Carla Chahrour

DUBAI: Half a century after astronauts last walked on the Moon, a new age of space exploration is dawning with Japan among several nations, including Saudi Arabia, who are focused on gathering data about life beyond planet Earth.

Japan’s Asteroid Explorer Hayabusa was the first to bring asteroid dust back to Earth after touching down on Itokawa in 2005. On Feb. 22, 2019 the Japanese spacecraft Hayabusa2, the successor to the first mission, completed a touchdown on the surface of the asteroid Ryugu where it retrieved samples.

The UAE launched its Hope Probe in 2020 and became the fifth space agency to reach the Red Planet in what was the first Arab interplanetary probe.

Saudi Arabia may also soon be represented by the Saudi Space Commission, or SSC, that was launched in 2018 by royal decree, which intends to accelerate economic diversification, enhance research and development, and raise private sector participation in the global space industry.

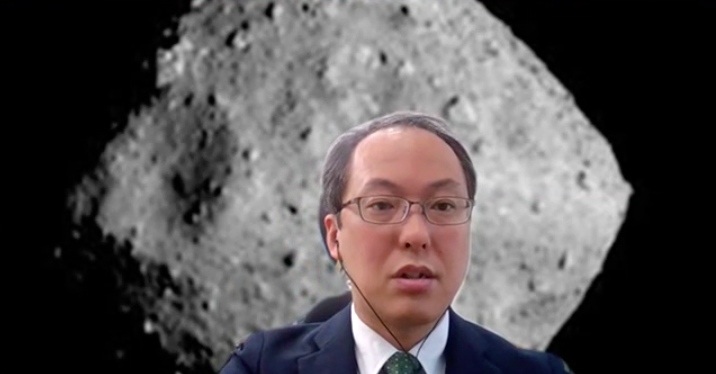

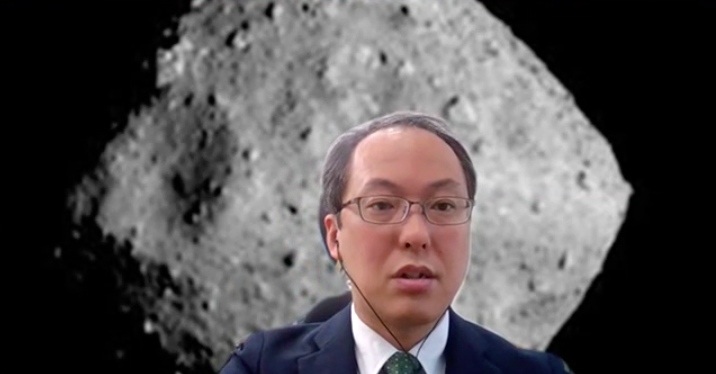

In an exclusive interview, Arab News Japan spoke to the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency’s Yuichi Tsuda about his country’s plans for the future. Tsuda is the project manager of the Hayabusa2, and also the youngest person to be appointed in such a crucial position at JAXA. He outlined the processes involved in the exploration of Ryugu, how it helps scientists understand the manner in which Earth was formed in the early solar system, and the challenges involved in the execution of the project.

Tsuda was first appointed as an assistant professor at the Institute of Space and Astronautical Science, or ISAS, in 2003, where he was assigned to the first Hayabusa project. He worked as the spacecraft’s systems and operations engineer, and devoted extensive effort into realizing the world’s first solar sail spacecraft, often called a space yacht.

During his tenure, Tsuda invented the forging method for the thin and flexible large solar cell, and the deployment mechanism, after which he became the deputy lead of the solar sail mission. In 2007, during the conception of the Hayabusa2 mission, Tsuda was assigned as the role of the lead engineer.

After the launch, he was appointed the project manager. He modestly said that it was just by “chance” that he was able to land the coveted position, even though he had been extensively involved in developing the spacecraft.

Hayabusa2 was launched in 2014 aboard the H-IIA Launch Vehicle No. 26 from Tanegashima Space Center in Japan to collect samples from Ryugu, an asteroid that orbits the sun between Earth and Mars and has a diameter of just over 900 meters.

Tsuda explained that small body exploration for samples, from asteroids and comets, has been one of the main pillars of ISAS’ activities. “Japan has a long history of space science and interplanetary missions but we have just come to say that space exploration is our strong point in 2010, after almost 20 years of exploration in this field. This is the result of how we try to optimize our portfolio to maximize our outcomes amidst resource constraints,” he said.

“ISAS, with its limited budget, has focused its attention on small body exploration. The small bodies, which until 20 years ago had not attracted much academic attention, are now an area of particular interest due to their low gravity and the fact that they exist close to earth. The launch of Hayabusa was the first interplanetary round-trip mission and it stimulated the planetary science of asteroids and comets which (is) currently a very hot field,” Tsuda added.

Describing the story of the Hayabusa2 as a “typical example that explains JAXA’s attitude towards space science and space exploration,” Tsuda said that the growing interest in asteroids stems from the idea that they are remnants of planet formation.

They retain information about what the ancient solar system was like 4.5 billion years ago and aid in providing clues about the origins of life. This information can never be fully known from large fully evolved bodies such as Earth and Jupiter.

The decision to explore Ryugu, which is more than 300 million kilometers from Earth, out of the 1.2 million asteroids that have been discovered within the solar system, is multifaceted.

The first reason involves the position of the asteroid within the solar system and its association with Earth. Elaborating on the reason, Tsuda said that the key word in discussing Earth-like planets is the “snowline” which refers to the virtual boundary between Mars and Jupiter.

Beyond the snowline water can exist in the form of ice, whereas inside the snowline, which is close to the sun, water evaporates. This means that planets within the snowline are dry while those beyond it are wet. However, Earth, which is positioned within the snowline and should therefore be a dry planet, contains plenty of water.

It is then believed that since this is the case, water must have been brought to earth, making it habitable. Consequently, it has been hypothesized that the small bodies born outside the snowline played the role of a water-delivery capsule, according to Tsuda.

Ryugu is currently positioned within the snowline, but it has been theorized that it previously existed beyond the snowline, which is both rare and significant. “A detailed analysis of samples returned from an asteroid beyond the snowline, being brought for analysis on the ground, is the best way to decipher the story.

“To bring a sample from asteroids is not easy business. A number of challenging and extremely sophisticated technologies are required to achieve sample returns from extraterrestrial planets. This is the mission scenario of the Hayabusa2,” Tsuda said.

The second reason behind the decision to explore Ryugu involves its close proximity to Earth, which enhances the likelihood of conducting a successful round-trip. “Ryugu is within the snowline and very close to … Earth so it’s easy to go there and easy to make a round-trip,” Tsuda said.

The third reason is that Ryugu is a C-type, or carbonaceous asteroid, meaning it is full of carbon molecules known as organics, as well as hydrated minerals. Such molecules indicate the possibility that asteroids could have seeded Earth with the organic matter that led to life.

“By obtaining the sample of Ryugu, with its rich organic compounds and hydrated minerals, namely carbon and water, we may be able to get a clue about the origin of life. We have already investigated the return samples and have already acquired clues of organic compounds and confirmed the presence of water in the sample.

“In that sense, we are already happy about the results obtained and are interested in specific chemical compounds or compositions of the Ryugu samples that would tell us how Ryugu was born and how the solar system was evolved, and also maybe we can (determine) in some way the origin of life on earth,” Tsuda said.

Despite extensive planning to mitigate the risks involved in the mission, Tsuda described the process of the first touchdown on Ryugu as a “long and winding road.” Ryugu was covered with boulders scattered across the asteroid that forced them to change their strategy for the landing operation.

After undergoing numerous accuracy performance tests, conducting meetings with international colleagues, and delaying the mission by four months, Hayabusa2 was able to successfully make two touchdowns on Ryugu, where they achieved several world firsts, one of which was completing two landings by one spacecraft. Hayabusa2 also fired a copper projectile into the asteroid’s surface and collected the scattered samples to ensure the attainment of asteroid dust that had not been exposed to the solar system’s weather, which would enable thorough analysis of its geological history.

“Exploration is about stepping into the unknown where the unexpected is expected. Science has evolved from the unexpected, so challenges are important (and) if we avoid challenges, we would remain nobod(ies),” Tsuda said.

In elaborating on the challenges encountered, Tsuda said that the mission faced several challenges. He also showcased aunique point of view that aided in the achievement of their successes in space exploration that entails the utilization of resources available and transforming their weaknesses into strengths.

“A small budget doesn’t always mean that we can have less outcome. A small budget can mean we can take more risks, or risks that are adequate with our budget level.

“So we considered the risks of not trying the second touchdown as well as trying it. Sample capsule recovery was another challenge when the world was in the fog of the pandemic, and the success of the recovery owed itself to the focused determination of our team and our organization,” Tsuda said.

Japan eventually retrieved a capsule of asteroid dust, obtained from Ryugu, from Australia’s remote Outback, successfully completing the six-year mission. JAXA distributed 15 percent of the capsule’s contents to scientists around the world and stored 60 percent for future generations.

The sharing of the samples represents a collaborative approach undertaken by the agency and showcases a new perspective toward space science, which makes the “space race” seem like a concept from the past. “Today space is more about collaboration rather than a ‘space race’ so the increase in the number of people and countries that can cooperate with each other is a good thing,” Tsuda said.

He welcomed the efforts of countries like Saudi Arabia.

“It is good for countries with national power to conduct space activities in a manner that (is commensurate) with their national power. International cooperation is such an exciting destination. I hope that Saudi Arabia will contribute to the development of the wisdom of Saudi Arabia itself and the wisdom of mankind as a whole,” Tsuda said.

JAXA will continue to be a story of space exploration, technology, and science with ambitious upcoming missions that include a lunar landing in 2022, a comet flyby mission in 2023, and a Mars moon sample return mission in 2024.

These plans showcase the agency’s determination to contribute to the field within their small, yet variable areas of focus, allowing for the advancement of human knowledge about the universe, which is an endeavor that is still far from complete.