- ARAB NEWS

- 12 Jul 2025

Sir John Jenkins

The conflict, sparked by the Iranian Revolution, led to two Gulf wars

Summary

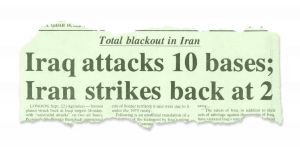

On Sept. 22, 1980, Iraqi aircraft bombed 10 air bases in Iran, launching a brutal war that would drag on for eight years.

The immediate trigger for the war was Saddam Hussein’s fear that the 1979 Iranian Revolution would be exported to Iraq and the other Gulf states. The two countries also had a long history of conflict over control of the Shatt Al-Arab waterway and Saddam hoped to seize the oil-rich Iranian province of Khuzestan.

In 1981, the land war escalated into what became known as the Tanker War when Iraq began attacking ships bound to or from Iranian ports. Iran reciprocated, attacking oil tankers from neutral countries and leading the US Navy to introduce a convoy system to protect shipping in the Gulf.

By the time the conflict ended in stalemate and a UN-brokered peace deal in 1988, it had cost the lives of up to 1 million people. As one commentator wrote, “few wars in modern history had done less to further the ambitions of the leaders that started them at so high a cost to their peoples.”

LONDON: I joined the UK’s Foreign and Commonwealth Office in September 1980, two weeks before Iraq invaded Iran and started the bloodiest war in modern Middle Eastern history. Perhaps a million combatants and uncounted civilians died. Four decades later, we still live with the consequences.

Following anti-government riots inspired by Iran’s Islamic Revolution, Iraq demands Iran withdraws its ambassador.

Iraq executes Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Baqir Al-Sadr, a supporter of Iran’s Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, and his sister.

Iraqi militants linked to Iran assassinate a number of Saddam Hussein’s Ba’ath Party officials.

Saddam announces Iraq is withdrawing from the 1975 Algiers Accord, under which Iraq and Iran agreed to resolve their border disputes.

Iraqi air force bombs Iranian airfields.

Iraqi troops cross the border into Iran.

US frigate the USS Samuel B. Roberts hits a mine laid by Iran in the Gulf.

The US warship USS Vincennes accidentally shoots down an Iranian airliner, killing all 290 people on board.

Iran accepts UN Security Council Resolution 598, which calls for an end to the fighting and a return to pre-war borders, and requests a cease-fire.

Under pressure from the UN, US and Arab allies such as Saudi Arabia, Iraq finally agrees to cease-fire.

Resolution 598 comes into effect, ending the war.

Iran-Iraq peace talks begin.

The UN peacekeeping force sent to monitor the cease-fire in August 1988 finally withdraws.

There had always been tensions between the two countries. But 1979 had really set the scene. That was the year that changed everything. The shah was overthrown, Juhayman Al-Otaibi seized Makkah’s Grand Mosque, Zia-ul-Haq executed Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, an Islamist insurgency in Syria accelerated, and the Soviets invaded Afghanistan. These events ushered in a new and alarming era of turbulence and instability.

For the Middle East, the subsequent outbreak of hostilities between Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and revolutionary Iran became the defining event of the period. It represented a clash between two competing versions of modernity: The Baathist dream of mystical Arab nationalism and Ruhollah Khomeini’s heterodox reimagining of Islamism, based on a mythical past and deriving legitimacy from a reactionary interpretation of clerical authority. Both systems were harshly repressive. And each had their true believers.

Iraq thought itself to be stronger, especially after the revolutionaries in Iran had purged the generals and Tehran’s traditional sources of military supply in the West dried up. But Iran, surfing a wave of popular enthusiasm, proved more resilient than expected. The war became an attritional stalemate. Khomeini refused all appeals to bring the conflict to an end until he was finally forced to do so in 1988, after horrifying losses on both sides.

For much of this period I had a ringside seat as a young diplomat in Abu Dhabi. The impact on the Arab states of the Gulf was huge. They feared the expansion of the Iranian revolution into their territories. Article 154 of the new Iranian Constitution had committed Iran to exactly this. And it had been put into effect partly through the activities of an organization linked to Ayatollah Hussein-Ali Montazeri and partly through support channeled through what became Lebanese Hezbollah to dissident Shiite movements in Kuwait, Bahrain and Saudi Arabia in particular — whose activities included bombings and plane hijackings. This was the most serious challenge to their stability and cohesion that these states, most of which had only achieved independence between 1961 and 1971, had ever faced. Their domestic institutions and military capacities were still weak. And Iran represented both a material and an ideological threat. It is hardly surprising that they chose to financially support Iraq, which was Arab, Sunni-ruled, populous, educated and a familiar (if sometimes overbearing) neighbor.

The end of the war in 1988 left Iraq with massive debts to other Gulf states, particularly Kuwait, and widespread damage to essential infrastructure, particularly in the south, around Basra, where most of Iraq’s oil fields are concentrated. Saddam decided to recoup his losses by bullying Kuwait, which refused to buckle. That led him to invade on Aug. 2, 1990. He may have thought he could do a deal that would have left him in control of Kuwait’s northern oil fields. Instead, he suffered a catastrophic defeat that left his military aspirations in tatters, his weapons programs subject to international supervision and the economy crippled by sanctions, which tore apart the fabric of Iraqi society. The uprisings that followed in the Shiite south and the Kurdish north — neither successful in a conventional sense — helped set the scene for the way in which Iraq reconstituted itself along sectarian and ethnic lines after Saddam’s eventual fall in 2003.

“Only a few weeks ago, observers were wondering whether Iraq and Iran would soon be fighting a border war. Today, with this question answered, another one arises: Will such a war remain a limited one, or will it grow into an all-out conflict?”

From an editorial in Arab News on Sept. 23, 1980

In Iran, the myth of the war as one of exemplary national resistance at a time of isolation has endured powerfully, at least within the ranks of the regime and its supporters. It has fed a narrative of victimization that already had deep historic and cultural resonance among many Shiites. It also led Iran to double down on a strategy of so-called mosaic defense and proxy warfare, designed to compensate for conventional military weakness. It does not in any way seem to have reduced Tehran’s appetite for destroying Israel and ultimately bringing its neighbors under Islamist rule.

And this is the context within which Saudi Arabia operates today. The war had a direct impact on the Kingdom, as the US and other Western forces mobilized on Saudi soil to confront the invasion. It was this that led elements of the so-called Sahwa to confront the government and set Osama bin Laden irrevocably on the path to 9/11. In Kuwait, pressure built for a restoration of the prorogued National Assembly in the name of democracy. In practice, this gave various tribal and religious groups a stick with which to beat the government. This has complicated Kuwaiti politics ever since.

These complications remain. The overthrow of Saddam in 2003 was widely seen as a belated sequel to 1991, when coalition forces had failed to follow the fleeing Iraqi army all the way to Baghdad and had instead allowed Saddam and his loyalists to regain domestic control outside the Kurdish areas. The diplomatic maneuvering of the subsequent decade corrupted parts of the international system, with the oil-for-food scandal and persistent obstructionism by certain members of the UN Security Council. But 2003 was, in practice, a victory for Iran — as was the overthrow of the Taliban in 2001.

And this story isn’t over. The Taliban is back, Iraq remains in turmoil, and Iran itself is now perhaps coming up against the limits of its own competence both domestically — where its responses to the shooting down of an airliner and now to coronavirus have been scandalously mishandled — and externally, where the consequences of overextension in Syria and Iraq may now be starting to appear.

Iran, surfing a wave of popular enthusiasm, proved more resilient than expected

Sir John Jenkins

If Khomeini had not been expelled from Najaf in 1978; if the shah had not had cancer; if Saddam had reacted more calmly to Iranian provocations in 1979; if Khomeini had agreed to a cease-fire after the recapture of Khorramshahr; if Saddam had not then gambled on an invasion of Kuwait; if Iran had become a more normal country, then we should be living in a different world. But we’re not. More’s the pity.