- ARAB NEWS

- 11 Jul 2025

Donald Trump reaffirmed this week that US-China negotiators are in the “final throes” of a phase one trade deal. Yet, while financial markets have been buoyed by the mounting signals of an agreement, this is still by no means in the bag, especially with bilateral differences over Hong Kong potentially upsetting the applecart.

Optimism has risen recently not just with Trump’s comments, but also the fact that China’s annual Economic Work Conference is expected to convene in December — some commentators suggest this is a further sign that a deal is imminent. There are reasons for both sides wanting to move ahead before Christmas: Trump would have a deal to try to crow about as he enters election year, while China wants to demonstrate economic stability amid the continued political unrest in Hong Kong and a flurry of sub-par national economic data.

A further incentive to move before Christmas is that the next tariff deadline falls on Dec. 15, after which additional US levies on Chinese imports are scheduled. This would see a 15 percent rate applied to a further $160 billion-worth of Chinese goods.

However, while the outline of a deal — which would reportedly roll back tariffs — seems to be in place, resolving this by 2020 is by no means certain, as the oscillations of the last year show. Take the example of the spring, when a deal had seemed imminent. In March, Trump asserted that US-China talks were going “very well” and that “probably one way or the other we’re going to know over the next three to four weeks.” It was reported then that both sides were poring over a 150-page draft document that the president said would be a “great” agreement.

Then, like now, there seemed to be incentives to cut a deal, including the release of the Mueller report’s conclusions, which were perceived in many world capitals to have placed Trump in a stronger domestic political position. In this context, the president’s prospects of winning a second term were widely seen in Beijing to have risen, thereby providing greater reason for Chinese policymakers to double down in the trade negotiations.

Part of the reason why a delay (or breakdown) of the stage one talks cannot be entirely ruled out lies with bilateral differences over Hong Kong. On Wednesday, Trump signed the Hong Kong Human Rights and Democracy Act, which had been approved by Congress. This legislation, which has infuriated Beijing as an “intervention” in its affairs, requires an annual check on whether Hong Kong has sufficient political autonomy from Beijing to quality for the continued special US trading consideration that enhances its status as a world financial center.

Another factor adding uncertainty is the ever-mercurial Trump and his (potentially fast-changing) perceptions of his political interests in 2020 in the context of seeking to fulfill his promise to “Make America Great Again.” This program includes seeking to reduce the US global trade deficit and cracking down on trade practices perceived to be unfair.

Trump has long had Beijing squarely in his sights here. For instance, he signed legislation last year requiring the US commerce secretary to deliver a “Report on Chinese Investment” in the US to Congress and the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States every two years up to 2026.

This sentiment underlines that, even if a stage one deal is signed in December or in 2020, tensions will by no means disappear and still have the potential to severely disrupt what is probably the world’s most important economic and political bilateral relationship. Should talks break down again, despite the presently positive mood music, Beijing will know there remains the possibility that Trump’s hostile rhetoric will return if he judges it will help his re-election.

Economically, he has previously slated China for alleged misdemeanors, including currency manipulation. Outside of the economic realm, it is clear he genuinely believes China represents the primary threat to US interests globally. Here a string of security issues still cloud the bilateral agenda, including in the South China Sea, where Washington has clashed with Beijing over its new, artificial islands.

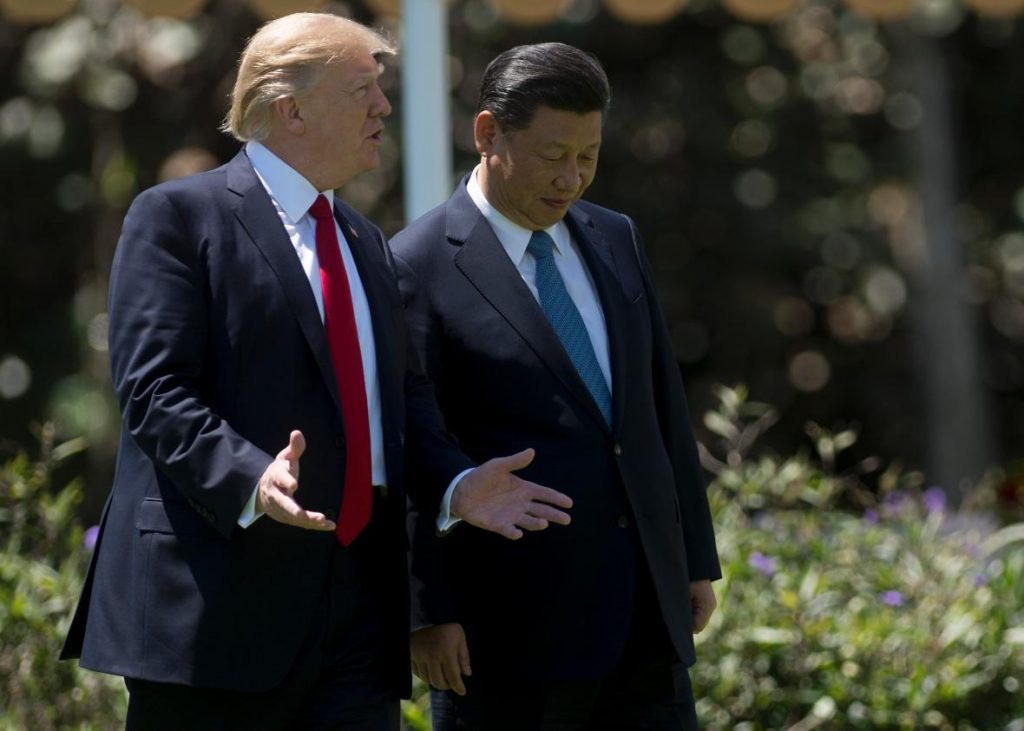

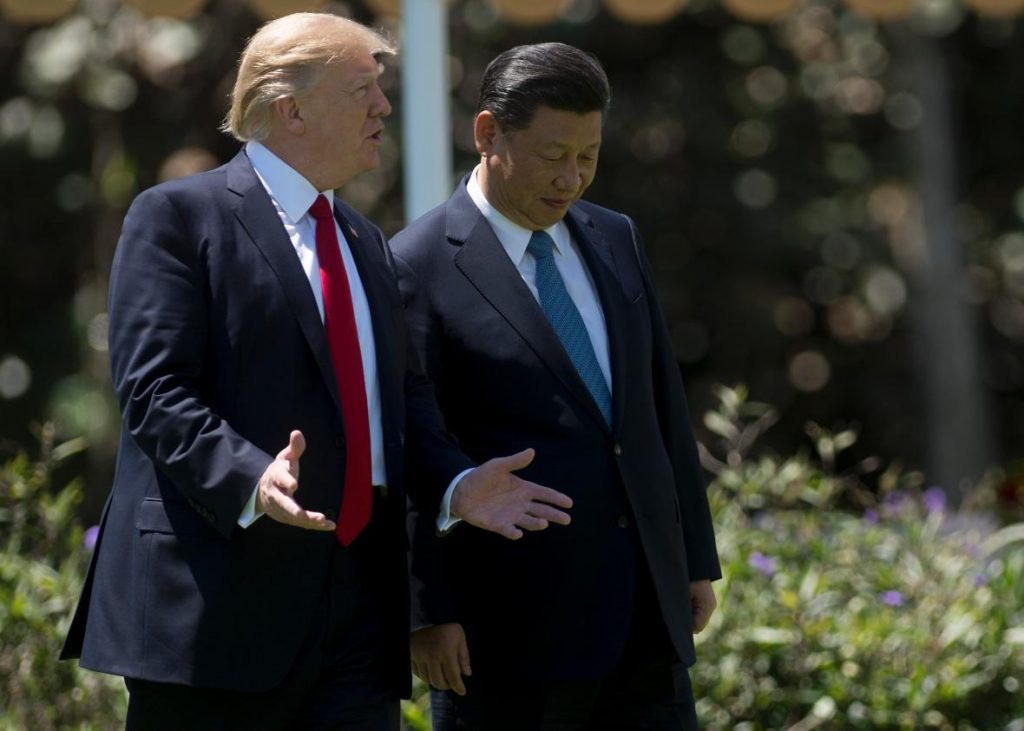

Ultimately, Trump needs to show his US political base key concessions from Beijing on these issues in order to fulfill his “America First” agenda. Here he has previously asserted that “everything is under negotiation” and what he ideally favors — building on the recent diplomacy with Xi Jinping over North Korea — is a wider grand bargain extending beyond the economic arena, where one of his key asks is to see the Chinese currency floated, to other security issues.

While such any such grand bargain is a long way off, and may indeed never happen, even a stage one trade deal could provide greater overall stability in the global economy and limit damage to the currently creaking international trade system. An agreement of this kind may also have a broader positive effect on international relations, possibly helping to underpin a renewed basis for bilateral relations into the 2020s.