- ARAB NEWS

- 15 Jul 2025

In November 1994, I published an eight-part series of articles about the history of the Jews in the Arab world in Asharq Al-Awsat, a sister publication of Arab News. That series was appreciated by many but criticized by some, including a veteran Arab journalist who wondered why I wrote something about “our enemies,” and what was the point of “knowing anything about them.”

This attitude I found a little strange from someone who, unlike me, must have known many Jews prior to the establishment of Israel. I can appreciate that people who were born after 1948, and opened their eyes on politics in the 1960s and 1970s, may feel anger and bitterness toward Israel; less so toward the Jews as a people.

However, for those who were adults before 1948, I expected many would have different narratives, if not different feelings.

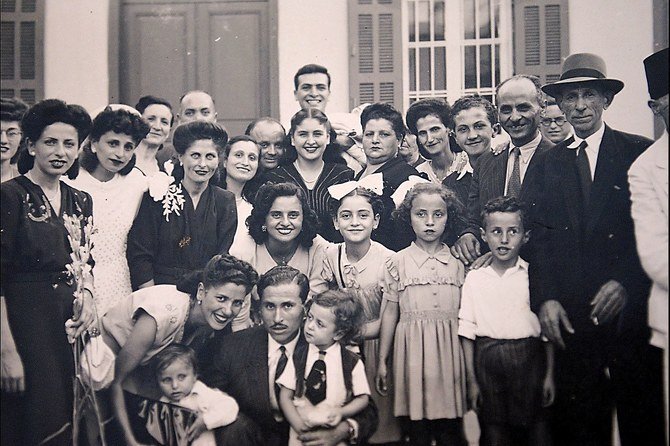

In Lebanon, where I was born and lived until 1977, I recall chats with my father and maternal grandfather about the history of our village and the Shouf District in Mount Lebanon province. From their reminiscing, I learned that, in the early 20th century, two Jewish silversmiths had lived in my village. They never recalled their surnames, but they were known in the village as the “Jewish” Amin and Saleem. They lived in peace with their neighbors for years.

The story of Dawood Bakhkhour (Bikhor) was different. I knew him personally and remember that he lived in a neighboring village until the 1970s. I also remember his wife, who predeceased him and was the leading make-up lady for the brides of our district in the days before beauty salons.

After the passing of his wife, Dawood became the only Jew living in that village, or indeed the whole district. Neither his appearance — with his “sherwal” and felt cap — nor his accent distinguished him from other villagers of his age group. His wife, as far as I can recall, came from a different background. She was a red-cheeked blonde lady with a distinct Damascene accent.

Years after her death, my mother told me about the day Mrs. Bakhkhour came to visit my grandmother (her mother) and told her that the wife of Damascus’ chief rabbi was passing through our village on her way to visit the wife of Sidon’s chief rabbi. She then kindly requested if my grandmother would honor her by welcoming the rabbi’s wife, adding: “I shall be proud to introduce her to the respectable families whose homes I frequent.” The visit took place, to the great delight of Mrs. Bakhkhour.

The founding of Israel by non-Arab Jews caused the initial damage to the trust and goodwill that had long existed between Arab Jews and their compatriots.

Eyad Abu Shakra

Later on, I got to know more about the Jews of Beirut. I remember there were fellow students at the university from the Attiyeh and Mezrib families. Many leading merchants in downtown Beirut were Jewish, especially in Souq Al-Bazarkan and Bab Idriss in the street directly behind the imposing Beirut municipality building, popularly called “Wara Al-Baladiyyeh” (behind the municipality). Among the leading names were Safdie, Qatri, Isaac and Menahem Saad, Isaac Panjel, Hakim-Dwek, Politi, Picciotto, and many others.

Furthermore, the bus journey between the National Museum — a stone’s throw from our home in east Beirut — to Ras Beirut in the western part of the city passed by two Jewish landmarks. The first was a stop near the Jewish cemetery overlooking Damascus Road (Tariq Al-Sham) in Ras Al-Naba’ neighborhood, while the other was in Georges-Picot Street, which is the northern boundary of Wadi Abu Jamil, Beirut’s Jewish neighborhood. The return route eastward passed through France Street in the southern part of Wadi Abu Jamil, where I recall a bus stop near Selim Tarrab School.

Those days were cut short by the Lebanese Civil War, which drove me to leave Lebanon and reside in first Saudi Arabia, then the UK.

In the UK, and later during my frequent travels to the US, I met many Jews from Lebanon and other Arab countries. In London, I knew a university colleague from the prominent Sudanese El-Eini family, as well as two prominent Iraqi Jews, Meir Basri and Yeheskel Kojaman (Hasqeel Qojman), who wrote valuable books about Iraq and its history, culture and music. They were all proud to profess their Sudanese and Iraqi identities.

Rosa El-Eini did not live in Sudan, but she told me that her family never chose to leave Khartoum, as they were well to do there. However, they became worried about their safety after the 1967 war and the subsequent Khartoum Arab League summit, which rejected any kind of dialogue with and recognition of Israel. Feeling threatened, they left for the UK, where they resided in Sussex.

Basri and Kojaman belonged to a different generation. They were active members of the social, business and political circles of Baghdad. They spoke perfect Arabic, Basri enjoyed classical Arabic poetry and literature, and Kojaman — an active anti-Zionist communist — wrote impressive works about Iraqi music and the Iraqi Jews’ contributions to it.

A similar attachment to Arab roots I discovered in Prof. Jack Sasson, who I met in the US when he taught Near Eastern classics at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, later joining Vanderbilt University. Sasson is first and foremost a proud Syrian. He enjoys speaking in Arabic with any Arab he meets. He was born in Aleppo, leaving for Beirut only in the late 1940s after the troubles that badly affected the formerly prominent Jewish community there. He then left Beirut for the US, where he still lives now, but never forgetting his roots as a Syrian and as a Jew.

He said: “I am proud of my Syrian heritage, proud to be Syrian and Aleppine. Whenever I attended conferences and was introduced to my Arab hosts or colleagues, they would automatically talk to me in English. However, I always stopped them short by saying: Please, I am Syrian and speak Arabic.”

In conclusion, I would say that the founding of Israel by non-Arab Jews caused the initial damage to the trust and goodwill that had long existed between Arab Jews and their compatriots. Arab Jews were never at the forefront of the Zionist movement. They were either already living in the Near East or were driven to North Africa during the “Reconquista,” together with Muslims from Iberia. In Morocco, they were actually protected and felt safe. Furthermore, they were already living with fellow Semites, so the notion of anti-Semitism that appeared in Europe did not apply to them.

However, the 1948 and 1967 defeats, which fueled nationalist fervor and later guerrilla resistance movements, drove the whole region into a vicious circle of distrust, dehumanization and demonization, which has weakened all voices of moderation and helped extremists on both sides of the Arab-Israeli conflict.