- ARAB NEWS

- 09 Jul 2025

Japan is facing a familiar challenge: How to accelerate growth in a country with significant structural and demographic issues, all of which militate against breakneck economic activity.

In the boom years of the 1980s, the Japanese for a while were buying up the world on the back of a surging economy that made them the richest people on the planet. Since then, however, Tokyo policymakers have had to grapple with the inevitable hangover from that decade- long party.

The economic experts have even coined their own term, “Japanification,” to describe the four decades of low growth, inflation and interest rates that have characterized the country’s economy, and which have been stubbornly difficult to shift. Some fear other advanced economies are now facing a similar long-term challenge.

Japan has not been in recession in that period — except in so far as the global economy has also experienced downturns toward the end of the 1990s and in the global financial crisis of 2009 — but it has been regarded as 40 years of missed opportunity for the country and its great manufacturing, technology and knowledge infrastructure.

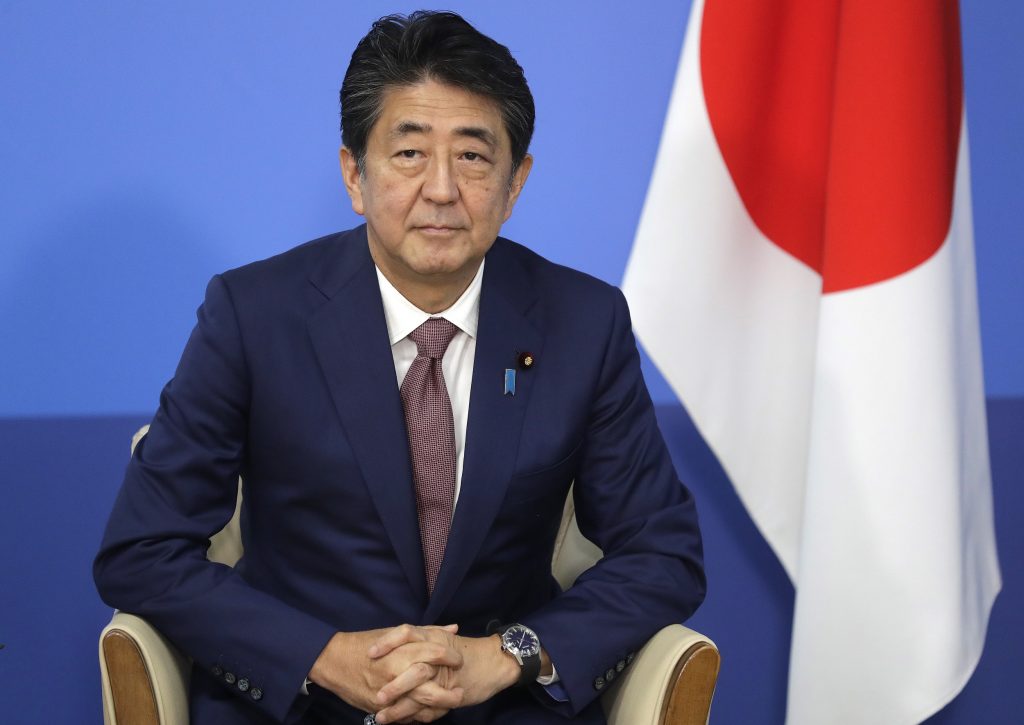

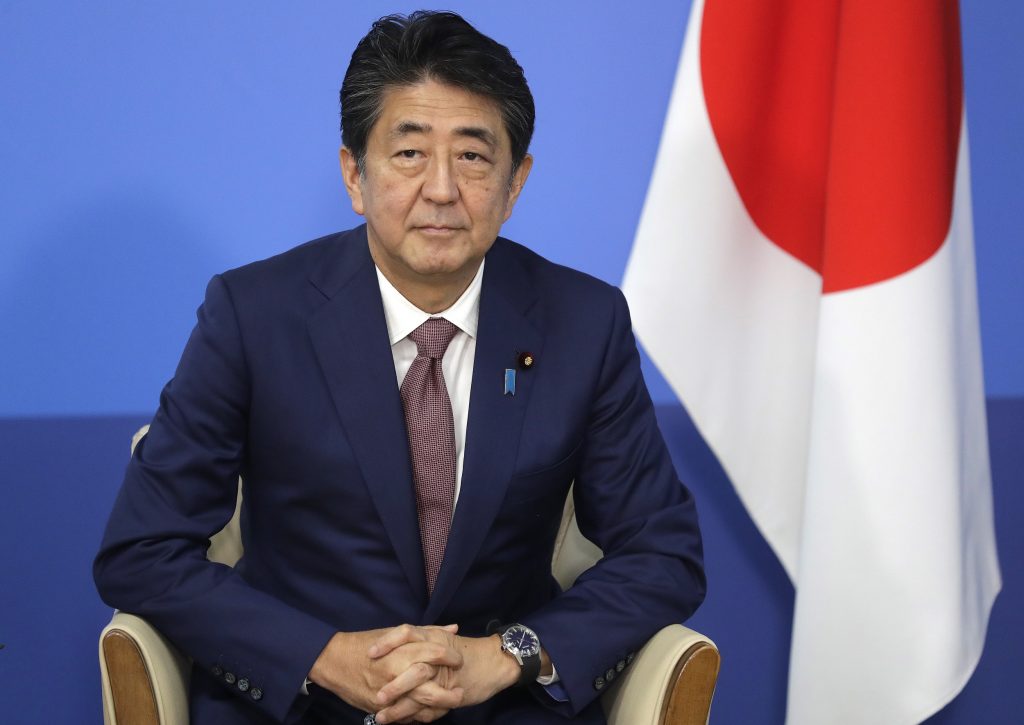

Even “Abenomics” — the policies enacted by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe since his second term in the highest office in 2012 to kick-start the economy via monetary easing, fiscal stimulus and structural reform — has had only a limited effect.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) believes that the Abe era has yielded some benefits, and that it was and is a necessary economic measure. There have been six years of stronger growth, lower fiscal deficits and unemployment, and some reforms in the labor market and corporate governance.

“But inflation remains stubbornly low, and macroeconomic and financial sector challenges are set to grow as demographic headwinds — the aging and shrinking of Japan’s population — intensify,” the IMF said recently. Forecasts for GDP growth remain firmly around the 1 percent level or below.

In 2019, those challenges have been intensified as Tokyo has had to come to grips with the depressing effects of the trade wars between China and the US that have affected the global economy and international commerce, but which are all the more challenging for an export-driven economy such as Japan.

The recent release of key economic data that showed falling statistics across a range of indicators in manufacturing, employment and consumer confidence led the government to pronounce a “worsening” outlook for its economy to dent the tentative Abe recovery, the second time that label has been applied this year.

The consumer sector has been affected by a decision to increase sales tax from 8 to 10 percent earlier this year, aimed at correcting fiscal imbalances, but also hitting demand for Japan’s increasingly important retail and service industries.

Exports have fallen for the past nine consecutive months, mainly due to the global economic and trading contraction caused by the US-China trade confrontation, but also exacerbated by Japan’s own, increasingly bitter trade dispute with South Korea over compensation for victims of World War II.

Exports of automobiles, machinery and electronic manufactured goods — staples of the Japanese economy — were among the categories of goods that have declined in the past year. Looming high over this generally depressing economic picture is the inescapable demographics of Japan’s aging population.

A huge 25 percent of the country’s population is 65 years or older, and the economic cost of an aging population — in terms of lower productivity, higher health-care costs and lower spending power — are permanent features of the economic scene. As the population shrinks further, the proportion of less-productive elderly will only increase, as will the burden on the younger, more productive sections of the population.

Post-war trends of low fertility rates and high life expectancy have sparked a challenge for policymakers that seems intractable and is certain to be a drag on economic growth, whatever the government may do to try to bring greater numbers of older people into the workforce.