- ARAB NEWS

- 06 Jul 2025

Caline Malek

DUBAI: Genetic analysis has become immensely popular in recent years, with a proliferation of commercial home testing kits allowing families to trace their ancestry back over generations and to map out their genetic origins with remarkable accuracy.

However, to pinpoint an individual’s genetic roots, these services require a huge DNA dataset. And while ancestry testing continues to grow in the West, contributing to an ever more accurate genetic portrait, it is yet to catch on in a big way in the East.

The genetic origins of modern day Middle Easterners have always been something of a mystery. Until now, more was probably known about the region’s migratory routes and ethnic mixing down the ages from cuneiform tablets than from the double helix.

Yet, beyond satisfying the public’s anthropological appetites, genetic analysis has important medical applications, chief among them the treatment and prevention of inherited genetic diseases.

Three years ago, for the first time ever, scientists from Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the UK teamed up to map the Middle East’s genetic heritage and health stretching back 125,000 years.

The researchers uncovered millions of novel genetic variants that are common to the region but considered rare elsewhere in the world. The knowledge gained in the process enabled the analysis of local genomic structures in immense detail for the first time.

The project’s findings, which were published in the scientific journal Cell on August 4, represent the first comprehensive open-access dataset in the Middle East mapping the whole human genome.

“The Middle East was always underrepresented in these studies,” said Saeed Al-Turki, a Saudi consultant in clinical genomics at Anwa Labs in Riyadh, who took part in “The Genomic History of the Middle East” study.

“We started to feel that huge discoveries were being made that could actually have a population-specific impact, and the Middle East was always missing, so this was the major drive for the study.”

Launched in partnership with the UK’s University of Birmingham and the Wellcome Sanger Institute, a British non-profit genomics and genetics research institute based near Cambridge, the study marked a crucial first step in filling the blanks in the region’s genetic history.

“The Middle East is a very important region that has a unique history compared to other local populations,” Dr Mohamed Almarri, the study’s lead author and a Wellcome Sanger Institute alumnus based in the UAE, told Arab News.

“The underrepresentation limits our understanding of the genomics and the implications of disease on these populations, so we wanted to fill those gaps that we see in the literature.”

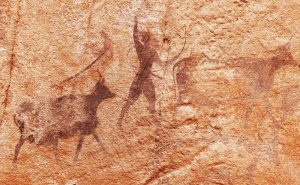

Researchers analyzed DNA from hundreds of people across the region to reconstruct their genetic heritage. What they found was that many people in the modern-day Arabian Peninsula draw their genetic ancestry from ancient hunter-gatherers and from regional Bronze Age civilizations.

Going back even further, this ethnic lineage draws its origins from an enigmatic population that left Africa around 60,000 years ago and which differs in significant ways from all other Eurasian genomes.

The findings hold intrinsic historical and medical value, allowing experts to understand the effects of migration on the Arabian Peninsula, and what genetic traits its peoples hold in common.

“For the medical impact, the more data we have from populations, the more we understand why some populations are more at risk to common diseases, such as hypertension, diabetes and others,” Al-Turki told Arab News.

One of the most significant findings of the study was the discovery of a quarter of a million single nucleotide polymorphisms, or SNPs, that were highly specific to the people of the Middle East.

“So all those previous studies that involved someone from the Middle East could have a bit of an incomplete picture,” Al-Turki said. “By adding another quarter of a million SNPs from just 130 individuals — imagine if we had 1,000 or 2,000.

“We are actually enriching the biomarkers, and that’s what leads to the discovery of what gives some populations a higher risk of contracting a certain disease.”

The study uncovered genetic variations associated with type 2 diabetes, challenging earlier assumptions that high rates of the condition in the Middle East were caused solely by the shift towards sedentary lifestyles.

Another mutation related to body mass index and the proclivity of hypertension was also found in 60 percent of Saudis and Yemenis — a figure that has long been missing from global health datasets.

“Without this project, we would not be able to understand why some of these populations are more prone to having one of the highest rates of type 2 diabetes in the world,” Al-Turki said.

“Yes, it’s related to the environment, fitness and a sedentary lifestyle, but there is also evidence of very strong genetic components that come with it, which means we should work out and be more health conscious than other populations.

“We inherited some genetic components. It’s not all bad nor good, but it’s good to be conscious about what extra steps are needed once we understand what we have.”

Based on a mapping of genomic movement, the study concluded that Bronze Age peoples from the Levant or Mesopotamia likely spread Semitic languages to Arabia and East Africa.

Moreover, they discovered that populations all over the Middle East grew at a similar rate until around 15,000 to 20,000 years ago, when the Arabian population growth stalled while Levantine populations continued to grow.

This trend was attributed to the emergence of agriculture in the Fertile Crescent, leading to settled societies supporting much larger populations.

The study also noted that aridification linked to climate change events coincided with a reduction in Arabian populations 6,000 years ago and a fall in Levantine populations 4,200 years ago.

A distinct mutation which allowed people to digest lactose was found in genomes local to modern-day Saudi Arabia, Yemen and the UAE, with a probable attribution to the domestication of animals providing a source of dairy.

Although they have merely scratched the surface of the Middle East’s genetic heritage, the findings of the project are critical to understanding the present-day gene pool and what regional nations can do to plan for future health needs.

Almarri, the study’s lead author, hopes to delve even deeper into the region’s genetic past.

“Our region remains to be understood,” he told Arab News. “Every person in the future will have a tailored treatment for any disease that they have, and we need researchers from the region to investigate this in our populations.”

More regional collaboration will be needed, drawing together hospitals and universities, to identify the link between genetic mutations and specific diseases and to usher the Middle East toward an age of genetics-informed medicine.

“There is so much work done in separate organizations in the Gulf and in the Middle East,” Al-Turki said. “They’re usually not published in high-ranking journals like Cell because they are a single population.

“This is an example of how much higher we can go in the quality of research once we collaborate with different countries. We cannot do it alone.

“It is only when we collaborate with others that we can actually be a part of the bigger picture.”

——————-

Twitter: @CalineMalek