On April 15, after weeks of tensions, clashes broke out in the capital Khartoum, between the Sudanese Armed Forces of Abdel Fattah Al-Burhan and the Rapid Support Forces of Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, also known as Hemedti.

Videos have emerged showing passenger planes on fire on the aprons at the city’s international airport, while fighter jets fly overhead. Buildings can be seen riddled with bullet holes and the roar of artillery is heard across the capital.

“The sudden eruption has disrupted life in the capital city,” Abdullah Mukhtar, a resident of Khartoum, told Arab News. His family home has been without electricity since the fighting began.

He said: “Between 70 and 80 percent of people in the capital are daily wage workers, and if they lose their wages, they’ll have to provide somehow, and as we heard and saw, there’s much looting. The neighborhood is in total darkness as well as nearby areas.

“The supermarkets are deserted and looted, and the people are experiencing one suffering after another. Frankly, there is no assistance whatsoever provided anywhere in the city except through some citizen initiatives. It’s a war zone and it’s very dangerous.

“I haven’t seen any humanitarian assistance from either side, nor have I seen any international organizations, which is understandable. How can they reach the capital when the airport has been deemed technically not suitable for landing aircraft?”

Millions of Sudanese civilians, now caught in the crossfire between the two rival factions, were already in desperate need of humanitarian assistance, much of which has been suspended since the 2021 military coup.

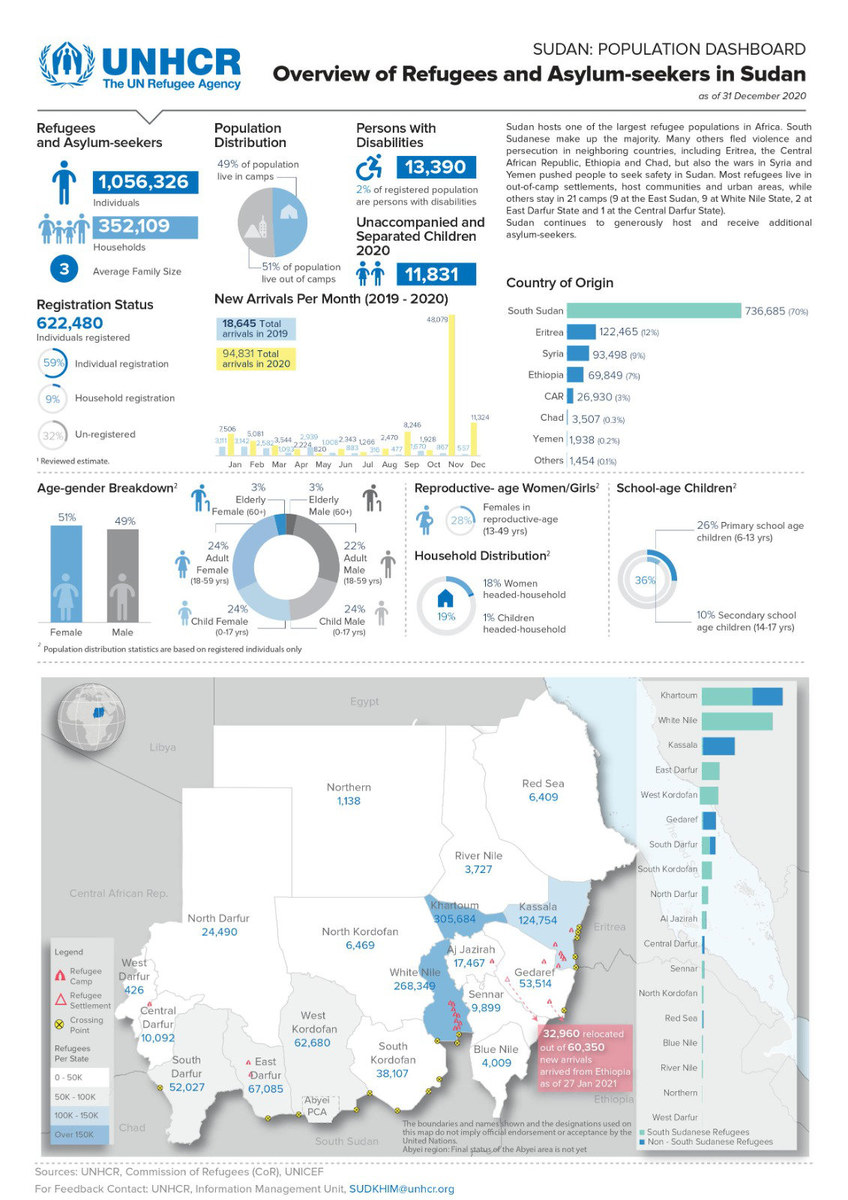

Thousands have left the capital and many are still trying to flee the violence. The UN refugee agency said on Thursday that between 10,000 and 20,000 people have fled Sudan’s western Darfur region in the past few days, seeking refuge in neighboring Chad, a nation that already hosts more than 370,000 Sudanese refugees from Darfur.

For years, Sudan’s humanitarian situation was in a precarious state due to decades of sanctions, economic deterioration, intercommunal violence, extreme weather events linked to climate change, and political turmoil.

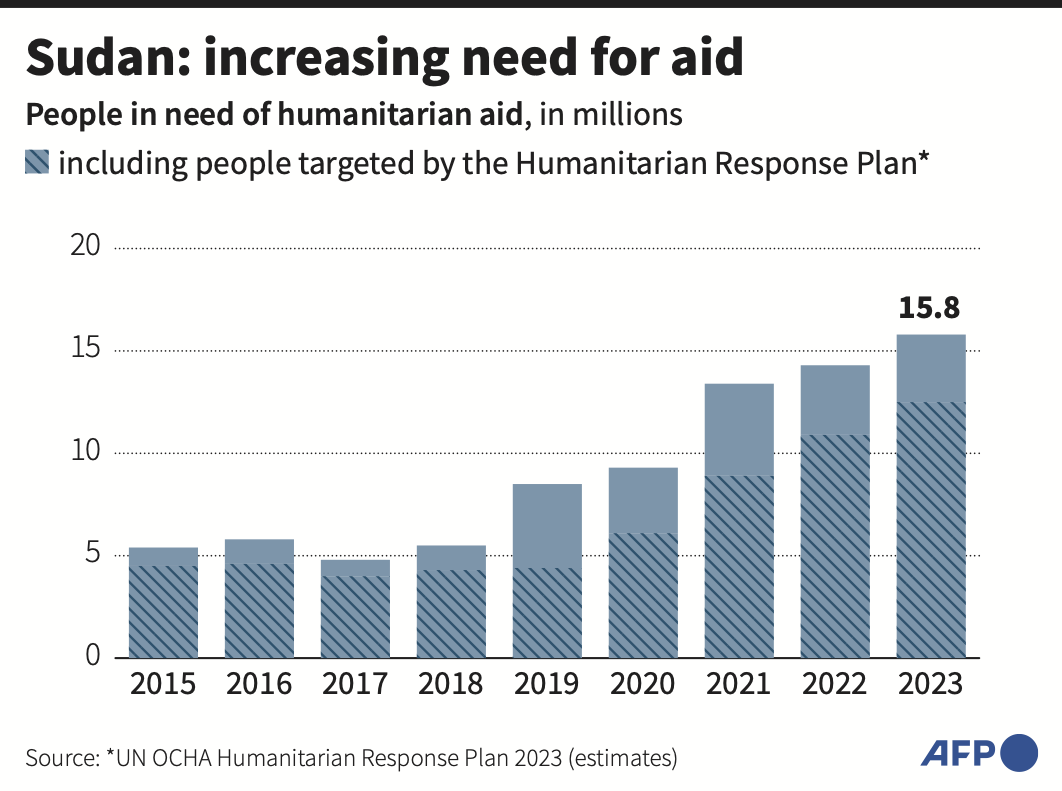

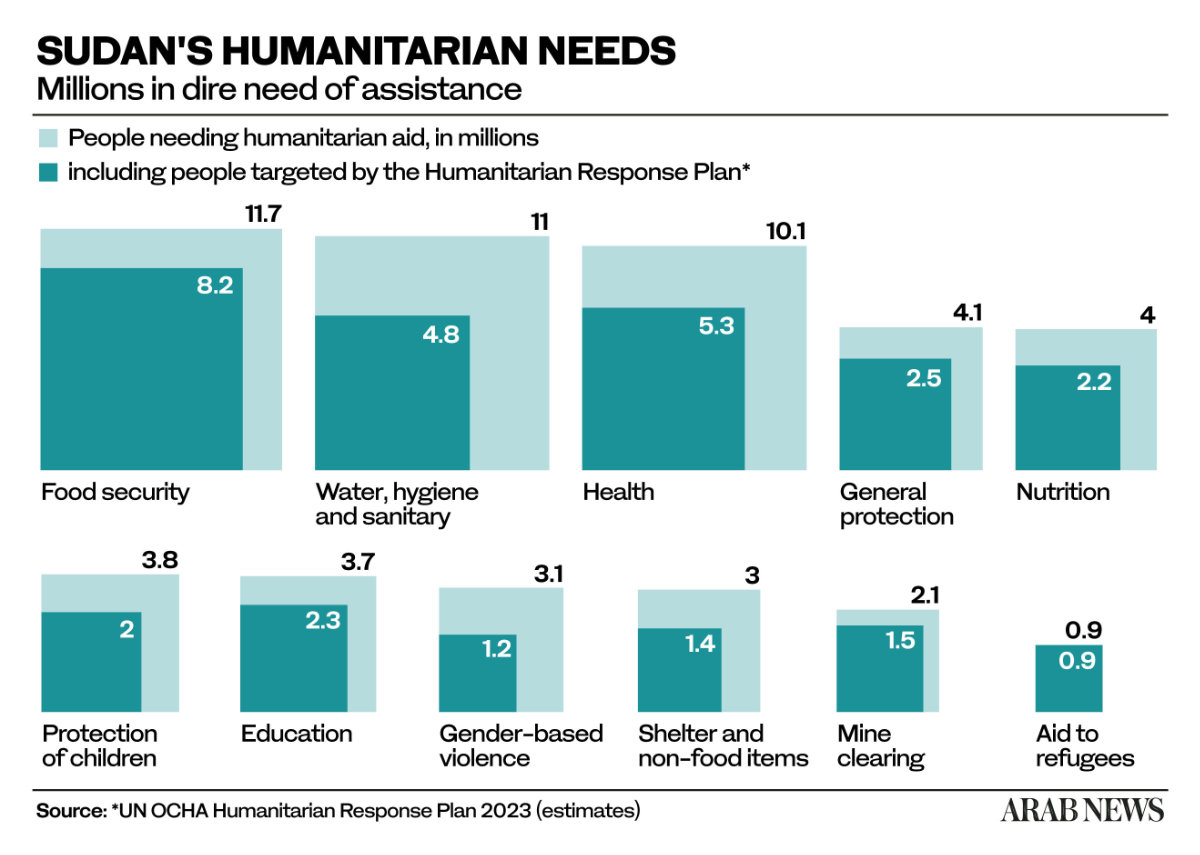

Even before the latest bout of fighting, the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs estimated around 15.8 million people among Sudan’s 45.6 million (2021) population would require humanitarian assistance in 2023, up from 1.5 million in 2021.

Of these, around 11 million required emergency assistance for life-threatening conditions related to physical and mental well-being.

Aid officials now fear the situation will grow even worse.

“I am most concerned about the potential for the current conflict to spiral into a full-blown civil war with other regional actors getting involved and supplying further weapons. This would not only lead to more civilian deaths, but also cut off access to aid for millions already in need,” Daniel Sullivan, Refugees International’s director for Africa, Asia, and the Middle East told Arab News.

“Fighting, shelling, and aerial bombardments in urban areas have caused scores of civilian deaths and cut people off from food, water, and access to medical care. Some progress had been made in providing aid and addressing accountability and preparations for return to civilian rule, but the latest violence has destroyed any positive momentum. Perhaps most worrying, the fighting has cut off aid groups from reaching millions of people already in need of assistance,” added Sullivan.

As an advocacy group, Refugees International does not have humanitarian operations in Sudan. Sullivan said there was some concern for local and international partner groups which had been forced to suspend activities and, in some cases, had come directly under fire.

He added: “The fighting in Sudan has cut off food delivery and driven aid organizations to suspend their activities and could put millions more in danger of food insecurity.”

On April 19, Sudanese Ministry of Health officials warned of a “total collapse” as 16 hospitals went out of service. According to OCHA, hospitals in Khartoum were running out of medical supplies because of looting and resources not being delivered.

“The government, the state, provides 1 percent of the population with the necessary services, medical and health, because the state itself is in a very fragile state, we cannot say a failed state. It doesn’t provide the necessary needs to the Sudanese people,” Ahmed Gurashi, a senior editor at Al Arabiya News channel, told Arab News.