- ARAB NEWS

- 09 Jul 2025

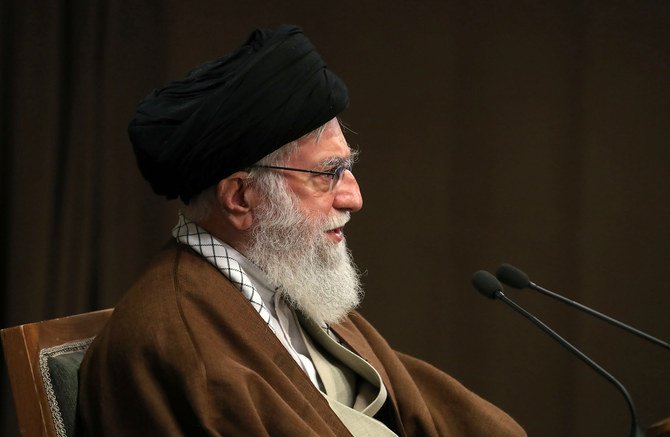

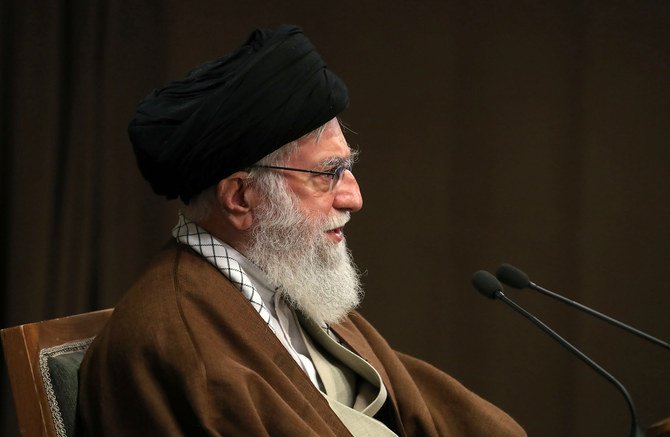

Ayatollah Ali Khamenei is like a hunter who shoots animals for the purpose of stuffing them and nailing them to his wall. Today Beirut, Damascus, Sanaa and Baghdad are the dying trophies on display above Khamenei’s fireplace.

Khamenei may brag that he has severed these heads from the bleeding corpse of the Arab world, but Tehran is incapable of causing these states to prosper and flourish under its hegemony. Some finance ministers have the “Midas touch” in stimulating economic growth. Some gardeners have “green fingers” in making flowerbeds explode with color. Everything Tehran touches dies.

Iraq, Lebanon and Syria have endured periods of turbulence, but for much of their proud history they enjoyed prosperity and cultural florescence, with world-class education systems and a rich heritage lending itself to tourism — showcasing the Arab world at its best.

Under Iranian tutelage these nations rapidly unraveled into impoverished, marginalized and backward basket cases where humiliated citizens will struggle even to feed themselves in the coming months. First the middle classes were decimated; then there was no work for the working classes; now even bloated state sectors have ceased paying their coddled and corrupted civil servants. Lebanese Druze leader Walid Jumblatt warns of the impending “hunger revolt,” with nation states disintegrating as “every chief of tribe, every chief of community is trying to satisfy his own people.”

Iraq’s GDP is projected to contract by 5 percent in 2020, requiring an estimated $40 billion injection of foreign cash to remain afloat. Lebanon’s economy is expected to shrink by at least 12 percent this year, meaning that its current $90 billion debt burden will continue to escalate beyond its current world-beating level of 170 percent of GDP. Iran’s GDP has declined by about 10 percent over the past year. Official unemployment statistics soared to 26 percent (the actual level is certainly much higher). The economies of Yemen and Syria are in such a woeful state as to defy meaningful statistical representation.

Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah scorns IMF bailouts and foreign aid. Instead, he sees these “resistance” states thriving as an economic bloc: Lebanon’s financial woes will be alleviated by opening its doors wide to Syria and the “vast” markets of Baghdad. In reality, these miserable states are each poorer than one another. Nasrallah’s vision means slamming Lebanon’s doors to the wider world. He proclaims Lebanon and Syria’s Arab identity, while shutting them off from the wealthier Arab states that could offer a genuine economic renaissance.

Iran’s proxies once enjoyed a modicum of support, notably within Shiite communities. But corruption, economic collapse, criminality and global marginalization have erased any figleaf of popular legitimacy; meaning that, just as in Syria, Tehran must resort to naked coercion to retain its Arab colonies. I suspect even Nasrallah now realizes that his rhetoric about liberating Palestine and “next year we’ll be praying in Jerusalem” nowadays mostly provokes laughter. The millions of protesters recently marching throughout Lebanon and Iraq offer a foretaste of the turbulence to come.

Arab states should take the lead in helping victims of theocratic colonialism extract themselves from Tehran’s grip, demonstrating what is on offer if long-suffering client states rediscover their Arab identity and plug their economies back into global financial and trading networks.

Baria Alamuddin

Through superficial demonstrations of flexibility, Tehran’s puppets are frantically buying time at a moment when the crippled Islamic regime is weaker than it has ever been: European leaders behave with shocking intellectual dishonesty in touting prospects of IMF bailouts, knowing there is no possibility of the radical institutional reforms required to roll back the clientelistic, kleptocratic governing model upon which Hezbollah and its cronies thrive. An impotent Prime Minister Mustafa Al-Kadhimi tells everybody what they want to hear, guaranteeing that weapons will be monopolized by the Iraqi state, while hailing Al-Hashd Al-Shaabi’s “essential” role. Such glaring contradictions can be ignored only for so long.

Israel is trying to declare victory in its air campaign against Iran-aligned targets through spurious claims of Iranian withdrawals from Syrian soil. There is some evidence of Iran redeploying its assets to reduce exposure and costs, while making increased use of local militias and foreign fighters. Khamenei would rather lose control of Mashhad and Shiraz before loosening his grip on Damascus and Baghdad.

Donald Trump lacks the vision or courage of his convictions to capitalize on the successes of his own policies; notably his “maximum pressure” strategy, which in tandem with COVID-19, collapsing oil prices and other factors has dragged Iran to the brink of financial ruin. Even Joe Biden’s foreign policy advisor, Jake Sullivan, recently acknowledged that Trump’s “sanctions have been very effective.”

A genuinely audacious diplomatic strategy would seize this opportunity to radically cut Iran down to size across the region. Trump prefers to avoid any pre-election boat-rocking, but whoever is in the White House in 2021 will have Iranian militancy, terrorism and nuclear proliferation at the top of their in-tray.

After neglecting Lebanese politics for three years, there are indications that US efforts to pull Gebran Bassil away from Hezbollah’s embrace are bearing fruit. Nevertheless, Trump’s strategic confusion is evidenced by the dithering over how to react to the sanctions-busting flotilla of Iranian ships transferring fuel to Venezuela.

Why are there no attempts to seek common ground with Vladimir Putin, who has soured against his erstwhile allies in Damascus and Tehran? Whether Washington likes it or not, Moscow is now a Middle East power. Why not exploit this in a combined effort to expel Iran, particularly given the warm ties that Russia and America jointly enjoy with both Israel and the GCC states?

We mistake Iran’s weaknesses for strengths. This farcical regime limps from one day to the next and, even when it showcases military exercises and missile prowess, it ends up slaughtering its own soldiers in friendly-fire debacles or blowing up civilian aircraft.

It often feels as if Khamenei will live forever (just to spite us), yet the question of his successor is unresolved. Iranians will be reluctant to accept the hated hard-liners whose names have been circulated, and an attempt by the Revolutionary Guards to impose their own formula risks triggering civil disorder. If the regime falls, Hezbollah, the Hashd, the Houthis, and all Tehran’s other mercenaries will be scattered like origami models in a hurricane.

Arab states should take the lead in helping victims of theocratic colonialism extract themselves from Tehran’s grip, demonstrating what is on offer if long-suffering client states rediscover their Arab identity and plug their economies back into global financial and trading networks.

Unfortunately, it will probably fall to historians to lament that this moment of maximum Iranian weakness coincided with a period when the international community lacked the foresight and courage to resuscitate these moribund states with a financial and political kiss of life. All the while, Tehran’s kiss of death leaves a relentless trail of anarchy and failed states in its wake.