- ARAB NEWS

- 13 Jul 2025

“I can’t do anything with my land because of the lack of water,” he said.

Fileli is just one of many farmers who have been left high and dry by increasingly long and intense droughts across North Africa.

“When I started farming with my father, there was always rain, or we’d dig a well and there would be water,” said the 54-year-old, who farms around 22 hectares of land near the northern city of Kairouan.

“But these last 10 years there has always been a lack of water. Every year the water table drops three to four meters.”

Fileli showed AFP his sprawling orchard of olive trees. With the olive harvest approaching, some bore small, shriveled fruits, but the rest were dead.

He said that over the past decade, around half of his 1,000 olive trees have died due to drought.

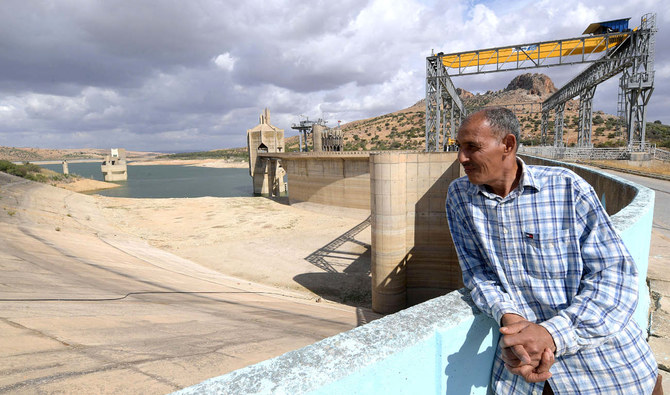

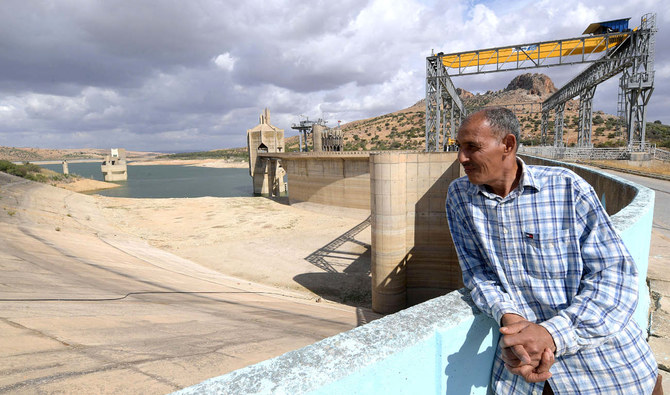

The country’s water crisis is clearly visible at the Sidi Salem reservoir, which supplies water to almost 3 million Tunisians, including the capital Tunis.

Years of drought have left its water level critically low, an ominous sign for the region’s future.

The surface of the lake lies 15 meters below a high-water mark left by floods in 2018. Engineer Cherif Guesmi says that he has seen “terrifying climate change” during a decade working at the dam.

“The situation today is really critical,” he said.

“There’s hardly been any rain since a 2018 flood, and we’re still using that water today.”

As Tunisia sweltered in record temperatures topping 48 degrees Centigrade (118 Fahrenheit) in August, the reservoir lost 200,000 cubic meters per day from evaporation alone, he said.

Despite heavy rain in late October, little fell in the dam’s catchment area and the reservoir remains at just 17 percent of capacity, according to official figures this week.

Tunisia’s neighbors face similar challenges. The North African nations of Algeria, Libya, Morocco and Tunisia are among the 30 most water-stressed countries in the world, according to the World Resources Institute.

Experts warn this could drive social change that is likely to upset the region’s tenuous sociopolitical balances.

Fileli has also had to delay plans to sow winter wheat or barley in his fields.

He lists the knock-on effects: Smaller crops mean farmers fall deeper into debt and hire fewer seasonal workers, adding to an 18 percent unemployment rate which has pushed many to leave the country.

“My son is saying, ‘Dad, should I go and find work in Tunis or somewhere else? If things stay like this I have no future here’.”

The problems facing Tunisia are felt across the region.

“The water table across North Africa is dropping due to a combination of over-pumping and lack of precipitation,” said Aaron Wolf, a professor of geography at Oregon State University.

He cited Libya’s massive Man Made River, a huge system built under the late dictator Muammar Qaddafi, to pump “fossil water” from finite aquifers in the southern desert to the country’s coastal cities.

In Algeria — the scene of huge forest fires in August — valuable drinking water is regularly used for irrigation and industry.

And in Morocco, drought has “strongly affected agricultural production,” according to the economy ministry.

Rabat’s Agriculture Minister Mohammed Sadiki has told parliament that rainfall is down 84 percent from last year.

Wolf said the implications of drought go far beyond the countryside, causing migration within and across national borders.

“It’s in all parties’ interests to solve rural water problems,” he said.

“Drought drives all the things that lead to political instability: rural people migrating to the city, where there is no support for them, exacerbating political tensions.”

Hamadi Habaieb, head of water planning at Tunisia’s environment ministry, said a combination of less rainfall and a growing population would mean that by 2050, the country would have “far less” water available per person.

“Tunisia needs to adapt,” he said.

But he insisted that “farming has a future in Tunisia, although we will need to move toward very specific crops … that can deal with a lack of water and to climate change.”

For Fileli, any solution may come too late to save his business — and the farming career of his son, aged 20.

“I’m thinking of giving up, going to the capital, somewhere else,” said Fileli.

“As long as there’s no water, no rain, why stay here? At least my children could find another future.”

AFP