- ARAB NEWS

- 14 Jul 2025

Carla Chahrour

DUBAI: Born in Paris to Syrian parents, multimedia artist Bady Dalloul has dedicated his practice to diverging historical, political, and sociological concepts to reflect on issues of global migration.

Through drawing, video, and objects, Dalloul engages in a revolutionary rhetoric that transcends national and cultural borders and creates a dialogue between the imagined and the real by questioning the logic of writing history and the artificial construction of territorial demarcations.

When he was a teenager visiting his hometown in Damascus, Syria, over the summer, Dalloul and his younger brother, Jad, took refuge in drawing. These early scribblings pointed Dalloul to other forms of artistic creation, which in turn led to a multimedia art practice and, in 2015, to graduating from the Ecole Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Paris in 2015, followed by receiving the Prize for Arab Contemporary Creation awarded by the Friends of the Institut du Monde Arabe in 2017.

Multimedia artist Bady Dalloul. (Supplied)

Multimedia artist Bady Dalloul. (Supplied)“My whole practice, I would say, really started as a game with my little brother that we played in Damascus during the long summers we spent there visiting family. In this game, we imagined that we were kings of fictional countries. He had Jadland and I had Badland. We started drawings inside agendas belonging to my grandfather. The more we went on writing, drawing and making collages and cutting newspapers and putting it in our diaries, the more these countries of ours were becoming real to us,” Dalloul said in an interview.

“I didn’t know what to do with this obsession of drawing and creating a parallel history for years, but I continued to do it, even when my little brother was no longer interested in this game at all,” said Dalloul.

The memories of those summers in Damascus, and the succor he found in those early drawings, still inform his work, which has been hung in galleries around the world such as at the Arab Museum of Modern Art Mathaf Qatar, Untilthen Gallery, Paris, Alexandra de Viveiros Gallery, Paris, and l’ENSBA de Paris, Paris. Dalloul has also participated in group exhibitions at Palais de Tokyo, Paris, Centre Pompidou, Paris, Gulbenkian Foundation, Valencia d’Art Modern – IVAM, Valencia, and Warehouse 421, Abu Dhabi, amongst others.

“I understood that my practice of art was a way to understand history. To understand how the countries in the near East were born in a contemporary way in the 20th century. So, Art helped me to understand first, and sometimes to even cope with history, when it was more painful,” said Dalloul.

At East-East: UAE meets Japan Vol.5, Atami Blues, starting Nov. 3 – 27 the fifth edition of an exhibition series started by curator Sophie Mayuko Arni that aims to foster artistic dialogues between the UAE and Japan through artistic collaboration and exchange, in celebration of the 50th anniversary of diplomatic relations between the two countries. The exhibition will center around the idea that “that oceans and seas are inhabited by spirits, and that artists are in a special position to honor and bring to life the hidden qualities carried by their waves” – Dalloul will be showing examples of his most recent series of work, “Inner child.”

A central idea of the installation is signified in its title “inner child” as it aims to broadly approach the issue of migration by allowing viewers to momentarily conjure experiences of unknown places and people that live outside the domains of galleries or museums.

The inspiration behind the installation stems from Dalloul’s personal experience of visiting Japan. During his first visit to Japan for an exhibition, Dalloul found that in this foreign land, he was able to feel like a child again, which allowed him to confront the uncomforting questions of identity and to consciously piece together aspects of his childhood.

Dalloul’s interest in Japan has influenced earlier works, particularly his short film “Ahmad the Japanese” named after the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish’s poem “Ahmed Al-Zaatar.” The film “Ahmad the Japanese” documents the journey of an archetypal character called Ahmad, who goes from the Arab world to Japan and “carries the stories of several people and their migration,” embodying the complicated histories of immigration and cultural mixing.

“I found that Japan was actually, for me, a place where I could take a step back and see more clearly what was going on in the countries of my parents in the near East. But also understand my life since childhood. As someone born in Paris of foreign heritage, how do you navigate with this?” Dalloul said.

“For instance, when I was visiting a bakery, it was like bakeries I have seen before, but in a very different way. In simple details. And the same was happening in a library. The same was happening when I was, and am, still not able to read and write and roaming into places and trying to understand it without the language.”

“With time, I understood that what interests me most in Japan is not only the culture which I love and respect and try to learn from, but I think most of all is this moment, this special moment when before learning the language we are in a way, understanding things or taking notice of things, but without fully understanding it,” Dalloul said.

Inspired and influenced by his new understanding of the events that have taken place throughout his maturation and self-orientation, Dalloul maximizes this experience of universal understanding by correlating it to an infant’s encounters with the world.

“When we are babies before we understand languages, our relatives tell us things and I think the baby understands, but he doesn’t understand completely because of his age, of course, but also because he hasn’t mastered the language as well,” Dalloul said.

The closest association to conceptualizing this experience of being in a foreign land, in Dalloul’s perspective, is to associate it with an infant that is unable to comprehend language yet is still capable of understanding and communicating to a certain degree, as a result of universal understanding and instinct.

The piece begins with the viewer being individually escorted into a room and to a designated seat with headphones that play a voice in a foreign language alternating between Japanese, French, English, and Arabic, which eventually interweave in a way that compels the audience to imagine an alternate reality. Simultaneously, as the voice is being played, the audience will be viewing texts, videos, and a drawing that will be aired in front of them.

For this, Dalloul collaborated with hypnotherapist Mami Nakanishi to create a protocol that would place the audience in a form of “soft hypnosis” that would put them closer to the state of mind that is experienced during infancy and aid each member to reach their “inner child.”

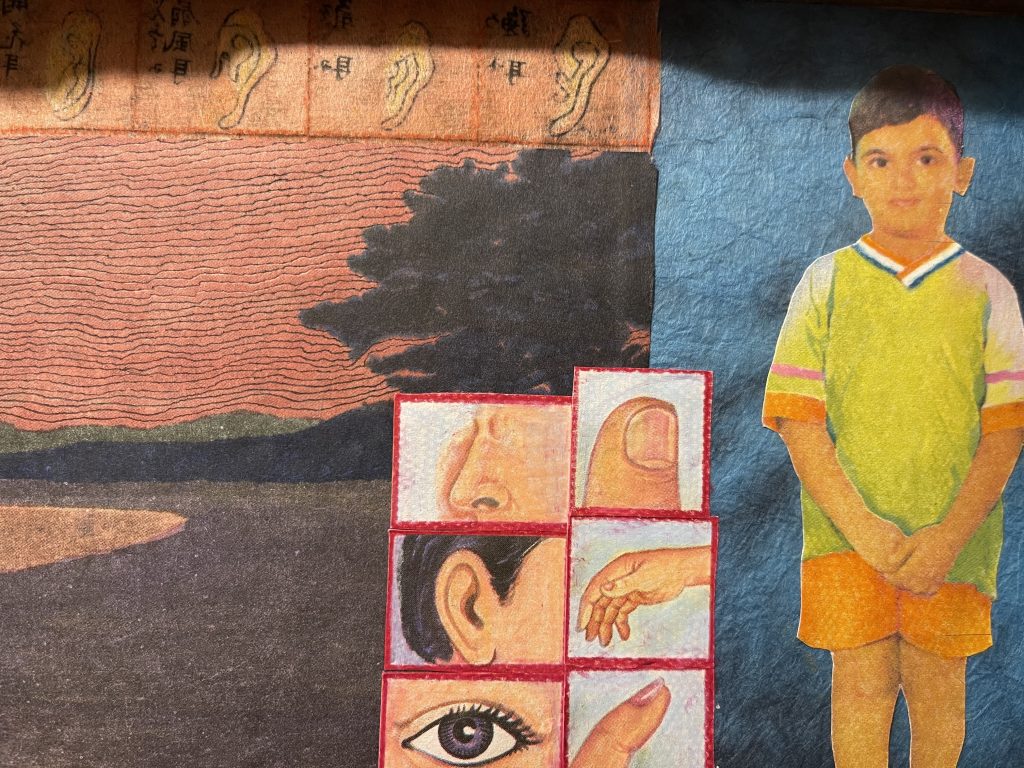

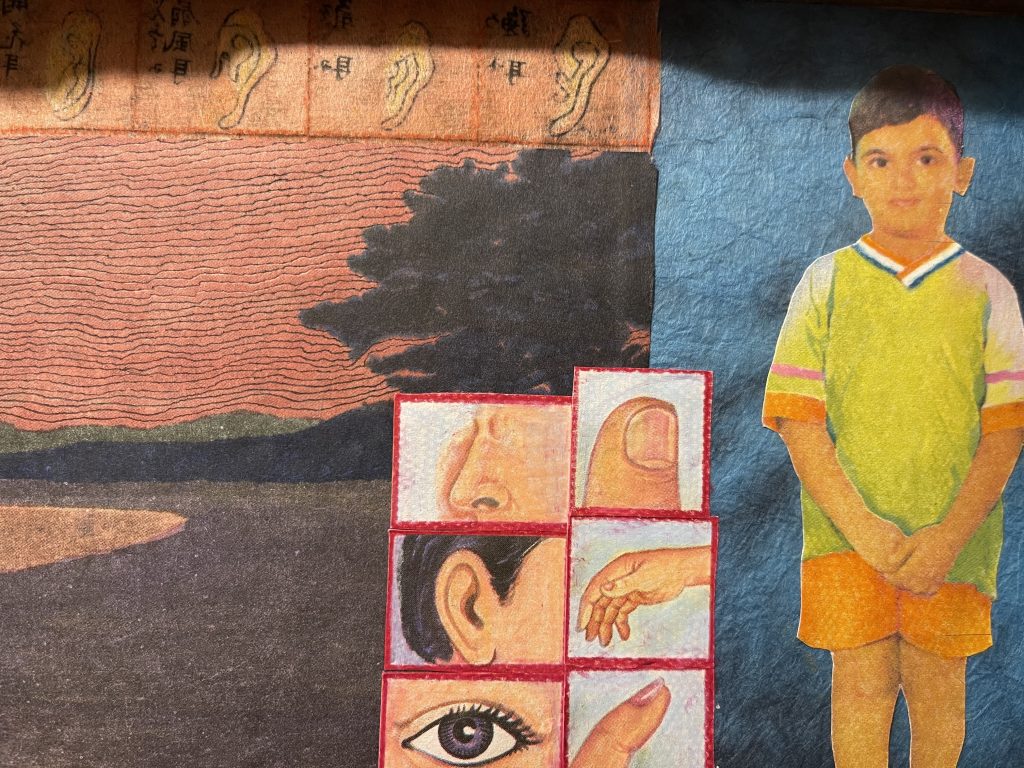

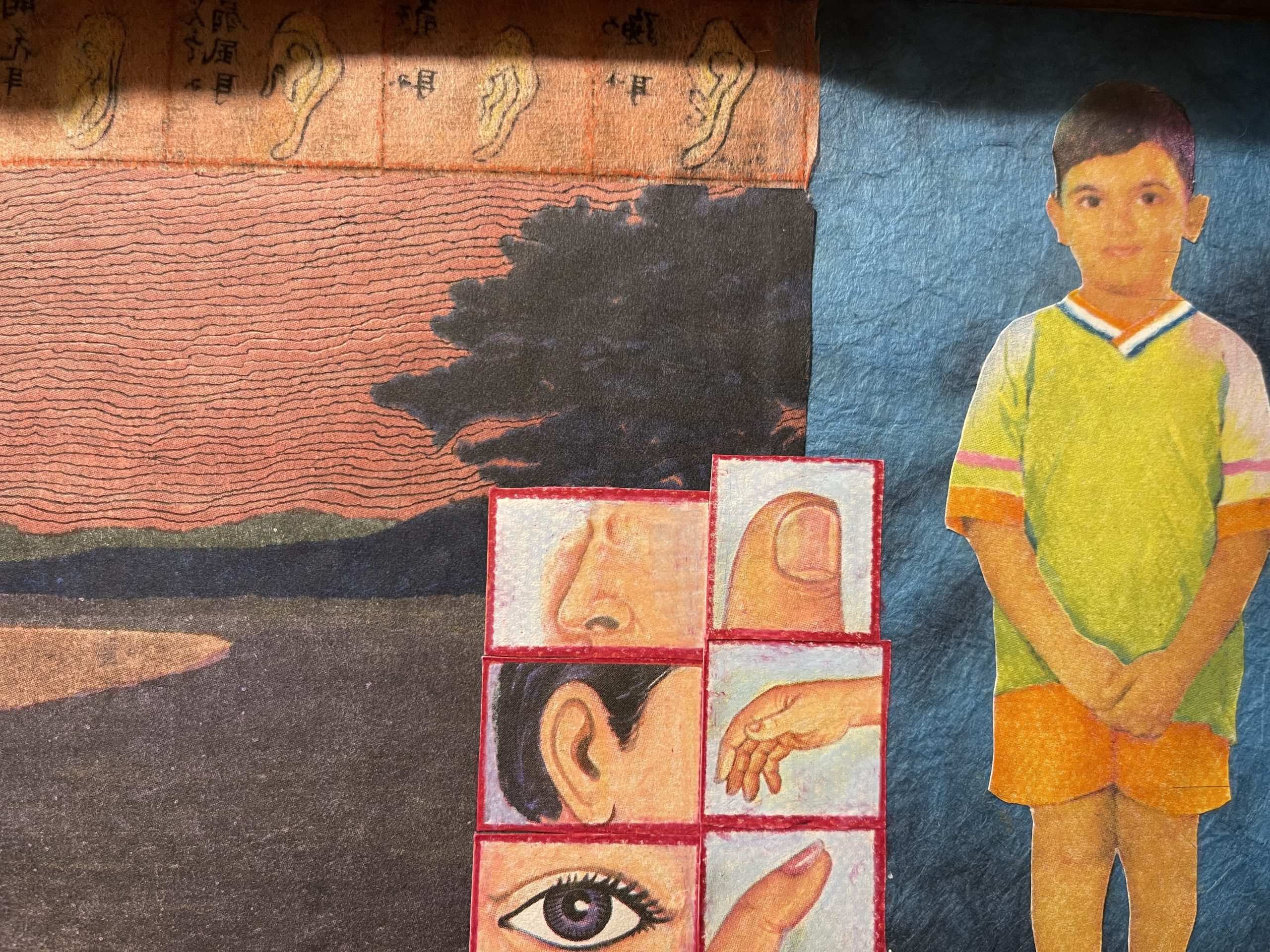

A drawing from Bady Dalloul’s installation “inner child.” (Supplied)

A drawing from Bady Dalloul’s installation “inner child.” (Supplied)After listening to the recordings, curious audience members will notice a small light in a specific area of the room, which contains a drawing of a young boy standing adjacent to a shoreline that is outlined with ears and overlapped with images of a hand, a finger, a nose, an eye, and an ear, reinforcing the childhood motif. Next to the drawing, a large ear mold that is the size of a human hand can be seen with an earphone inviting audience members to listen. The earphones contain low-frequency recordings similar to the seashell resonance that is heard when a seashell is placed upon the ear.

The installation also purposely takes place in a room facing the sea, which makes the overall experience and the message being purported throughout the installation regarding universality, the sea, and migration, particularly powerful.

Dalloul gradually introduces the theme of migration through juxtaposing the universal understanding associated with communication with cultural differences by integrating the subject coastal areas, particularly that of the sea through videos, and the sound of the sea. While the theme of the sea is universal and is something that even the youngest child visiting the exhibition could understand, this shared perception of water made Dalloul realize that everyone is part of a collective species sharing one global platform, however, some margins are consistently being contested, which makes people, particularly those from different cultures, have different affiliations to the sea.

“When people are leaving Lebanon and Syria in the near East for a better future elsewhere, they sometimes take the sea and go elsewhere. In Japan, whenever I discussed this topic about people coming from elsewhere, not necessarily from the near East, but people just coming from elsewhere by the sea, it was not a very common image, a common cachet that was right away coming to it, that was associated with the sea compared to Europe or other places. So this idea attracted me a lot. How could I also talk about people traveling from places to other places, but without going straight to the point where people perhaps would be less intent to listen?” Dalloul said.

The difference in cultures being addressed by Dalloul refers to the catastrophic stories heard in the Middle East and Africa of refugees and migrants who travel by boat to escape wars, poverty, and political oppression in their homelands. For example, according to the UN refugee agency United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), 137,000 people crossed the Mediterranean Sea in the first six months of 2015. This offers a statistical representation of the staggering number of refugees and migrants in the East that use the sea as an escape route.

In introducing this concept, Dalloul highlights the dissonance between the local understanding of the sea with that of different cultures.

The motivations for the installation “inner child” embrace emotions and experiences that are not easy to pinpoint, specifically in a country with a predominantly homogenous population. However, Dalloul’s play on sentimentality, using childhood imagery, hypnosis scripts in audio recordings, and universal concepts, allow for the collision of worlds that otherwise would probably rarely intersect, thereby creating a link between the imaginary, provided through different art forms, and the real, provided through his emphasis on real-world issues. In doing so, he manages to develop an installation that both reflects and inspires transformative understandings of people’s encounters with the world, deepening and widening the ways that sense can be made out of subjective experiences or places.