LONDON: With bated breath, the world awaits Iran’s promised retaliation for last week’s suspected Israeli airstrike on its embassy annex in the Syrian capital Damascus. Whatever form Teheran’s revenge takes, there is mounting public fear it could trigger an all-out war.

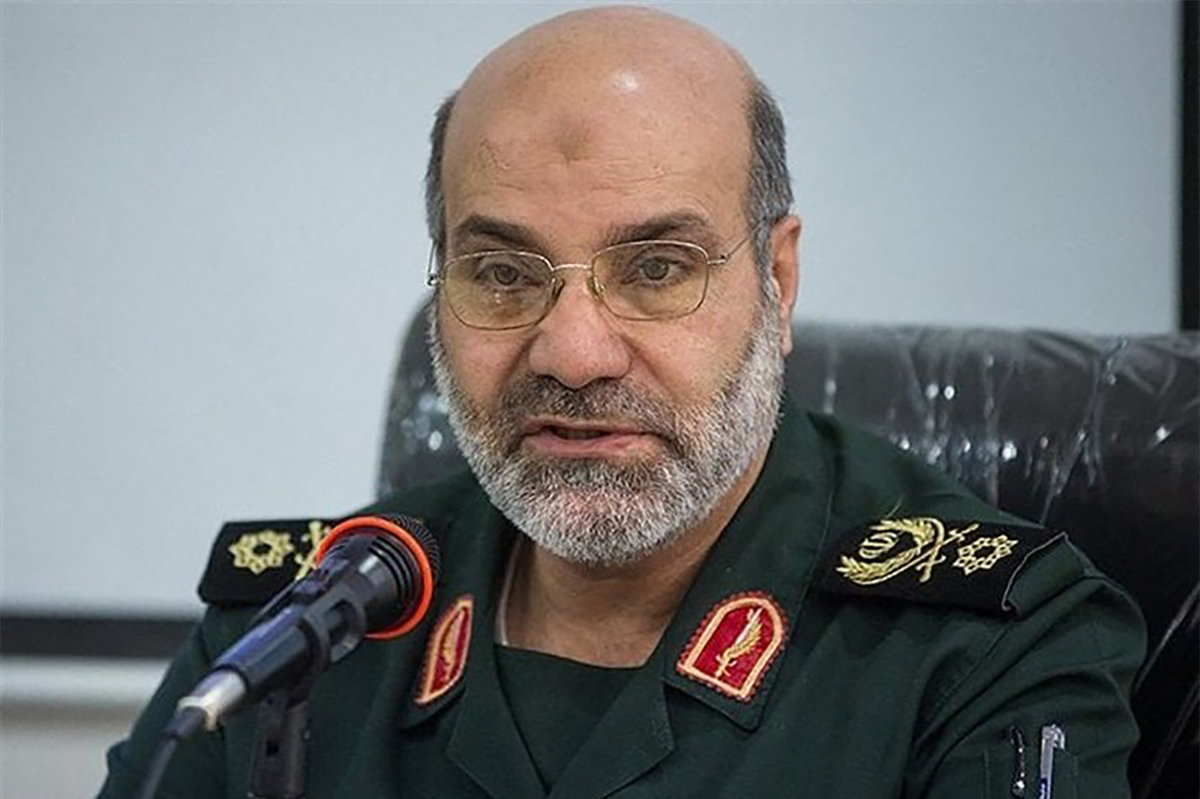

At least 16 people were reportedly killed in the April 1 attack, including two senior commanders of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ extraterritorial Quds Force — Mohammad Reza Zahedi and his deputy Mohammad Hadi Haji Rahimi.

A day after the attack, Iran’s President Ebrahim Raisi promised the strike would “not go unanswered.” Five days later, Yahya Rahim Safavi, senior adviser to Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, warned that Israel’s embassies “are no longer safe.”

Israel has neither confirmed nor denied involvement in the strike, but Pentagon spokeswoman Sabrina Singh said the US has assessed that the Israelis were responsible.

Middle East experts believe Iran’s promised revenge could take many forms, potentially involving direct missile strikes via one of the IRGC’s proxy groups in the region, such as Hezbollah in Lebanon.

“Retaliation seems inevitable. But what form it takes is anyone’s guess,” Ali Vaez, director of the Iran Project at the International Crisis Group, told Arab News.

An attack on an Israeli Embassy “will be on par with what Israel did in Damascus,” said Vaez, but “no one knows for sure what form the Iranian response will take.”

Israel seems to have taken pre-emptive measures. Not only has it bolstered its air defenses and called up reservists, but it also shuttered 28 of its 103 diplomatic missions around the world on Friday, according to the Jerusalem Post, and stepped up security measures around its various consulates and missions.

Stressing that the strike is “unusual,” especially during such “complex and sensitive times,” Eva J. Koulouriotis, a political analyst specializing in the Middle East, believes “Tehran has no choice but to respond.”

She told Arab News: “Tel Aviv, which chose to assassinate Gen. Zahedi and his companions in the Iranian consulate building in Damascus, was able to assassinate him outside the consulate or at the Masnaa crossing on the Syrian-Lebanese border, or even in his office in the southern suburb of Beirut.

“However, the choice of this place by the Israeli leadership, which is also the residence of the Iranian ambassador, is a message of escalation addressed directly to Khamenei and the IRGC.”

Koulouriotis did not discount the possibility of an attack on an Israeli Embassy.

“Last December, an explosion occurred near the Israeli Embassy in New Delhi, without causing any casualties,” she said. “Although no party claimed responsibility for the attack, there is a belief in Israel that Iran had a hand in this bombing.

“Therefore, in my opinion, Tehran will take a similar step in the future without claiming responsibility for the attack, but it will not be a direct response to the attack on the consulate in Damascus due to the sensitivity of this step.”

Notwithstanding, Koulouriotis believes “the Iranian response must be publicly adopted to achieve deterrence on the one hand and to satisfy the popular base of the Iranian regime on the other.

“Therefore, for Tehran to go towards a public and direct attack on an Israeli diplomatic mission in one of the countries of the region will mean a dangerous escalation, not with Israel alone, but with the country in which the attack took place.”

Phillip Smyth, a fellow at the Washington Institute and former researcher with the University of Maryland, believes the statement from Khamenei’s adviser Safavi about Israeli embassies was “certainly a threat,” but “the issue is if Iran or its proxies can deliver on that promise.”

He told Arab News: “Other operations, such as in India and Thailand — both involving Lebanese Hezbollah — failed. There is a lot of intelligence pressure on these types of operations, too.”

Vaez of the International Crisis Group concurs that a response would be “a very difficult needle to thread for Iran.”

He said: “Tehran doesn’t want to fall into an Israeli trap that would justify expanding the war but also can’t afford to allow Israel to target Iranian diplomatic facilities at no cost.”

Smyth, an expert on Iranian proxies, agreed that a conventional direct retaliation, such as using ballistic missiles as its military did before to target US forces and Kurdish sites in Iraq, “could open up the Islamic Republic to more direct strikes by Israel.”

In 2020, Iran responded to the unprecedented US assassination of Quds Force commander Qassem Soleimani at Baghdad Airport with a direct attack on US troops, launching a barrage of ballistic missiles at the Ain Al-Assad base in Iraq.

Since the suspected Israeli attack on the Iranian Embassy annex in Damascus, the US has been on high alert, braced for Iran’s “inevitable” response that could come within the next week, a top US administration official told CNN on April 5.

The US, Israel’s strongest ally, was quick to deny involvement or prior knowledge of the attack and warned Iran not to retaliate against American interests.

“We will not hesitate to defend our personnel and repeat our prior warnings to Iran and its proxies not to take advantage of the situation — again, an attack in which we had no involvement or advanced knowledge — to resume their attacks on US personnel,” Robert Wood, deputy US ambassador to the UN, said in a statement.

US troops in the Middle East, particularly those stationed in Iraq and Syria, have been frequent targets for Iran and its proxies.

Smyth said Tehran might resort to using its “well-developed army of proxy groups spread out across the region,” which include Hezbollah in Lebanon, Kataib Hezbollah in Iraq, militias in Syria, and the Houthis in Yemen.

Hezbollah announced on Friday that it was “fully prepared” to go to war with Israel.

In a speech commemorating Jerusalem Day, the group’s chief, Hassan Nasrallah, described the April 1 strike as a “turning point” and said Iran’s retaliation was “inevitable.”

Middle East analyst Koulouriotis said the most likely first response scenario is that Iran would “give the green light to Hezbollah in Lebanon … to launch a heavy missile strike against a number of cities in northern Israel, the most important of which is Haifa.”

However, “this scenario is complicated and may lead to the opening of an expanded war against Hezbollah that will end with Iran losing the Lebanon card after Hamas in Gaza.”

Tehran might also order its multinational militias in Syria to direct a missile strike against one of Israel’s military bases in the Golan, said Koulouriotis, but this option “is also futile.”

She added: “Moscow may not agree to bring Damascus into a direct conflict with Tel Aviv, which may lead to Assad paying a heavy price, and thus Tehran will have risked the efforts of 14 years of war in Syria.”

As Tehran considers the Damascus embassy annex strike a direct attack “targeting its prestige in the region,” Koulouriotis said it might choose a direct response to Israel using ballistic missiles and suicide drones, “and the Golan region may be suitable for this response.

“Despite the complexities of this scenario linked to the Israeli reaction, which may lead to additional escalation, it saves face for the Iranian regime and sends a message to Tel Aviv that Tehran will not tolerate crossing the red lines.”

Smyth of the Washington Institute believes that while “there may be a (grander) effort to demonstrate a new weapons capability by a proxy or even Iran itself,” Tehran’s response might also take a form similar to the Houthi attacks on shipping in the Red Sea.

“They’ve already demonstrated attempts to economically harm the Israelis by establishing quasi-blockades of the Red Sea by using the Houthis,” he said.

Meanwhile, communities across the Middle East can only wait with mounting concern for the seemingly inevitable Iranian response, mindful that they will likely bear the brunt of any resulting escalation.

Indeed, it is not so much a question of if, but when.

“The delay in response is mainly related to the indirect negotiations between Tehran and Washington,” said Koulouriotis. “To prevent the Iranian response from leading to an expanded war or a more dangerous escalation in the region.”