Lucas Chapman and Ali Ali

QAMISHLI, Syria: This year, the world watched in horror as the Syrian Democratic Forces and the US-led coalition rapidly mobilized to prevent what many observers viewed as Daesh’s boldest attempt yet to re-establish its short-lived “caliphate” in northern Syria.

Since its territorial defeat in Iraq in 2017 and Syria in 2019, Daesh had appeared to be a spent force, its leaders hunted and forced into hiding, its followers either detained, dead or disenchanted, and its once-sizeable war chest depleted or out of reach.

That is until January this year, when remnants of the group launched a massive and highly sophisticated attack on a prison in northeast Syria where thousands of its former combatants were being held under guard by the SDF.

With the West now focused single-mindedly on Ukraine, and the Syrian regime’s Russian allies preoccupied with activities closer to home, those on the ground in Syria warn that the threat posed by Daesh is far from over and that a resurgence could easily occur while the world’s back is turned.

On the evening of Jan. 20 the relative calm in Hasakah, a city of about 400,000 people in the eponymous Syrian governorate, was suddenly shattered by a thunderous blast when a truck laden with explosives detonated at the gates of Al-Sina’a Prison.

Moments later, hundreds of armed men attacked the facility from all sides with the clear intention of releasing about 5,000 Daesh-affiliated prisoners that were being held inside and returning them to the battlefield.

For several days, local forces clashed with the militants in the biggest battle the city had seen since Daesh was ousted six years earlier. The US-led coalition intervened using jets and drones, striking buildings where the militants were holed up. In response, Daesh fighters seized civilian properties near the prison, using their occupants as human shields.

“It wasn’t the kind of war where you know where the terrorists’ base is and you can go attack them,” Serhat Himo, a member of the local commando force that intervened on the first night of the attack, told Arab News.

“They took positions among civilians and because of this many civilians were killed by Daesh. We had to pull civilian bodies out of the homes.”

Some reports suggest that 374 militants were killed during the attack, along with 77 prison staff, 40 members of the SDF and four civilians. About 400 inmates remain unaccounted for, indicating that a significant number escaped.

In the Jan. 27 edition of An-Naba, Daesh’s online propaganda outlet, the militants claimed “several groups managed to get out of the (Hasakah) area safely and were transferred to safe areas.”

From the perspective of the SDF, which is responsible for defending the multi-ethnic populace of the Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, the extremist threat was obvious long before Daesh’s highly coordinated prison attack.

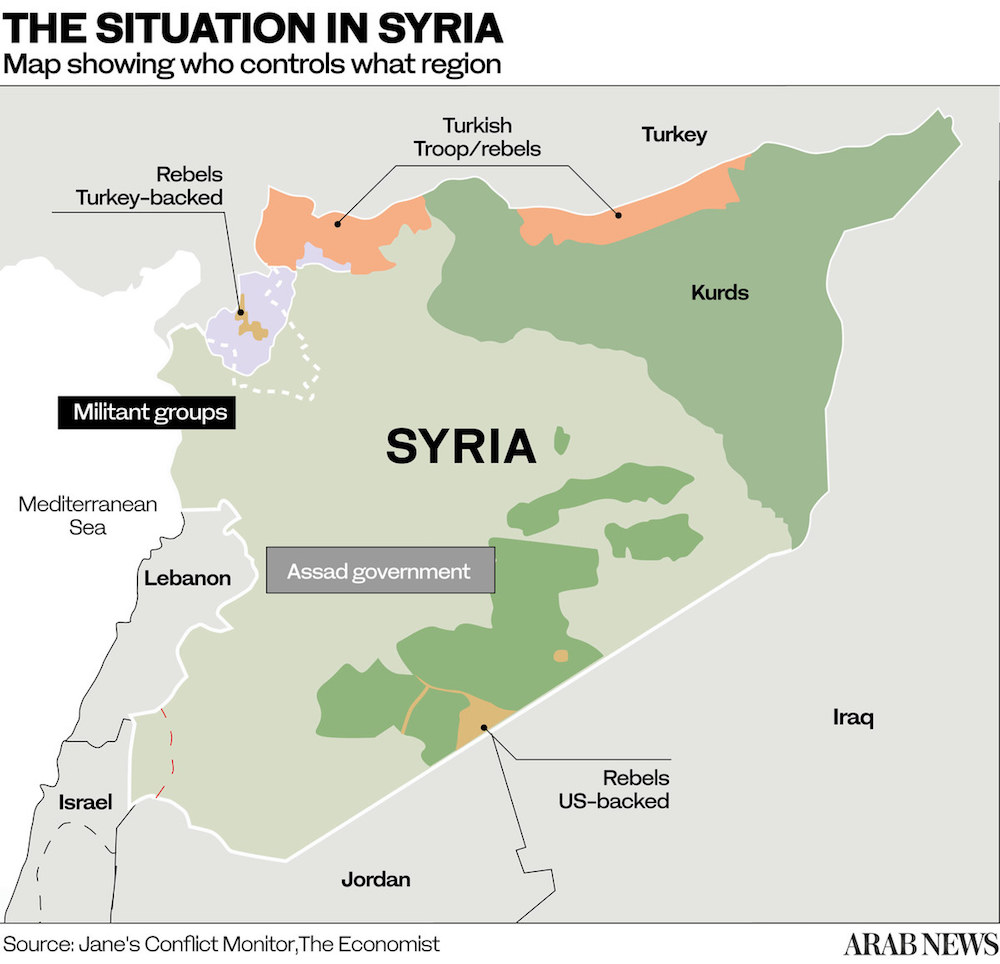

More than a decade after the 2011 uprising against the regime of President Bashar Assad thrust Syria into a state of civil war, large swaths of the country have fallen into the hands of armed groups.

Syria’s north and northwest, for instance, is controlled by an assortment of factions under the banner of the Syrian National Army, formerly known as the Free Syrian Army, and the Al-Qaeda-linked Hayat Tahrir Al-Sham, or HTS.

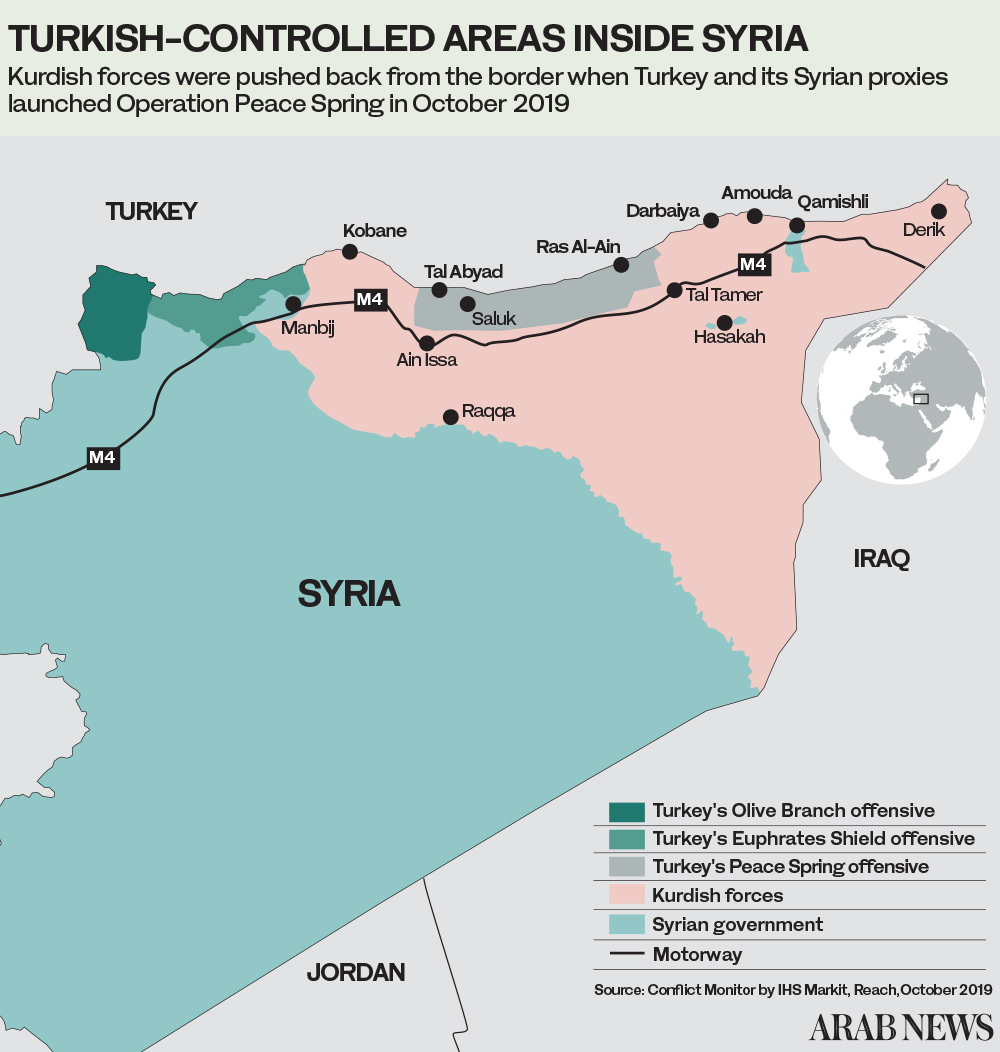

The SNA controls the district of Afrin, having seized the area from the AANES in 2018 with the help of Turkish armed forces. It also controls Ras Al-Ain and Tel Abyad, having taken these towns in 2019, also with Turkish assistance.

Turkey intervened on both occasions to remove the Kurdish-majority People’s Protection Units, known as the YPG, from areas straddling its southern border.

Ankara considers the YPG, the main contingent force within the SDF, to be the Syrian affiliate of the Kurdistan Workers’ Party, or PKK, which has fought a decades-long guerrilla war against the Turkish state in an effort to gain greater political and cultural rights for Kurds in Turkey.

Both the SNA and the HTS are known to have extremist elements among their ranks. According to local sources, Daesh remnants have used areas under rebel control to regroup and evade detection.

In October last year, a US drone strike killed Abdul Hamid Al-Matar, a senior Al-Qaeda operative, in the SNA-held town of Suluk in Raqqa province. Days later, a British Royal Air Force drone killed Daesh arms supplier Abu Hamza Al-Shuhail in Ras Al-Ain.

In October 2019, just months after the group’s defeat in Baghouz, Daesh’s former leader and erstwhile caliph, Abu Bakr Al-Baghdadi, was tracked down to the village of Barisha in an area of Idlib controlled by HTS. He killed himself and three of his children with a suicide vest rather than surrender to US special forces.

Just a matter of weeks after the attack in January on Al-Sinaa Prison, the SDF and US special forces traced Al-Baghdadi’s successor, Abu Ibrahim Al-Qurayshi, to the town of Atmah, also in Idlib. During the course of the operation, Al-Qurayshi detonated a bomb, killing himself and his family.

Daesh announced its new leader, Abu Al-Hassan Al-Hashemi Al-Quraishi, in a recorded audio message distributed online on March 11. According to Iraqi and Western security sources quoted by Reuters, he is the brother of Al-Baghdadi.

“We defeated Daesh territorially but the mentality remains,” Nouri Mahmoud, the YPG’s official spokesman, told Arab News.

“Radical terrorists from Daesh, Al-Qaeda, Levant Front, the Muslim Brotherhood and others settled in Afrin, Sere Kaniye (Ras Al-Ain) and Gire Spi (Tel Abyad).”

A report published in June 2021 by Syrians for Truth and Justice, a local human rights monitor, found there to be at least 27 former Daesh militants, including senior operatives, serving in the ranks of the SNA.

“After Daesh was defeated territorially at Baghouz, many of them fled to Iraq, regime-held areas and to areas held by Turkish-backed groups, particularly Ras Al-Ain and Tel Abyad,” Kenan Barakat, co-chair of the AANES interior ministry, told Arab News. “There, they simply changed their affiliation and joined other radical groups.”

Despite the clear threat posed by these groups, the SDF and AANES have found their resources squeezed by the closure of UN-recognized border crossings and the imposition of diplomatic and trade embargoes by Turkey, which have decimated the local economy.

“As long as there is a political and economic embargo on northeast Syria, Daesh will remain,” said Mahmoud.

“As long as these other terrorist factions continue their attacks on our regions and use these areas under occupation as a rear base, Daesh will continue to seize opportunities to reorganize itself.”

The terror group’s recent attempts at a resurgence are not confined to the incident at Al-Sina’a Prison. In the days and weeks since the attack on the jail, residents of Al-Hol detention camp, also in Hasakah, have staged repeated escape attempts.

Known as “a ticking time bomb” and “the world’s most dangerous camp,” Al-Hol is home to about 56,000 people. More than half them are Iraqi and about 8,000 are foreign nationals or the wives and children of militants from Europe and elsewhere.

The camp’s population grew rapidly in early 2019 following Daesh’s territorial defeat in Baghouz. Since then, the residents of Al-Hol have made repeated attempts at creating a kind of pseudo-caliphate within the camp.

“Those in the camp, both men and women, have tried many times to start a war in the camp,” said Barakat.

“They have started uprisings, burned tents and killed members of the Internal Security Forces. They wanted to recreate the scenario at Ghweiran (Al-Sina’a) Prison in the camp but our forces interfered and stopped them.”

Many of the children in the camp are now reaching their teenage years, having been raised with Daesh ideology imparted by their mothers. Camp administrators fear they are witnessing the coming of age of a resentful and highly-radicalized new generation of militants.

Many in the local administration believe it is only a matter of time before a major escape attempt succeeds, unless the international community acts immediately.

The AANES and SDF have repeatedly called on Western governments to repatriate their citizens from the camp and to establish special courts to try foreign Daesh members so that they can be placed into proper detention facilities.

“These Daesh members are from many countries — nearly 50 nationalities can be found among them,” said Barakat. “This is not just a Syrian issue. It is an international issue. Daesh threatens many states around the world.”

He fears there is a high probability of a Daesh resurgence unless the world sits up, takes notice and takes action.

“Victory against Daesh is a victory for everyone,” he added.