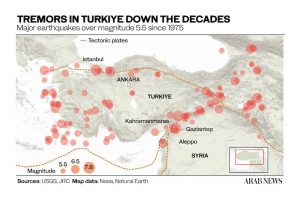

As of Monday, the death toll stood at more than 44,000, making it the worst disaster in modern Turkish history. But this number is expected to rise further given that more than 160,000 buildings collapsed or were severely damaged and many people are still unaccounted for.

The frantic search for survivors among the rubble has now been replaced by the search for answers. Many are now asking who bears responsibility for poorly enforced building codes, which cities might face a similar fate when the next quake hits, and how such a horrific human toll can be prevented in the future.

The situation in Istanbul, home to more than 16 million people, raises particular concern. Located on the North Anatolian fault, the city suffered a major earthquake in 1999, which killed more than 17,000 people and exposed corruption in the construction sector.

In the days since the Feb. 6 earthquakes, critics have accused Turkish authorities and construction firms of failing to learn from past mistakes, leaving the country ill-prepared for the disaster, despite the well-known seismic risks in the region.

When Recep Tayyip Erdogan came to power in Turkiye in 2002, one of his pledges was to make buildings safer. “Buildings kill, not earthquakes,” he tweeted in 2003.

Regulations were bolstered in 2018, with new requirements for high-quality concrete, reinforced with steel bars. However, many existing buildings with defects have not been properly retrofitted.

The government has also issued amnesties on nine occasions during its 20-year rule for buildings that did not meet these standards, even in earthquake-prone zones. This was often the case around election time.

Some 205,000 buildings in Hatay and 144,000 in Kahramanmaras in the country’s southeast — both near the epicenter of the recent quakes — were granted amnesties in 2019, just before elections were due to take place.

Pelin Pinar Giritlioglu, head of the Istanbul branch of the Chamber of City Planners, told Arab News that hundreds of thousands of buildings in the earthquake-affected region had benefited from the amnesty policy. The same is true for Istanbul.

“A potential quake in Istanbul will unfortunately have a more destructive power because the city is densely populated with a higher number of buildings, and it could transform the city into a mass graveyard because thousands of buildings are with unclear status regarding their resilience against an earthquake,” Giritlioglu said.

Poor urban design, legalization of structures by merely fining construction firms without demanding retrofitting, and execution of politically motivated development plans without enforcement of building codes can only have fatal consequences, Giritlioglu warned.

“Earthquake resistance requirements were not sought even in state buildings,” she said. “Hospitals and airports were opened along fault lines with much fanfare despite all the warnings. The region then did not get timely humanitarian assistance because the quake also hit the public infrastructure.”

Giritlioglu says that authorities should launch across the country social housing projects with buildings whose resistance to earthquakes can be regularly monitored.

“In addition to the safe buildings, we should make cities well prepared for any quake by introducing evacuation paths as well as building public hospitals in safe areas,” she said. “We need this rather than mega-projects and politically motivated master plans.”

Taner Yuzgec, president of the Chamber of Construction Engineers, told Arab News that periodically issuing blanket amnesties to violators of building codes amounts to a crime. “We repeated this warning each time. But nobody wanted to hear us at those times,” he said.

In fact, a new amnesty for recent construction works was awaiting parliamentary approval just a matter of days before the quake struck the region. According to a report by the Environment and Urbanization Ministry in 2018, more than half of all buildings in Turkiye are considered unsafe.

OZAN KOSE / AFP

“The history of flouting of building codes by Turkiye’s construction industry dates back to 60 years ago, and it was mainly triggered by an intensive emigration wave within the country and the desire of contractors to get rich in the shortest time period,” Yuzgec said.

“It then became politically linked over the years because they were closely connected with the ruling governments.”

According to Yuzgec, malpractice exists at every level, starting with the contractor who uses cheap building materials and inexperienced engineers and architects to maximize their profits.

Responsibility then continues up the chain to the certifying authority and the supervisors who sign off on these risky structures without the necessary inspections.

“Authorities claim that almost all the buildings that collapsed were older and built before the ruling government took office,” said Yuzgec.

“But we also saw new multi-story buildings that collapsed like a pack of cards because several of them benefited from a controversial amnesty and changed the original construction plans without any accountability.

MERT CAKIR / AFP

He added: “We should be able to certify the proficiency of all engineers and architects when they graduate. They should not be allowed to give licenses to the buildings without getting such a proficiency certificate.”

Yuzgec believes the enormous loss of life and infrastructure could have been avoided had the authorities listened — rather than accusing industry professionals, scientists and disaster mitigation scholars of fear-mongering.

“Properly planned cities and buildings constructed in accordance with the relevant building codes would have withstood such an earthquake. Rebuilding the old structures in areas with high seismic risks would be a repeat of the disaster,” he said.

Experts point out that Turkiye already has sufficient legislation covering construction standards, but that a combination of weak enforcement, corrupt construction practices and insufficient monitoring makes these laws ineffective.

“If the current legislation was enforced properly in the region, with a qualified monitoring process, the scale of destruction would not be so high,” Gencay Serter, president of the national Chamber of City Planners, told Arab News.

Scores of people have been arrested since the Feb. 6 earthquakes, accused of violating building regulations. However, no legal action has yet been brought against the officials who approved these buildings, sparking a public outcry.

Of the 612 suspects identified so far, 184 have been detained, 55 are in police custody, and 214 have been released on bail, according to Bekir Bozdag, Turkiye’s minister of justice. Among those arrested is Okkes Kavak, the mayor of Nurdagi, one of the hardest hit districts in Gaziantep. Reports say he was the contractor of two buildings that collapsed during the earthquakes.

The Turkish Ministry of Justice has ordered the establishment of Earthquake Crimes Investigation Departments in each city and the appointment of prosecutors to bring criminal charges against those deemed responsible for approving and constructing the buildings in question.

For Serter, it is now essential to identify all buildings that were approved and constructed prior to the latest regulations. “It is now high time to identify each of them and take urgent steps to retrofit them to quake-resilient standards,” he said.

Meanwhile, the Chamber of City Planners has called on local authorities to designate clear assembly points where the public can gather safely when earthquakes strike in the future. It is believed that several such open spaces have been transformed into shopping malls in recent years.

“We should be able to build cities where we can live for centuries,” Serter said.

“Earthquake resilience is surely important. But we should also view urban planning from an urban-level perspective and not just focus on buildings singly.”