- ARAB NEWS

- 18 Jul 2025

Climate events with catastrophic consequences are on the rise; wildfires causing loss of life and property in California and Australia, hurricanes in the Atlantic, super typhoons in the Pacific, drought in vast stretches of Africa.

Insurance companies who have to pick up the tab for this destruction are increasingly selective about which industries they are willing to insure or invest in. Coal is out, and oil and gas are on the watch list. International operators such as the European Investment Bank have already ruled out financing hydrocarbons.

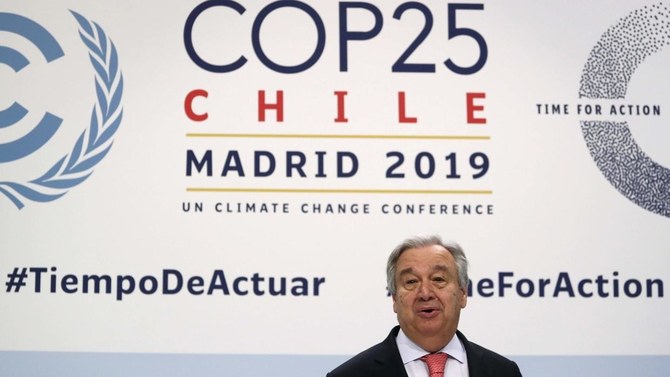

The UN’s climate change conference in Madrid failed to find consensus, showing how difficult it is to come to framework agreements for carbon pricing when the world’s largest economy is not on board; in 2018 Donald Trump announced that he would leave the Paris Accord on climate change.

No wonder, then, that the young, and the parents who sympathize with their agenda, are concerned about climate inaction. The 17-year-old Swedish activist Greta Thunberg has inspired millions of young people to follow her path and strike on behalf of the environment rather than attend school on Fridays. Last year, the Extinction Rebellion movement paralyzed several big cities.

They are bringing this issue to the ballot box. At recent elections in Europe, the green agenda topped most other concerns. A wave of green representatives swept into parliaments in Switzerland, Austria and Sweden, and did well in regional elections. The big established parties were quick to pick up the green mantle; the image ingrained in collective memory has to be that of Markus Soder, arch-conservative leader of the Bavarian Christian Socialist Union, hugging a tree. He is making hay with his new green agenda, and the chancellorship itself seems no longer out of reach. New European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen made waves with her “Green Deal” to make Europe the first emissions-neutral continent by 2050.

It was therefore no surprise when Sebastian Kurz chose the Green Party under Werner Kogler as his coalition partner after winning Austrian parliamentary elections in September, and will now be chancellor once more.

The UN’s climate change conference in Madrid failed to find consensus, showing how difficult it is to come to framework agreements for carbon pricing when the world’s largest economy is not on board.

Cornelia Meyer

The two parties’ agendas seem far apart. Kurz’s Austrian People’s Party (OVP) stands for a strict immigration regime, a pro-business agenda and conservative values. The Greens lean more to the left; their key topics are climate change, environmental protection and social justice.

The OVP is clearly the senior coalition partner, with 10 out of 13 ministries. Nevertheless, the new government’s agenda includes a climate-change package that aims to make Austria emission neutral by 2040 — 10 years before the EU, or indeed the UK. Public transport will go electric, and there will be moderate taxes on air travel and an as yet unspecified climate tax on industry — although the business agenda is in large parts influenced by the OVP’s policies. In return, the Greens obtained a newly created super ministry for transport, environment, energy, technology and innovation, which will be led by former environmental activist Leonore Gewessler. The OVP’s agenda also won on the immigration agenda; the new government will adhere to the ban on hijabs in schools for girls under 14, which parliament passed in May 2019. As a concession, the Greens have an integration ministry. While this conservative green coalition may surprise, and its climate change package still has holes and inconsistencies, it has precursors at the regional level; the same coalition has been running Tirol since 2013 and Vorarlberg since 2014.

In Germany, too, an alliance between green and black is no longer counterintuitive. The demography of the Greens has changed since the 1990s and early 2000s, when they were first in federal government under Social Democrat Chancellor Gerhard Schroder. More and more affluent, socially concerned Germans — the “latte macchiato class” — lean toward the Green Party and its agenda, in line with what concerns their teenage children. The slow demise of the Social Democrats and their drift to the left frees up a whole new tranche of the electorate, and the Green Party seems to be the beneficiary.

The environment has become mainstream, in Europe in particular. It is not just the young but also insurance companies and other parts of industry who are jumping on the bandwagon — not just out of concern over climate change, but out of cold economic calculation. The pendulum has swung toward the Greens. Expect it to remain there for the next few years.