massoud’s point of view, he’s trying to break away from his past or life, so every minute counts for him. He doesn’t want anybody to jeopardize his journey, dream or decision. That scene, in the end, was intended because it’s a random story. If he decides to stay with Salma in the desert, it’s going to take the same amount of time to get his car back.”

Nada Al-Mojadedi, who played Salma, said she related to the character personally.

“I think it’s very relatable to a big percentage of women because a lot of women are used to being the underdog or the follower in the relationship,” she told Arab News.

“They don’t have a say on how the journey goes, although they have the spirit to handle so much and create a world within whatever circumstance they end up in. This is what women have been doing for centuries,” she added.

Al-Mojadedi explained that the separation between the two characters was a good thing.

“It’s the essence of the film to part ways. We see them at the beginning of the relationship in the car together and then they part ways and you see how each person deals with their reality, however harsh or uncomfortable it is or how much it could shake them.

“But then you see how each character embraced their journey and then you see them back again together.”

Mohammed Salama, who played Massoud, explained the character’s development through the negative events, with him starting off as arrogant before the harshness of the story breaks down his stubborn character.

Salama told Arab News that the separation between the characters was neither good nor bad. “It is a random event and it shows you that some things in life don’t have meaning and are just random.”

The event also boasted the screening of “The girl who burned the night,” where director Sarah Mesfer chose to cast her main characters as 13 and 14, “because of the strong characteristics of early teens.”

She said the movie is not derived from a personal experience, but she felt the emotions in parts of her life.

Through the imagined scenario, “the most felt feelings in the film are anger, boredom, madness, questions, rebellion. I felt all these feelings,” she told Arab News.

“The narrative of the story needed the girls to be this age, I love this age because most of the girls and boys then always believe they’re right. They think ‘what I say is right, either you have a valid answer to my question or I’m right’ and they’re always very angry and confident. This age is where you think you can change the world,” she added.

Another addition to the list was director Hisham Fadel’s “Ongoing Lullaby.” The director chose the script to be a monologue because the character is being spoken to by her inner critic, a phenomenon that everyone experiences, with scenarios playing out alongside the critic’s comments.

“The whole thing about an inner monologue is something everyone goes through and this is what some of the audience relates to. It’s something I experience — not as clear as the film with the words — but the inner monologue, the inner critic inside of us is something I experience personally. I wanted to talk about that in a film and express and communicate it to the audience,” Fadel said.

In the film, one of the characters badly injures herself, breaking the connection of the inner critic, “for that moment, the inner critic wanted to survive, it didn’t want to die. Even though things can be really bad and depressing, we have an instinct to survive, that we want to live, and that life is always better than nothing,” he said.

“Life is a gift and that’s what the inner critic faced, survival instincts kicked in, choosing life over death.”