- ARAB NEWS

- 27 Apr 2024

Carla Chahrour

The King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies (KFCRIS) in cooperation with the Embassy of Japan in Saudi Arabia organized on February 19 a lecture exploring the recent trends and advanced features of urban development in Japan that are globally applicable.

The workshop featured presentations from established academics and industry specialists including an Associate Professor at the Department of Urban Engineering from the University of Tokyo Dr. SETA Fumihiko and the Chief Executive Officer of the Special Olympics in Saudi Arabia Dr. Heidi Alaudeen Alaskary.

In his opening remarks, Hirofumi Miyake, the Deputy Chief of Mission at the Embassy of Japan in Saudi Arabia discussed the major elements that need to be taken into consideration when planning developments in cities. These include ensuring that life in the city is inclusive of all members of society, including children, the elderly and those with disabilities, while simultaneously making it sustainable for future generations.

“Japan has experienced rapid urbanization during the last century and has faced a variety of problems resulting from urbanization and we have successfully overcome some of them. Now, Japan is working on the monumental task of hosting the Olympic Games in Tokyo. To prepare for that, not only did it include developing facilities and accommodation, but also city planning such as building new traffic networks and other infrastructures needed to receive thousands of athletes and visitors from all over the world,” Miyake said

“I believe that all of the knowledge and experience that we have will benefit Saudi Arabia. Under the Vision Saudi 2030 we are witnessing speedy social and economic transformation going on. Last month Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman unveiled plans to increase the population of Riyadh to 15 million and raise Riyadh to one of the ten richest cities in the world. I feel that Japanese technologies can contribute to the development of the kingdom for the future through participating in these projects,” Miyake added.

Dr. SETA Fumihiko, a distinguished scholar on urban development presented an informative lecture on the topic.

“Based on the statistics of the United Nations Tokyo Metropolitan region is still the biggest populated megacity, with a population of 37 million people. The second most populated city in Japan is Osaka, sometimes called Kansai together with the surrounding prefecture which has a population of 19 million people,” SETA said.

He explained that the four main characteristics of urban development in Japan include: Management, transit-oriented development (TOD), land readjustment and smart city.

“Firstly I’d like to explain the contemporary trend of urban development, which is represented by the word ‘management.’ Formerly, urban development was used for limited purposes, where projects only focused on single-use development or construction. After several decades, the tendency has changed or the notion of urban development has grown from single-use construction projects to mixed use for management purposes and construction projects to enhance the value of property of a real estate and the management of a whole area or district,” Seta said.

This lead to the inception of another trend in contemporary urban development in Japan is “Area Management” which, according to Seta, can be translated to a “city center” where real estate and infrastructure developers seek to not only provide new functions like retail shops, restaurants, hotels or condominiums to their areas, but also attempt to enhance the attractiveness of these areas by proper management.

Transit-oriented development help enhance the use of public transport throughout the country. In urban planning, a transit-oriented development is a type of urban development that maximizes the amount of residential, business and leisure space within walking distance of public transport. It promotes a symbiotic relationship between dense, compact urban form and public transport use.

“A significant characteristic of urban development in Japan is the abundance of public transportation, which is present not only in the central city but also in the suburban areas through the use of the method of transit-oriented development,” Seta said.

This was demonstrated by the provision of pictures of the Futako-tamagawa Station, which shows a”‘typical suburban TOD.”

The Futako-tamagawa train station, located in the southwestern suburbs of Tokyo. (Shutterstock)

The Futako-tamagawa train station, located in the southwestern suburbs of Tokyo. (Shutterstock)The station is surrounded by buildings that are developed by private railway companies and are used for different functions including, commercial and residential, as well as water and green spaces that exist in harmony with the surrounding natural environment.

The allocation of such facilities was purposely done in order to attract members of the population and enhance the use of public transport in that area, according to Seta.

This Futako-tamagawa Station redevelopment project in Japan illustrates the use of land value capture with transit-oriented development employed by Tokyu Corporation, one of Japan’s major private railway operators, which increased ridership on the Den-en-toshi line, generated steady cash flows, and recouped investment costs, according to the World Bank.

Located in the southwestern suburbs of Tokyo, on the Den-en-toshi Line, a major commuter line providing access to central Tokyo and one of Tokyu Corporation’s most crowded commuter lines. The line was developed during the 1940s-1980s and coincided with the rapid urbanization of Tokyo, which generated a strong demand for both, new housing areas and public transport to the center of Tokyo.

Tokyu Corporation launched the Futako-tamagawa Station redevelopment project in 2000, which was one of the largest redevelopment projects in Tokyo. The project was completed in 2015 and formed a new center for residential, commercial, residential and leisure activities, with urban accessibility around Tokyu’s railway station.

The redevelopment project was designed to reflect the demographic changes occurring in Japan and Tokyo at the time, as well as the need for strategically-designed cities to attract workers and other members of the population, by including a number of unconventional service facilities.

Another example of transit-oriented development provided by Seta includes Marunouchi, a central business district (CBD) area that faces the Tokyo Station, was mainly used to tenant company offices. However, since there were only company offices, the area was left empty on weekends, lacking a vibrant atmosphere.

Marunouchi was then redeveloped to include multiple urban functions, such as hotels, museums and commercial spaces. The Marunouchi Building was one of the first redevelopments of this type and the success of the project prompted the renovation of other buildings to gain more floor space for shops and restaurants in order to attract more people into the area.

Tokyo station, a railway station in the Marunouchi business district of Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan. (Shutterstock)

Tokyo station, a railway station in the Marunouchi business district of Chiyoda, Tokyo, Japan. (Shutterstock)“One unique characteristic of japanese companies in the metropolitan area is that they are financially independent, where more than half of the finance is from real estate and retail built around the station. This is a new variation of business sources of railway companies and such characteristics enable TOD in the case of Tokyo and Osaka,” Seta added.

The third unique characteristic of urban development in Japan can be seen in the suburban areas and is called “land readjustment” which is a tool used by local governments that allows them to perform regeneration projects that reshape the land in a more efficient layout and to build out the public infrastructures through increased land values while engaging and involving the original landowners as stakeholders.

The land readjustment approach enables the assembly and planning of privately owned land that is located in an area immediately adjacent to a city or urban area, as well as the delivery of infrastructure and services on such land. Using this approach, the government assembles portions of various privately owned land to designate spaces for public infrastructure and services such as roads.

At the end of the process, the landowner is left with a land that is of smaller size, except that the new land is of a higher value because it is now serviced urban land.

“Originally, land was cultivated by many farmers, but then the movement of urbanization was coming to this area. The roads were very narrow and insufficient for caes to pass through.

Thus the government tried to restructure the land, but instead of purchasing all the land, land reconstruction was conducted. This was done through governments conviving land owners to allow them to develop large roads around their land. Although such activities reduced the size of the landowners’ land, they agreed to such adjustments as it increased the value of their land.

Surprisingly, around 27%, which means one fourth of all built up areas in Japan, has been developed by land readjustment projects,” Seta elaborated.

Seta then explained the growing concept of ‘Smart Cities’ or ‘Internet of Things’ (IOT), which include electricity optimization and the creation of smart grid ideas to modernize the electricity delivery system.

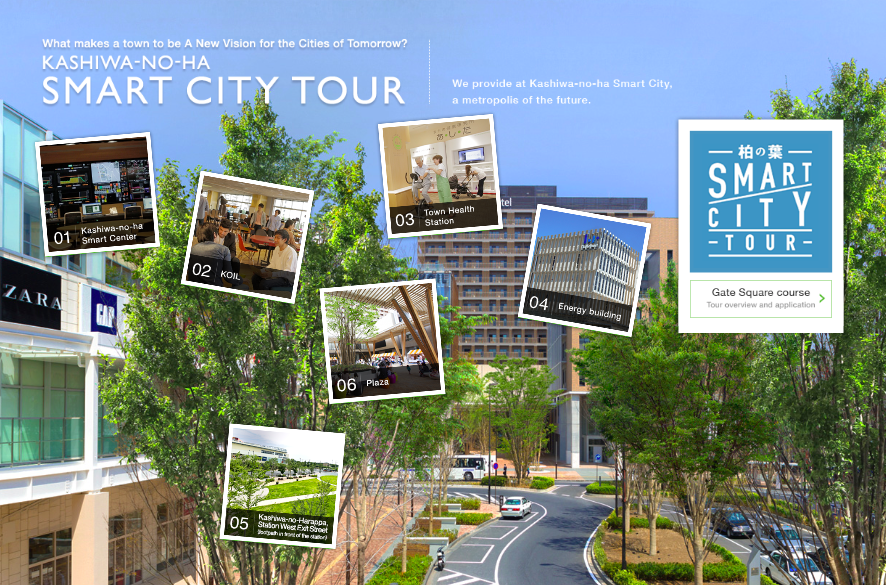

This was done through providing the example of the “Kashiwa-no-ha Smart City,” which is one of the representative cities that introduced the smart cities concept, in the city of Kashiwa, Chiba Prefecture.

The Kashiwa-no-ha Smart City is based on a partnership involving the public, private, and academic sectors that has been designed to embody a new vision for the future of Japan that is environmentally sustainable and human-friendly.

The Kashiwa-no-ha Smart City, in the city of Kashiwa, Chiba Prefecture. (kashiwanoha-smartcity)

The Kashiwa-no-ha Smart City, in the city of Kashiwa, Chiba Prefecture. (kashiwanoha-smartcity)In an exclusive interview with Arab News Japan after the lecture, Seta elaborated on the concept of Smart Cities, IOT and the challenges that urban development in Japan is currently facing.

Seta said that the three most pressing issues of urban development in Japan today are: depopulation, natural disasters and the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic.

The demographic shift toward aging and declining society has forced Japanese cities to take a new look at the concept of urban planning. This means that Japan has to develop new strategies to ensure that the infrastructure is suitable for the upcoming population.

“Japan is maybe the first country which will experience a very long-term population decrease. For example, today I explained about land readjustment, but the precondition of this method is population increase. So now in most areas land readjustment can no longer be used in Japan as demand has reduced, so it is difficult to apply. So we have to think about a new urban development method,” Seta said.

While land readjustment programs were implemented to make urban development more efficient during the period of rapid urbanization, given that the land available for urban development in Japan is limited, the onset of depopulation means that new, innovative plans and strategies need to be created.

The second issue urban development in Japan is facing has to do with natural disasters.

Japan has lived with natural disasters since ancient times. The national and local governments repeatedly attempt to upgrade the alert systems, emergency maps and urban infrastructure after catastrophes in order to mitigate damage caused by natural disasters.

“Japan suffers from many kinds of natural disasters, from earthquakes, floods, typhoons, and tsunamis, and landslides. We have to prepare everywhere against natural disasters and urban development has to think about this. For example, two days ago, Tokyo suffered from a relatively big earthquake. At that time, electricity was not shut down, but if electricity was to shut down, all the business activities would have to stop. So now many companies in Japanese urban development areas are increasingly thinking about “Business Continuity Plans – BCP” which will allow business to continue to function even if a natural disaster were to shut down electricity,” Seta said.

“This is very important especially for global companies. Today urban development projects are trying to provide the infrastructure services against natural disasters and related problems, such as electricity shutdowns or water shutdowns,” Seta added.

Business Continuity Plan is the process of creating systems of prevention and recovery to deal with potential threats to a company. In addition to prevention, the goal is to enable ongoing operations within an organization before and during the occurrence of a natural disaster. In order to do so, businesses are preparing “big electric chargers” that can be used to allow the organization to continue operating during long term electric shutdowns, according to Seta.

The third issue urban development in Japan is facing involves the implications that the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic has had on the social infrasturcture.

Similar to many other countries, COVID-19 has caused people in Japan to swap the city-life for the country-side, where the population density is less and the settlements are more dispersed.

This poses a new challenge for urban development plans in Japan that seek to have ‘compact cities’ where the places to live, work, learn, and play were integrated into an area within walking distance in order to ensure affordable and safe mobility for elderly citizens while simultaneously improving Quality of Life.

“The population density of Tokyo and Osaka is very high, in a sense, gathering a large amount of people in these areas was a positive concept for Japan. However, such areas are not good for COVID-19 due to the ability of infection to spread. It is possible that urban development should shift from planning areas with such high density and of course many real-estate companies are thinking about the so-called “new normal” and we are not sure if the new normal will deny the buildings and infrastructure seen throughout Japan’s urban areas, which are densley populated,” Seta said.

“Japanese society has been tackling energy conservation for a long time, since thirty or forty years ago oil was, and still is, the main energy source. In terms of urban development, we are thinking of ways to save energy in buildings, which would also lead to a reduction in CO2 emissions. Now, we are thinking of introducing different types of renewable energy sources, such as wind energy or solar power. But even if we were to generate such kind of energy from these sources, it’s not easy,” Seta said.

“For example, this winter Japan was very cold, the electric energy generated by the big electric companies almost reached its maximum capacity. This means that it is difficult to generate enough energy from renewable sources to supplement such situations. Moreover, in winter it tends to be colder at night, and in solar power energy is mostly generated in the daytime. Such a gap between generation and consumption exists in many cases. This issue is not only in Japan, but one faced all over the world, regarding how to optimize energy generation and consumption in the daytime and the night or in the summer and in the winter.” Seta added.

The gap between generation and consumption and the inability to efficiently store energy generated by sources such as solar and wind power, is a key issue that has hindered implementation of renewable energy sources as the main supply of domestic energy, according to Seta.

He also elaborated on the concept of “Compact Cities” which placed focus on public investment to build dense centers and sub centers and then connect these dense areas with public transportation to shift from a car-oriented society, as a method to reduce carbon emissions.

“Compact Cities” is actually a very important keyword in Japan but the main area in question for such developments are the rural areas because in rural areas the density is decreasing and many people won’t use public transportation, which is even nonexistent in some areas. On the other hand, in metropolitan areas, compact developments are already realized and this concept is currently under consideration with COVID-19,” Seta said.

Japan serves as an example of a country that has been able to build disaster- resistant, eco friendly, and inclusive cities during a period of rapid urbanization and fast economic growth. The topics discussed by Seta represent several reasons behind the resilience of Japanese cities, which stem from the fact that the country has had to overcome a variety of urban issues, ranging from rapid population growth and urbanization to an aging society.

This has equipped the country with an array of knowledge and infrastructure technologies that could contribute to finding solutions for the challenges of urbanization in other countries.