TUNIS: With fighting in Gaza between Israel and the Palestinian militant group Hamas sending shockwaves through the region, wars elsewhere in the world — particularly in Sudan — are in danger of being overlooked altogether.

For more than six months, the conflict between the Sudanese Armed Forces, or SAF, and the paramilitary Rapid Support Forces, or RSF, has raged across Sudan, leading to mass displacement, shortages of food and medicine, and even cases of ethnic cleansing.

Saudi Arabia and the US have resumed joint efforts in Jeddah to get the feuding parties to reach a settlement after several ceasefires collapsed in recent months. However, the conflict is complicated by the porous borders and instability that characterize the wider region.

Experts say that Sudan has become a magnet for fighters from across Africa’s Sahel — a belt of territory between the Sahara Desert to the north and the savannas and tropical forests to the south, spanning 12 African nations, from Mali in the west to Sudan in the east.

The result of this influx of young men, many driven to desperation by other conflicts and lost livelihoods in their own countries, has potentially significant implications for the security dynamics of the wider African continent, the Middle East, and beyond.

“These forces are not fighting for a cause, but simply for a paycheck, which means they have no regard for civilian life or property,” Cameron Hudson, a senior associate of the Africa Program at the Washington-based Center for Strategic and International Studies, told Arab News.

The Sahel, home to about 135 million people, has a semi-arid climate and is characterized by seasonal rainfall and drought-prone conditions. Though rich in minerals, it grapples with extreme poverty, primarily because of poor leadership, corruption and geopolitical factors.

A rash of military coups in Mali, Burkina Faso and more recently Niger, combined with long-running insurgencies orchestrated by Islamist militant groups affiliated with Daesh and Al-Qaeda, have led to further destabilization.

With the regional economies in no shape to create jobs for a booming youth population, the Sahel is increasingly a source of recruits — both willing and unwilling — to cater for a multitude of conflicts, to say nothing of endemic violence, small-arms proliferation and violent extremism.

Anecdotal evidence suggests that many fighters from Chad, the Central African Republic, Libya and Sudan’s Darfur region have converged on the devastated Sudanese capital, Khartoum, to join the RSF’s ranks.

On Saturday the RSF claimed to have taken control of the army headquarters in West Darfur’s capital, El-Geneina. The group now wields significant influence in Darfur, where it seized control of Nyala, Sudan’s second largest city, on Oct. 26 and an army base in Zalingei on Oct. 30.

Around the same time, the RSF seized control of the airport of Balila oilfield in the state of West Kordofan. It also has influence in Al-Jazirah, a state south of Khartoum, and in the far southeastern state of Blue Nile.

The capture of territory, resources and spaces to train new recruits stands to strengthen the RSF. But in order to further extend its grip across the country, it will require additional manpower.

“The paramilitary is clearly trying to expand the scope of this conflict into areas not under its control and the fighting has not yet occurred,” Hudson said. “To do that, they need added forces and an influx of weapons.”

Sudan has been in the throes of internal strife since April 15 when fighting broke out between the SAF, led by the country’s de-facto military ruler, Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan, and his deputy-turned-rival Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo’s RSF.

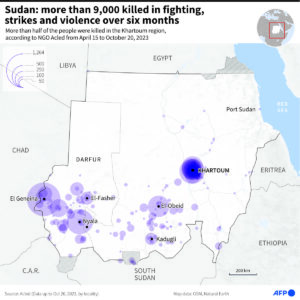

To date, the conflict has claimed more than 9,000 lives, according to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project, or ACLED, a nonprofit.

Civilians are bearing the brunt of the crisis, with many caught in the crossfire, targeted for their ethnicity, robbed, raped or dying as a result of food shortages and lack of access to medical assistance. Both sides accuse the other of abuses and of blocking humanitarian access.

According to UNHCR, the UN Refugee Agency, about 6 million people have been forcibly displaced both internally and across international borders into neighboring Egypt, Chad, South Sudan and Ethiopia since the conflict began.

The RSF is a complex coalition of state-sponsored militias, local armed groups and foreign mercenaries. Its core consists of nomadic Arabs from Sudan’s west, supplemented by Chadian Arab and non-Arab auxiliaries from the Sahel and Sahara regions.

Groups from Sudan’s far west, such as the RSF-aligned Tamazuj, or Third Front, have joined the fray. The stated aim of the Tamazui, which consists primarily of Arabs from Darfur and Kordofan, is to end their perceived marginalization.

However, this rough tribal coalition is far from united as, throughout the ages, local Arab tribes have often been at loggerheads over power and ownership of resources.

Ideologically, “the RSF lacks a clear, unifying political program,” Reem Abbas, a Sudanese author and political analyst, told Arab News.

“Motivations range from ethnic grievances to a desire for regime change, and some fighters are drawn by the charismatic leadership of Mohammed Hamdan Dagalo. Others fight out of sheer necessity, seeing no alternative livelihoods other than as soldiers for hire.”

While the flow of fighters currently travels from west to east into Sudan’s urban core, this could change if the RSF’s military efforts stall in central Sudan. In one possible scenario, fighters may return to their villages, leading to more inter-tribal conflicts and radicalization.

“Sudan will be faced with the prospect of thousands of unemployed mercenaries left in the country, preying on populations to sustain themselves,” Hudson said. “This return to warlordism could well keep Sudan’s peripheral regions mired in conflicts for years to come.”

Such a denouement seems increasingly likely as the RSF burns through its resources.

“The RSF appears to have already suffered significant losses in this protracted conflict, including the loss of arms, weapons, armored vehicles, high-ranking officers and well-trained soldiers,” Osama Ahmed Idrous Ahmed, a security studies professor at Omdurman Islamic University of Sudan, told Arab News.

“While recruiting efforts may be gaining momentum, it’s doubtful that the RSF can regain the momentum it once had. Instead, the war has transformed into a prolonged cycle of destruction for Sudan, with no clear outcome favoring the RSF.

“It is imperative to halt the RSF’s actions, prevent further damage, and put an end to the commission of new war crimes.”

The surge in the number of foreign recruits driven by monetary incentives could sow the seeds of the RSF’s own destruction. A disparate cohort lacking ideological unity and with dwindling dividends could easily break apart.

Ahmed believes foreign actors will likely exploit these divisions to advance their own interests, “contributing to factionalism and infighting within the RSF.”

According to a recent Wall Street Journal report, Turkish Bayraktar TB2 drones have been delivered by a neighboring country to the SAF, while its soldiers are undergoing training abroad to improve their handling of the unmanned aerial vehicles.

It quoted ACLED as saying that military airstrikes have inflicted significant damage on RSF facilities and weapon warehouses around Khartoum since late August.

The SAF, meanwhile, faces recruitment problems of its own. Its commander, Al-Burhan, has called on the Sudanese youth to join the army “to counter internal and external threats” in a bid to turn the tide of war.

On the international stage, he has undertaken visits to Egypt, South Sudan, Qatar, Eritrea, Turkiye and Uganda, as well as the UN General Assembly in New York in September, to rally support.

Sudan’s recent announcement of the renewal of diplomatic ties with Iran underscores Al-Burhan’s pursuit of resources and weapons amid persistent concerns about his legitimacy to rule.

But as long as the war and the attendant humanitarian crisis in Gaza rivet international attention, appeals to stem the flow of funding, weapons and fighters to Sudan’s warring factions will likely go unheard, with potentially serious consequences down the line.