- ARAB NEWS

- 15 Jul 2025

TOKYO: Takeout menus. Directions for attending a funeral. A leaflet from a local shrine, announcing the cancellation of summer festivals.

These humble, everyday artifacts of life in the pandemic have found a home in the Historical Museum of Urahoro, in Hokkaido, northern Japan, a town of just 4,500 residents that lacks a McDonald’s or movie theater.

But thanks to the museum’s curator, Makoto Mochida, it has a repository of the dross of the moment, stuff that may tell future generations what it was like to live in the time of COVID-19 — how life was profoundly changed with social distancing and growing fears over the outbreak.

“I am fascinated by how things connect with people,” Mochida said.

Some people are surprised he’s hoarding what appears to be garbage, said Mochida, who has problems throwing away things at home, too.

“Things furnish an excellent way to accurately archive history,” he said.

So there are documents that show how children were taught to shift to online schooling. And instructions, complete with diagrams, on how to make a mask from a handkerchief.

Several hundred objects have been collected so far, after a call went out to residents.

In the wake of the last great pandemic — the so-called Spanish flu of 1918-19, which killed more than 50 million people globally — letters and diaries provided insight into daily life.

But these days, those analog communications have all but vanished. And their digital versions, like emails and social media posts, are all but lost in a sea of cyberspace, Mochida said.

So it is left to Mochida to curate the flotsam and jetsam of the coronavirus.

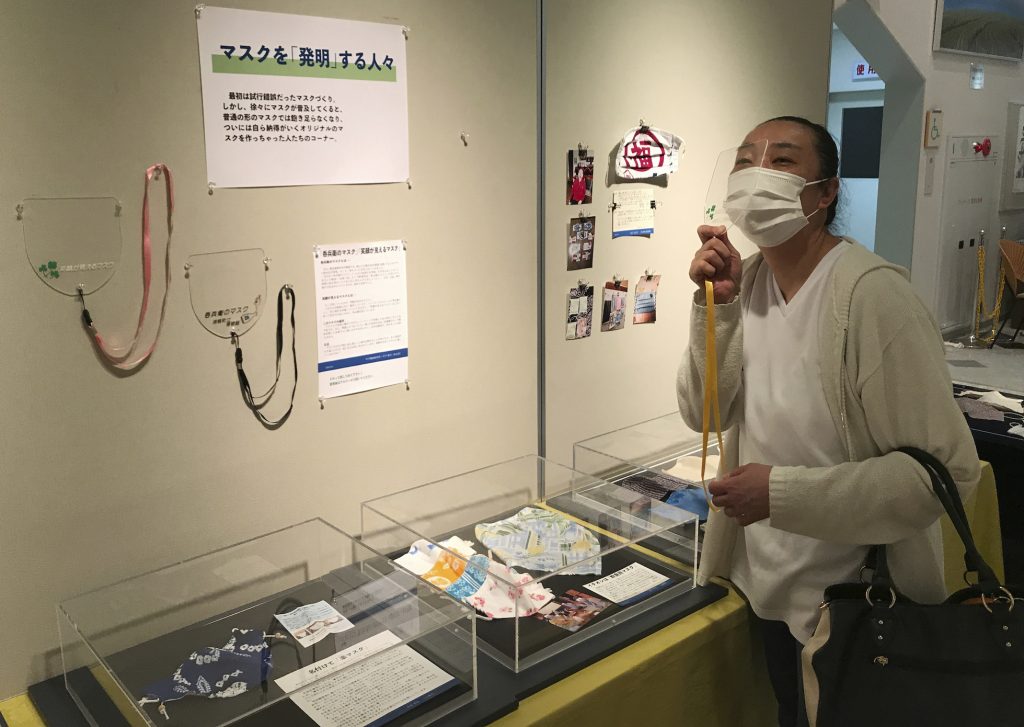

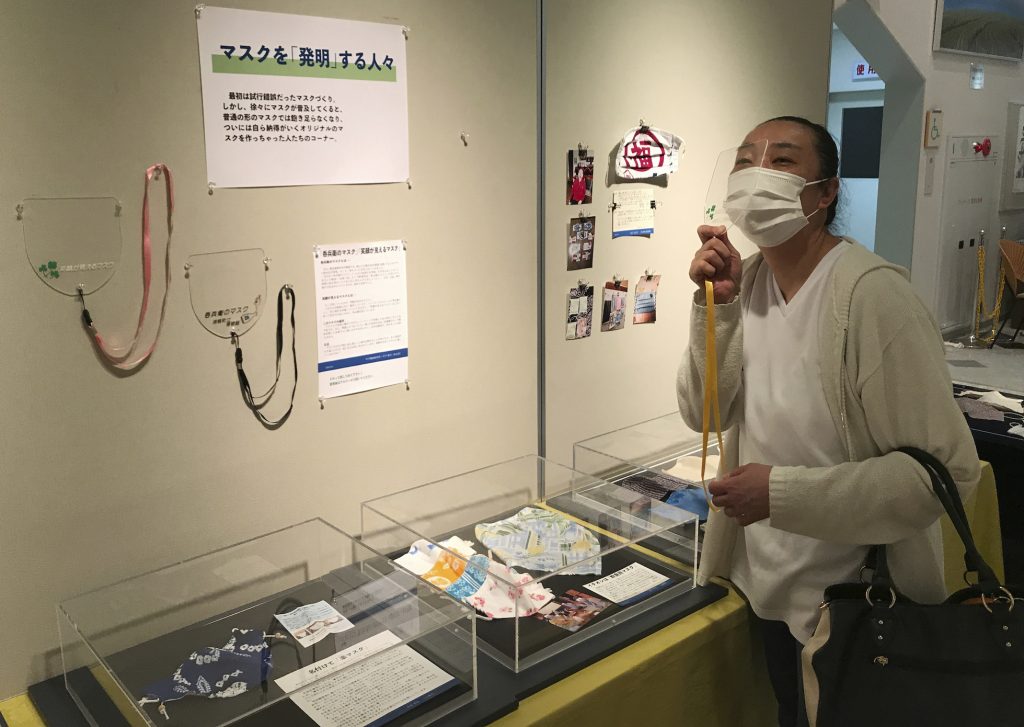

He is planning a big exhibition of his finds next February to follow up on the smaller display now at the museum, located in the Urahoro library, showing how masks have evolved in a short time.

At first, masks were hard to find in Japanese stores. Handmade varieties were primitive, concocted from old shirts and stockings.

Then came innovations, like draping masks that allow for eating and drinking, or sheer plastic ones. They eventually became fashion statements, some with fancy embroidery.

Cases of COVID-19 have been growing in Japan, but they have not reached the levels of the hardest hit nations like the U.S., Brazil and parts of Europe.

Urahoro has not yet recorded a single case. At first, the community brushed the outbreak off. Then fears began to creep in, especially toward outsiders, and households with adult children working in Tokyo or nearby cities, who could come home to visit.

Then came the adjustments. For the tiny town, takeout — including the local specialty “spa-cut,” or meat-sauce spaghetti topped with a fried meat cutlet, usually pork — has become the rule after restaurants shut to in-person dining. Before the pandemic, it wasn’t even an option.

Shoko Maede, who was born in Urahoro and works as a cook at a nursery school, feels she can almost picture people decades from now trying to remember life amid the pandemic.

“They may think, ‘Oh, so this was the way it was,’” she said, after visiting the museum.

“Things do reveal how people think.”

AP