William Mullally, Dubai

This was a year of transformation, both for film as a business and film as an artform. While the ascension of streaming services has been the prevailing narrative globally, streaming is not the only positive trend in our region. Cinema-going culture in the Middle East is stronger than ever before, and no one is fueling that rise more than the people of Saudi Arabia.

While the history books will always show 2018 as the year Saudi Arabia lifted the ban on cinemas, 2019 has a largely untold but more important story — one of astounding growth. Major cinema chains including VOX Cinemas and AMC have rushed to accommodate demand, opening world-class movie theaters across the country, with many more to come. With 113 screens currently, the Kingdom already has more screens than Bahrain’s and Kuwait’s 103 screens — although it is still dwarfed by the UAE (598) and Egypt (238). Most stunningly, box office in Saudi Arabia has grown more than 1000 percent over the last year, meaning it is now the second-largest market for film in the region in only its second year of cinema, eclipsed only by the UAE.

Western blockbusters are still the main driver for cinemagoers, but Arab cinema — especially Saudi cinema — is poised for a new golden age after a stellar year for filmmakers and actors of Arab origin.

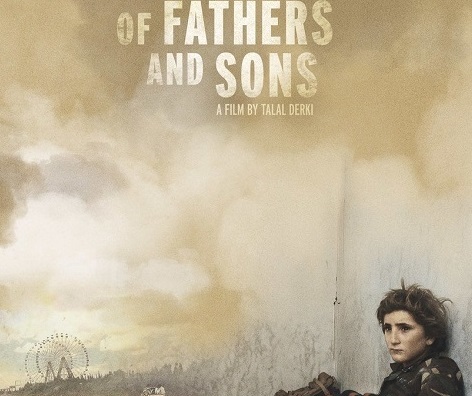

In February, Rami Malek became the first Arab man to win Best Actor at the Academy Awards for his portrayal of Freddie Mercury in “Bohemian Rhapsody,” while Lebanese filmmaker Nadine Labaki became the first Arab woman to have her film nominated for best Foreign Language film with “Capernaum,” which also broke global box-office records for an Arab film. Not to be overshadowed, Syrian director, producer and screenwriter Talal Derki was nominated for Best Documentary Feature for his incredible film “Of Fathers and Sons.”

As the world watches the current events in the region, the Middle East’s films are the best place to discover its true soul, as well as to discover the real people caught up in the region’s struggles — from the most extreme circumstances to more-commonplace difficulties. Films from Saudi Arabia and the broader region, both fiction and documentary, captured the Arab world with an unflinching eye, a big heart, and a critical hand.

As pieces of art, both “Capernaum” and “Of Fathers and Sons,” released in Middle Eastern cinemas in 2019, found their extraordinary power in Arab children. Often so close to real life it hurts to watch, “Capernaum” exposed the world of the extreme poor and refugees in Lebanon, with a young Syrian refugee named Zain Al Rafeea starring as a poor Lebanese boy struggling to survive. “Of Fathers and Sons” was the more terrifying film, following a member of a militant extremist group and his young children who are slowly indoctrinated into becoming terrorists themselves. Both are harrowing to watch, yet empathetic and vivid, featuring some of the most resonant scenes in the history of Arab film.

As the year progressed, a number of the most notable Arab films kept the spotlight on children. “For Sama,” a documentary directed by Waad al-Kataeb, finds the director speaking directly to her infant daughter Sama, who was born during the collapse of Syria, recounting the story from the start of the conflict in Aleppo until she and Sama’s father were forced to flee. Its most haunting moment is an unflinching look at the birth of a child as bombs drop overhead, as the newborn goes from unresponsive to suddenly and miraculously full of life.

Saudi filmmaker Shahad Ameen’s fictional film “Scales” also follows a young girl, but rather than highlighting a regional conflict or extreme poverty, Ameen’s film is a metaphorical dark fantasy that elucidates the struggles of women in Arab society. In her gorgeously-shot film, co-produced between Saudi and the UAE, a young girl living in a fishing village struggles between life among the hunters who raised her and her sympathy for the creatures they hunt —mermaids who live in the dark waters beyond the village’s shores. It’s an unmistakable piece of both style and substance that shows Ameen is already one of Saudi Arabia’s most talented artists.

The Kingdom’s most-lauded filmmaker, Haifaa Al-Mansour, premiered her latest film, “The Perfect Candidate,” at the Venice Film Festival (it is yet to appear in Middle Eastern cinemas). It also addresses the status of women in the Kingdom, following the trials and tribulations of an aspiring female politician navigating male-dominated society as she runs for office in her local city elections. And Raed Alsemari’s excellent short film “Dunya’s Day” won a major prize at the Sundance Film Festival for its brave portrayal of a young Saudi woman who is both unlikeable and worthy of sympathy, signaling that not only are women rising in prominence in Arab film, the characters they play are evolving too.

While it was undeniably an excellent year for the Arab film industry, there is, of course, a long way to go before it is even playing the same game as Hollywood or Bollywood — let alone in the same league. What dominated cinemas and the conversation around film in 2019 were blockbuster franchises — particularly the superhero genre.

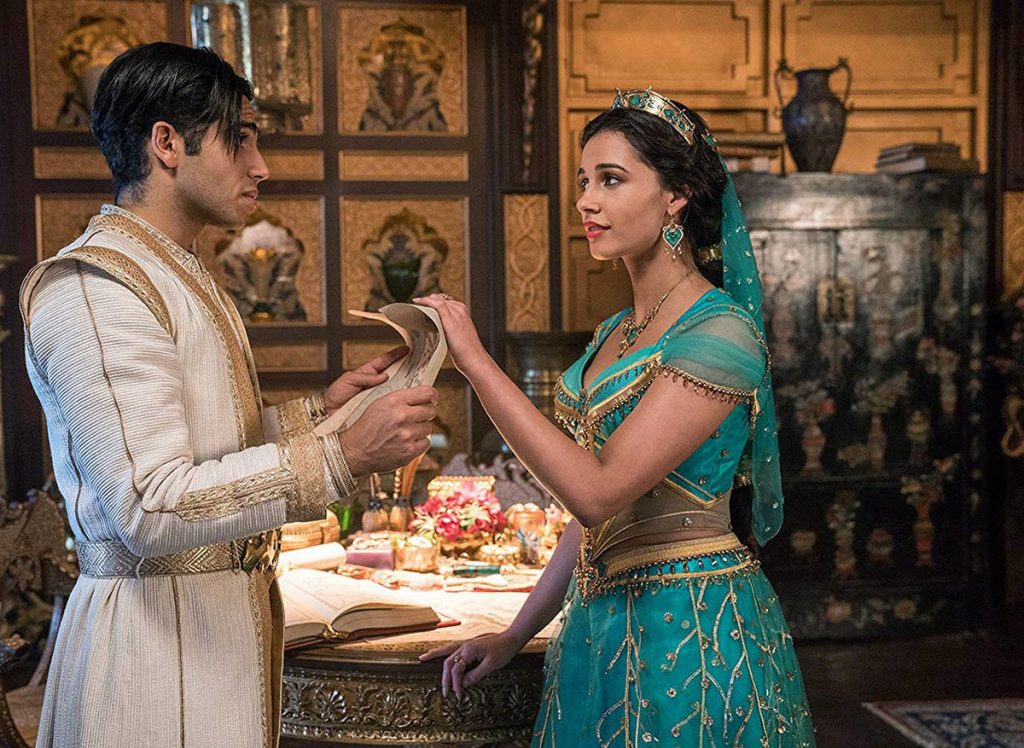

Marvel continued to put out hit after hit, with “Captain Marvel,” “Avengers: Endgame,” and “Spider-Man: Far from Home,” while “Joker” shocked the world with a brutal R-rated tale that grossed over $1 billion. Disney dominated cinemas — in addition to its Marvel output, it also crossed $1 billion in grosses with “The Lion King,” “Toy Story 4,” “Frozen 2,” and “Aladdin.” (The just-released “Star Wars: The Rise of Skywalker” will almost certainly join them, too.) In fact, “Joker” was the only film not released by Disney to pass that once-impossible milestone — while other once-golden franchises such as “Charlie’s Angels,” “Men in Black,” and “Godzilla” fell flat. It seems only Disney is currently immune to franchise fatigue.

“Aladdin,” a massive hit in the Middle East and across the world, was by far the most popular piece of entertainment with an Arab star this year, with Egyptian-Canadian actor Mena Massoud bringing the classic animated character to life. While the film in no way tried to show a realistic or modern portrayal of the Middle East, it was a deliberately multicultural and joyful movie that depicted the region as a world rich in beauty, art, and tradition. Since the film’s release, the real-world story has not been entirely positive, though; Massoud has since publicly complained that he has not gotten an audition since the film’s release, suggesting a still-steep hill to climb for young stars of Arab origin in Hollywood not named Rami Malek.

Perhaps the most ironic (and far-reaching) revelation of the year for cinema was that if you wanted to see some of the best films by the best filmmakers working today, you had to stay at home. Martin Scorsese’s “The Irishman,” Noah Baumbach’s “Marriage Story,” and Fernando Meirelles’ “The Two Popes” all skipped Middle Eastern cinemas entirely and made their way directly to Netflix — and all have picked up Golden Globe nominations for Best Drama.

Even as cinema culture remains strong in the Middle East, for film-lovers and filmmakers the future, it seems, will be just as busy online as it will on the big screen.