- ARAB NEWS

- 15 Jul 2025

As former British parliamentarian Enoch Powell rightly put it, all political careers end in failure. For the same reason, Shakespeare’s tragic histories remain well worth understanding; either death or defeat overtake even the best and brightest leaders.

But, of course, some leaders fail more egregiously than others. Indeed, most political figures, even of great power countries, do little to change the dynamic of the times they live in, failing to bend the arc of history in their direction. They may have held power, but they are not ultimately historically consequential.

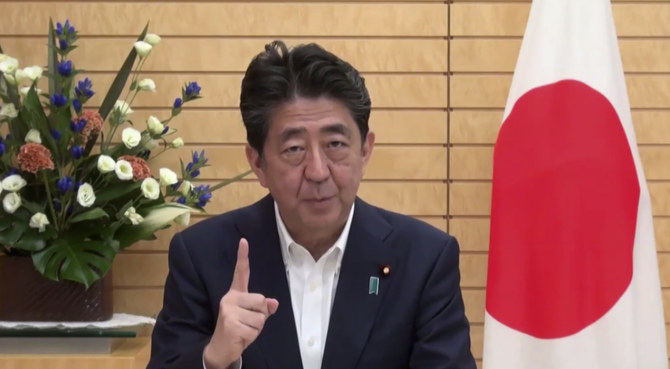

None of this can be said of Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzo, who last week announced his surprise resignation from the premiership due to a recurring debilitating illness. Abe is one of those rare leaders who mattered, who altered the course of the times he lived in.

At first glance, the Japanese prime minister seems like an unlikely historically consequential figure. Aristocratic, aloof, solid, Abe is far from being the charismatic figure that so delights historians and the general public.

Abe’s record, as is true of every historical figure, certainly contains blemishes. He failed to achieve his lifelong dream of abolishing the pacifist Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution in order to make the country a more normal great power, following on from its catastrophic defeat in the Second World War.

Abe is one of those rare leaders who mattered, who altered the course of the times he lived in.

Dr. John C. Hulsman

Likewise, Abe’s much-vaunted economic program (dubbed “Abenomics”) of ultra-loose monetary policy, increased fiscal spending, and structural reforms was a mixed bag, failing to generate the moderate rates of inflation necessary to fully pull Japan out of its two decades of relative economic sclerosis, even as the country’s debt rate ballooned. Dogged by endemic minor scandals and poor communication regarding the pandemic, the prime minister’s personal approval rating had tumbled this year.

But, for all this, Abe must be seen as a figure of historical consequence, and a successful leader at that. First, the Abe years brought desperately needed political stability to Japan. Before his second term as premier, which began in December 2012, prime ministers in the country had come and gone through a revolving door, as five had served over a period of just 5 years. In staying in place for almost 8 years — making him the longest-serving prime minister in Japan’s history — Abe gave this great power the stability it so desperately needed.

The premier’s foreign policy successes were of even greater importance. Abe’s central task has been to navigate his country through the treacherous shoals of our new era, characterized as it is by the emerging Sino-American Cold War. Instinctively realizing the nature of our world’s “loose bipolar” structure — a global system that allows great powers such as Japan, Russia, the EU, India, and the Anglosphere countries great room for maneuver — Abe took advantage of this new reality to both tame the US and to organize Asian regional balancing against an increasingly powerful China.

Abe became known as “the Trump whisperer,” so adroit was the premier at handling the American president. When Donald Trump abrogated the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP), Abe adroitly filled the diplomatic breach. The TPP, a highly ambitious free trade accord designed to more closely economically knit the Pacific Rim together around a non-Chinese locus, was as much a geopolitical move to counter Beijing’s burgeoning power in Asia as it was an economic measure.

It was for these strategic reasons that Abe salvaged the accord. In 2017, working deftly behind the scenes, Abe took the lead in reconfiguring the pact as the Comprehensive and Progressive Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), with all 12 other TPP signatories staying on board. Almost on his own, the prime minister used the CPTPP to balance against China’s increasingly expansionistic designs.

Mirroring his geoeconomic successes, history will also credit Abe with organizing regional geostrategic balancing against China. During his earlier, brief stint in power in 2006-07, the prime minister had developed the Quadrilateral Initiative, or “the Quad,” as a nascent geostrategic grouping of democracies (Japan, India, Australia, and the US) that was designed to deter Chinese adventurism in the Indo-Pacific.

While the Quad amounted to little at the time, history — in the form of increased Chinese strategic aggressiveness — has vindicated Abe’s far-sighted vision. Fostering close personal ties with Prime Minister Narendra Modi of India, Abe has left in place a rejuvenated Quad, the institutional beginnings of the organic Asian regional pushback against Beijing’s threatening rise.

Like all of history’s successes, Abe has not ignored the inconvenient facts in front of him. While Japan on its own remains a great power, economically it has been overtaken by China, even as its declining population is 10 times smaller than Beijing’s. Rather than ignoring reality, the prime minister has skillfully played the only cards available to him, ensuring through both geoeconomic and geostrategic alliances — the CPTPP and the Quad — that these political risk dangers could be overcome. This is Abe’s great strategic achievement, and history will fondly remember him for it.

Dr. John C. Hulsman is the president and managing partner of John C. Hulsman Enterprises, a prominent global political risk consulting firm. He is also senior columnist for City AM, the newspaper of the City of London. He can be contacted via chartwellspeakers.com.