- ARAB NEWS

- 02 Jul 2025

The US has recently taken two decisive steps that could change the course of events in the region and bring Iran to the negotiating table. On Dec. 29, it attacked several facilities in Iraq and Syria belonging to Kata’ib Hezbollah, the group that had previously sent a barrage of rockets into a Kirkuk military base housing US, Iraqi and coalition forces, killing an American contractor and injuring several troops. Then, on Friday, a US drone killed Qassem Soleimani, the head of the Quds Force and mastermind of Iran’s regional activities.

Those two major developments were surprising because they came after months of American restraint in responding to Iran’s provocations. They were also remarkable because they were unusually robust and daring in confronting Iran directly.

This kind of action was needed to disabuse Iran of the notion that there were no consequences for its brazen attacks on international shipping and oil facilities, and its belief that it could shape the future of Iraq, Syria, Lebanon and Yemen at will and with maximum violence when needed.

But, to be effective, the US military pressure has to be sustained in case Iran responds with force. In addition, military pressure has to be accompanied by economic pressure and diplomacy. It is an axiom of foreign policy that diplomatic efforts not backed by credible pressure are ineffective, and it is equally true that military success can produce the desired results only when combined with diplomacy, which can translate it into political advantage.

Degrading Kata’ib Hezbollah and eliminating Soleimani are good examples of pressure that could work, if combined with diplomacy. They also have to be seen as being part of a long-term strategy with clear goals, and not just random or isolated events in reaction to a particular provocation, such as the death of the American contractor in Kirkuk.

With Soleimani out of the way, the more radical elements that he represented could be weakened.

Abdel Aziz Aluwaisheg

Negotiations are the only sustainable option to resolve the standoff between Iran and the US (in addition to Gulf partners and indeed the rest of the world). Ironically, Iran may be more willing to sit at the table as a result of the US’ robust reactions in Iraq. Iran escalated for years, especially during 2019, with little pushback from the US or anybody else. As such, it had no incentive to negotiate and nothing to lose by being belligerent and unresponsive to calls for negotiations.

With this kind of response from the US, if sustained, Iran may see the value of negotiating instead of bludgeoning its way through the region. Appeasement and turning a blind eye failed to curb Iran’s appetite for regional adventurism, epitomized by Soleimani’s brazen actions.

Some observers have noted the outpouring of support for Soleimani after his death and conclude that Iran is only interested in taking revenge against the US or its Gulf partners. However, much of that support for Soleimani is orchestrated and could be turned off by the regime if it wanted. Momentary bluster over his death should not be confused with the regime’s long-term interests. Despite staged mourning processions, the general was an embarrassment to many reasonable Iranians, including some moderate leaders.

For many others, Soleimani was instrumental in the violent suppression of peaceful dissent at home and a warmonger abroad. He was a designated terrorist and an unindicted war criminal in light of the atrocities he masterminded in Syria and elsewhere. Obviously, those opposed to Soleimani in Iran could not express their views or stage demonstrations to show their feelings toward him. With Soleimani out of the way, the more radical elements that he represented could be weakened.

Other observers take the vote on Sunday by the Iraqi Parliament as another sign that the US’ actions have backfired and made negotiations even harder to start. But the vote was largely symbolic. The Parliament merely asked the government to “seek” to end the presence of foreign forces in Iraq, without specifying which forces. It was clear from the remarks of Prime Minister Adel Abdel Mahdi before the assembly that he was also sending a message to Iran-supported militias when he said that the Iraqi state has the exclusive right to possess and use arms and that, if a group wants to play a political role, it has to give up its weapons. Thus the Parliament’s vote should not be taken as binding legislation but as an expression of frustration. There was limited support for that vote in any case, as important political blocs had boycotted the session.

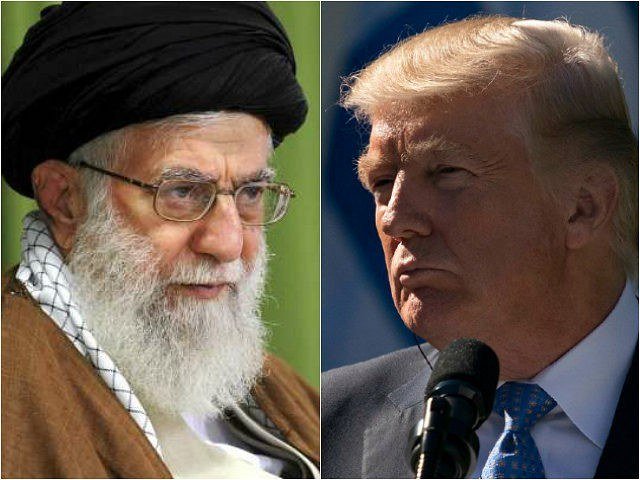

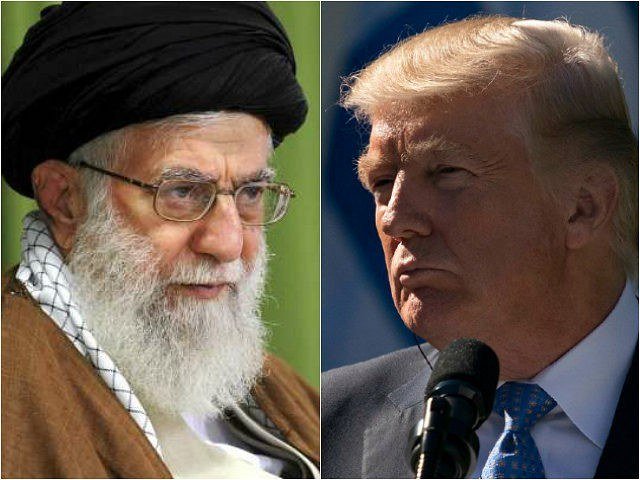

The sentiment in both Iran and Iraq should not then preclude negotiations, which US President Donald Trump has called for repeatedly in the past but Iranian leaders have rejected. It is true that Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei has refused dialogue with the US and he repeated that rejection after Soleimani’s death. However, what is needed is negotiations focused on a specific issue, according to commonly shared guiding principles, not an open-ended dialogue. The negotiations do not have to be with the US alone, but with multiple parties.

In its correspondence with Iran, the Gulf Cooperation Council has articulated those guiding principles, emphasizing adherence to the UN Charter, which means respect for national borders, political independence and the territorial integrity of neighboring states, as well as non-interference in their internal affairs. Those principles also include refraining from using force or sectarian strife to achieve political goals.

To advance this ambitious goal of political negotiations over the issues that preoccupy Iran’s neighbors, the US has to stay the course of maximum pressure, while combining it with diplomacy that has clear goals and payoffs for good behavior. To get popular support for the administration’s aims, diplomacy has to start at home, despite the difficulties of the political season. US allies and partners, some of whom are still skeptical, also have to be engaged and asked to support a negotiation process with Iran.